Belgium may be small, but it thinks big when it comes to dogs. Few countries roll out the welcome mat for four-legged companions quite like this one.

In Brussels cafés, the waiter will often bring water for your dog before taking your own order. Trains and trams are canine friendly. Even the army is obsessed: its elite units are more likely to boast about their Malinois dogs than their machine guns.

From pampered pets in city apartments to parachute-jumping shepherds strapped to Special Forces handlers, dogs are stitched into the fabric of Belgian life. They are not just companions – they are colleagues, athletes, guardians and, occasionally, national celebrities.

Take the Belgian shepherds. While other countries may content themselves with perfecting a single breed, the Belgians went for four (not including the Bouvier de Flanders, a more ancient sheepdog – see separate article).

In 1891, the Royal School of Veterinary Medicine in Anderlecht decided to outdo their German and British peers by engineering a quartet of shepherd dogs, differentiated mainly by coat length and colour but united by their brainpower and athleticism.

Belgian Shepherd

The Malinois quickly became the star pupil — a sleek, short-haired dynamo with the fawn coat and black mask that have since become synonymous with intelligence, stamina and, occasionally, danger. If James Bond were reincarnated as a dog, he’d probably be a Malinois.

His siblings are no less distinguished. The luxuriant black Groenendael was bred in aristocratic surroundings by Nicolas Rose, owner of the Groenendael chateau, a former abbey. He began selectively breeding this beautiful black-coated, long-haired variety of Belgian shepherd using two foundation dogs – a male called Picard d’Uccle and, ironically for such a large breed, a female called Petite.

The proud fawn-and-black Tervuren was born of a cross-forest romance by a Mr Corbeel from the Brussels suburb. He owned a fawn-coloured dog named Tom, who he bred with a black shepherd named Poes, producing puppies with the now-iconic long fawn coat and black mane.

And the scruffier Laekenois, the rebel cousin with the wiry coat, more often seen patrolling royal estates than red carpets. The fourth and rarest of the Belgian shepherds, its shaggy, rough, fawn-coloured coat sets it apart from its cousins, and is used by actual human shepherds and gamekeepers, including those working on the royal estates of Laeken.

Soldier dogs

Of course, Belgian shepherds were originally bred to boss sheep. But as sheep herding dwindled, these versatile hounds found new careers: guarding, sniffing out contraband and generally making life difficult for wrongdoers. By the early 20th century, most shepherds were re-purposed to serve as guard dogs as well as police and army detection dogs.

The Malinois, in particular, has become a global export — a canine super-soldier coveted by armies, customs officers and police forces everywhere from Kabul to California. The US Navy SEALs had one at their side on the 2011 mission that killed Osama bin Laden (he was called Cairo). Belgium, it turns out, produces not just the world’s best chocolate and beer but also the hardest-working dogs on the planet.

Belgian Shepherd searching ruins

Shepherd dogs guard sheep or drive sheep – and some can even do both. “They are brave, obedient, easy to train and strong physically. They make excellent guard and detection dogs,” says the commanding officer of the Belgian military working dog unit, Yves Mommens.

That’s why they are the first-choice breed across all branches of the Belgian military. “We have springer spaniels and Labradors working as detection dogs. And German shepherds are used as guard dogs. But 90% of our dogs are Malinois,” Mommens says.

The army buys dogs at age two from trusted breeders from around Europe for between €2,000 and €5,000. Once the dog has passed its physical and character tests, it goes on a two-week quarantine, as a further precaution.

Then, once it has the all-clear, the dog is paired with a handler. The two train together: three months for a guard dog, six for a detection dog. Then they - handler and dog - are ready for work and a one-on-one relationship that will last for the rest of the dog’s life.

Dogs selected for the Special Forces branch of the Belgian military receive extra training for parachute jumping. Incredibly, these dogs willingly jump out of aeroplanes, strapped to the chest of their handler.

Malinois were used by the Belgian military as guard dogs in Afghanistan between 2004 and 2016 when the army oversaw security at Kabul airport – although none are on active duty overseas with the Belgian military at the moment. “We do have a star, a detection dog called Flaco,” Mommens says. In March 2016, he was one of two dogs sent to Zaventem airport in the wake of the terrorist attack there, to check for further explosive devices.

“He did a sweep of the airport,” Mommens says. “He suffered from what he inhaled that day and died some months later. We have a memorial for the dogs like Flaco that died in service.” However, the army doesn’t hand out medals to its four-legged comrades.

Military dogs get a day off each week, and they go home with the handler and live as a pet with his or her family. “Working dogs retire at age eight – so that’s six years active service,” Mommens says. The average life of a Malinois is between 12 and 15 years.

“They live with their handler’s family after retirement for the rest of their lives, so most handlers have more than one dog at home at once,” he says. The army pays for all food and vet costs until the dog passes away.

Avoiding inbreeding

The issue of inbreeding divides breeders. Some say it is the only way to be sure of what you’re getting, while others will travel great distances precisely to avoid the risk of there being a family link between dog and bitch.

Johan Weckhuyzen, a trainer, breeder and the founder and chairman of the World Federation of Belgian Shepherds (Féderation Mondial des Bergers Belges), distinguishes between in- and line breeding. Inbreeding is the mating of individuals that are closely related — brother, sister, parent or grandparent. Line breeding is a milder form of inbreeding, where breeders deliberately mate animals that share a common ancestor — often a well-regarded prize-winning animal — but avoid the very closest relations.

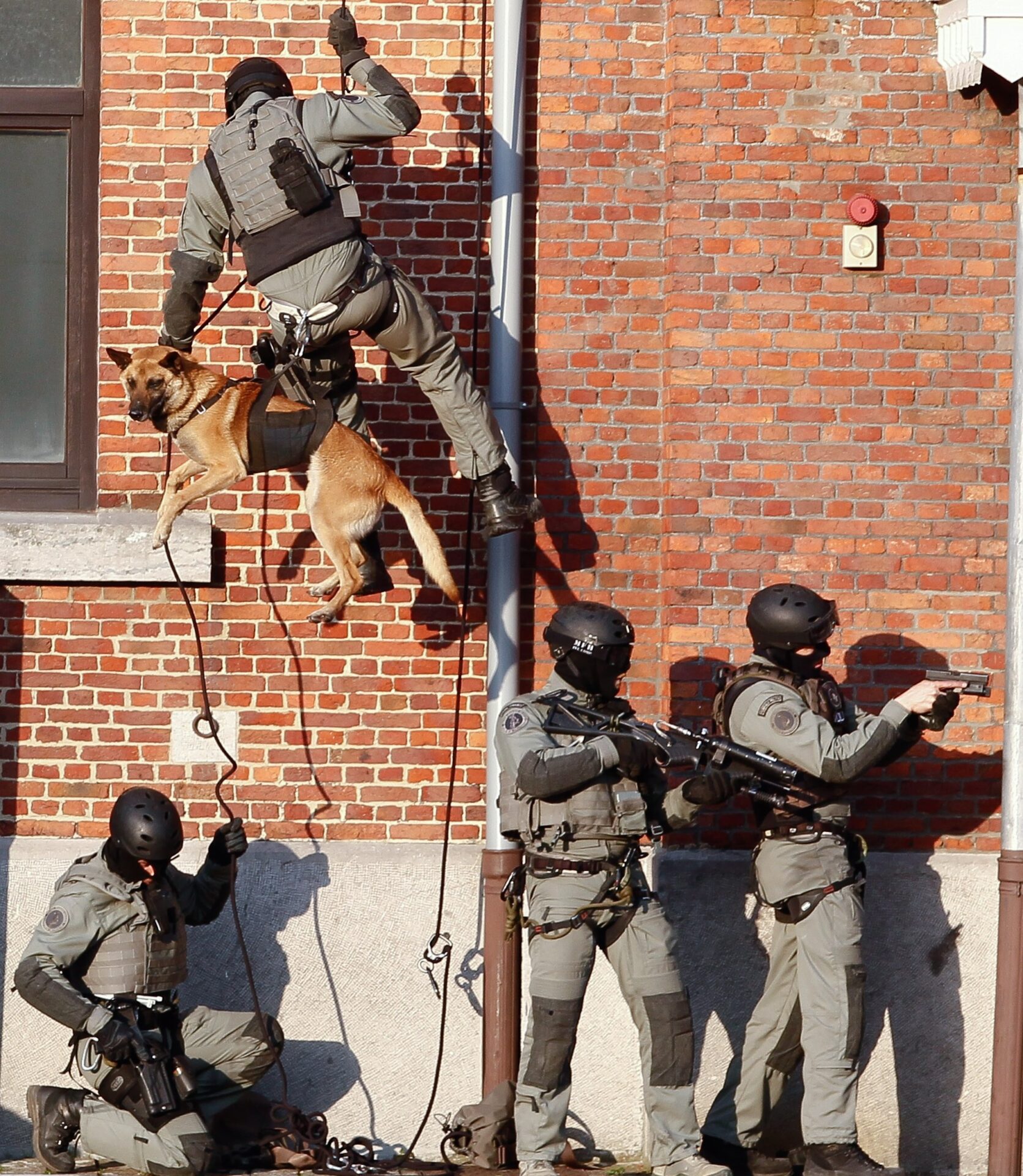

Illustration picture shows police officers and a Belgian Shepherd hanging from a line, during the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Special Forces division of the Federal Police (CGSU), in Brussels, Thursday 22 March 2012. Credit: Belga / Bruno Fahy

“There are two motives – money and perfection,” Weckhuyzen says. “Line breeding is important, especially with working dogs because you want to know what the dog will be like. The biggest challenge with breeding dogs is knowing what’s going on in their heads. You can’t take chances. If you know the genetics of the bloodline, you are more sure what the dog will be like,” he argues.

And to create one of the four Belgian shepherd dogs, you have to inbreed. The Malinois breed, for example, can trace its origins back to two males, Dewet and Tjop, who were paired with both their daughters and their granddaughters. “It’s how the breed emerged,” Weckhuyzen says.

Belgium legislates against excessive inbreeding, and breed clubs also play a key role in setting and maintaining standards that discourage harmful inbreeding. “I travelled to Germany for a mate in order to avoid a related line,” says Maja Zaluska, a breeder of the rarer wiry-haired Laekenois breed. She lives outside Stockholm, Sweden. Being rarer, the breed is potentially more at risk of accidental inbreeding.

She agrees that inbreeding was needed to create the breeds in the first place. “But you can’t keep doing it all the time because you’ll get punished for that,” she says, adding: “You can do DNA tests for a lot of hereditary conditions, but you can’t screen for all potential problems.”

Belgian Shepherd

Genetics can throw up surprises. Kerstin Heinen-Kunath from near Malmedy has bred Tervurens for many years with her husband. They had a bitch called Katja who looked like a Tervuren but whose parents were both short-haired Malinois. “We registered her as a Tervuren with Malinois ancestry and bred her with Tervurens,” she says.

The Belgian shepherds have a lot in common because they were one breed 150 years ago, but there are character differences. Heinen-Kunath says she fell in love with the Tervuren breed partly because they are calmer and easier pets than the dynamic Malinois.

Caroline Thonnon, a breeder of prize-winning Groenendaels from near Hasselt, also distinguishes her preferred breed from the more popular Malinois. “Many people just think Malinois when they talk about Belgian shepherds. It’s a pity, the Groenendael has a much softer expression on its face. They are super intuitive and they are easier family pets than Malinois,” she says.

Until about 30 years ago, Groenendaels were common in Belgium, often seen on farms. But that’s changing. “Groenendaels need space,” Thonnon says. “People are choosing smaller breeds better suited to urban settings; the hybrids like labradoodles are an easier pick. It’s a pity. Groenendaels are part of Belgian heritage – they are its forgotten treasure.”

Raising and training

“The Malinois is the cleverest breed of all, even smarter than border collies,” says the World Federation’s Weckhuyzen. But if you are tempted to get a Belgian shepherd, then he has some valuable tips on how to pick a pup and how to train it.

First, be aware that in every litter, regardless how close the parents are related, you will get puppies with different personalities.

“It is quite easy to see which puppies are dominant and which are submissive. Dominant dogs are much harder to train and manage. Sometimes I advise people against their first choice of puppy when they meet a litter because I know they won’t be able to cope,” Weckhuyzen says.

A Belgian Shepherd on the field after a match between Royal Antwerp FC and Beerschot VA, Sunday 29 September 2024 in Antwerp. Credit: Belga

Picking the right pup is especially important if you are looking for a working dog. Perhaps surprisingly, the army, customs and police will never take a dominant animal. “Aggressiveness is not a good thing because it means a loss of control. You need a controllable dog, one you train to bite, not one that will bite of its own will,” he explains.

Belgian shepherds are big. They weigh between 30kg and 45kg. Worth bearing in mind, especially as the dog gets old and needs assistance getting into a car, for example.

When it comes to training, Weckhuyzen says you have to start early. Puppies should stay with their mothers for two months, but then they should go to their new owner and they should begin training together.

He believes in positive reinforcement, using treats as rewards. He follows a technique used to train dolphins. In the 1960s, dolphin trainers began using operant conditioning, a learning process in which voluntary behaviours are modified by association with the addition of reward.

“We do the same thing, using a clicker and treats with dogs,” Weckhuyzen says. He has a working dog training company called K-9 Detection based in Bredene on the Belgian coast.

Some trainers still use punishment to teach young dogs, including using collars that give the animal an electric shock. “I don’t support these methods, not just because they are cruel but also because they are not as effective,” he says.

Belgium’s love affair with dogs shows no sign of waning, from the Malinois patrolling airports to terriers trotting through my street in Ixelles. The real challenge lies not in training the animals, but in training ourselves – to pick wisely, to treat kindly, and, at the very least, to carry a poo bag. After all, it’s never the dogs that let us down.