The murder of Communist leader Julien Lahaut in 1950 shocked Belgium. No-one was convicted for the murder, and it is still an open wound.

A politicised justice system turned a blind eye to the suspected perpetrators in a clandestine anti-communist network during the Cold War. After the case was closed in 1972, it would take many more years for public inquiries to review the police investigation and explain what went wrong.

The crime scene

Date: 18 August, 1950. Place: The town of Seraing in the Walloon province of Liège. Two men are walking along Rue de la Vecquée. They ask someone in the street where Julien Lahaut lives. Lahaut has moved house the year before, further up in the same street. They want to be sure about where he lives now. A car is parked in front of his former house. The driver steps out, looks at the house and drives on.

The neighbour leads the two men up to Lahaut’s new house. Around 21:15, in the glimmer of streetlights, they approach the modest row house. Lahaut’s wife answers the door. They ask to see Julien Lahaut. She leaves them at the open door to get her husband, who just finished the family meal.

He is left with the visitors and by the time she is back in the kitchen, she hears gunfire. She runs to the entrance and sees her husband fallen with his head against the pavement. The two men run to a car on the other side of the street and shoot twice towards the house.

Julien Lahaut, the 65-year-old chairman of the Parti Communiste de Belgique was murdered. By the time the police arrive, at 21:30, the house is crowded with neighbours and passersby.

Lahaut’s body has already been moved to the kitchen and examined by two doctors. He was hit by four bullets, with the one in his abdomen proved lethal. At 22:00, the Public Prosecutor’s Office is dismayed to see that people had picked up bullets or kicked them around.

His funeral on 22 August was attended by 150,000 people, as reported by the state police (gendarmerie). The simple memorial plate, attached to his house, refers to his murderers as the enemies of the people (les ennemis du people).

The murderers were never formally identified nor brought to justice. After 20 years, in 1970, the statute of limitations was reached. Two years later, after investigations by four subsequent examining magistrates, the case was officially closed. Lahaut left a widow but no children.

A royal incident

One week before the Lahaut murder, on 11 August 1950, 20-year old prince Baudouin swore a constitutional oath before the assembled Parliament and becomes the Royal Prince, receiving the royal title after his father, King Leopold III, who had been forced to abdicate the throne.

Young Prince Baudouin, only 20 years old, during his swearing of the royal constitutional oath, 11 August 1950.

In this way, a compromise was found to the Royal Question in a country on the brink of civil war between monarchists and republicans. But the ceremony was marred by some events in Parliament. In the morning, a little-known incident caused panic. A smoke grenade was thrown towards the benches of the socialist faction by a staunch supporter of Leopold III.

Others were not happy that the old king was to be replaced by his son. The Communist Party wanted a presidential system and a republic to be proclaimed. They had not forgotten Leopold III’s far-right sympathies during World War II, his support for the Nazi “New Order of Europe” and his unwillingness to follow his government in exile.

Julien Lahaut, a popular politician and honorary president of the Communist Party who had survived the Nazi concentration camps, was also part of the second incident, which took place when Baudouin was about to deliver his oath, as planned, at noon. The communist fraction in Parliament yelled “Vive la République! (Long live the Republic).”

What actually happened is not completely clear. According to the memoires of Prime Minister Gaston Eyskens (1905-1988), published in 1993, it was Communist party member Henri Glineur who shouted support for a republic. However, it is now believed to have been his brother Georges Glineur. Eyskens added that after a long applause in support of Royal Prince Baudouin, the cry was repeated by Lahaut. Anyway, it is clear that Lahaut was not the only one who shouted the displeasing words to the royalist supporters during the oath.

It would take almost a year, on 17 July 1951 for Baudouin to be coronated as King of the Belgians, a day after the official abdication of King Leopold III, and after he had reached the legal age according to Belgian law.

When Julien Lahaut was shot dead in front of his house on 18 August 1950, the murder was popularly linked to the incident in parliament a week before. Was he murdered by staunch supporters of the King in revenge for yelling “Vive la République!”? The Communists were seen by the monarchists as a threat to a nation that was trying to heal its wounds after World War II and instate a strong government during the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Perpetrators identified

In 1985, the book De moord op Lahaut was published by historian Rudi Van Doorslaer and Etienne Verhoeyen. Their book was the first scholarly effort to study the Lahaut case and focused on the anticommunist intelligence services, which were active at the time in Belgium and Europe. Their effort started as a response to the documentary television series of legendary journalist Maurice De Wilde, broadcast in 1982, who had made some “unsatisfying accusations” in the Lahaut murder case.

In March 2002, after the success of the Lumumba Commission, Belgian senators Vincent Van Quickenborne (Spirit, later Open VLD) and Josly Dubié (Ecolo) wanted the murder of Lahaut to be researched as well. In May 2002, Van Quickenborne saw La dissection d'un homme armé, a play by Stijn Devillé, in which the Lahaut murder case is fictitiously solved.

This inspired Van Quickenborne to conduct his own preliminary research. He consulted the Lahaut file at the State Archive of Liège, where the name François Goossens quickly drew his attention. Interestingly, the original dossier was mistakenly destroyed in the mid 1990s, but a copy of the 11,000-page dossier had survived and been placed in the State Archive.

Julien Lahaut’s grave and monument at the cemetery of Seraing, which states “loved son of the working class of Belgium and the international proletariat”, “tireless fighter for peace and liberty” and also refers to his murderers as “enemies of the people”. Every August 18, he is still commemorated by large groups of supporters, carrying red flags of the Communist Party of Belgium (PCB).

According to Van Quickenborne, hundreds of leads were examined in the case, some far-fetched, but “important traces, leading to François Goossens were left unresearched by the examining magistrate.” This made him wonder whether the “investigation was sabotaged or whether the magistrate was incompetent.” He wanted a parliamentary research commission to find out who ordered the murder and did not doubt that they were “anti-communist royalists.”

Already in the 1985 book, De moord op Lahaut, the two authors had discovered the name of François Goossens who had died in 1977. However, in agreement with the family, they choose not to make his name public.

In January 2003, the newspaper De Morgen reported that former Belgian spy André Moyen (1915-2008) had confirmed that Goossens was connected to the Lahaut case and was joined by a son of the mayor of Halle, Jan Niklaas Devillé (1888-1965).

Julien Lahaut before WW2, representative for the Communist Party of Belgium (PCB) in the city council of Seraing and for the Province of Liège since 1929.

On 4 December 2007, news media in Flanders reported that an anonymous man from Halle had confessed to his role in the shooting of Julien Lahaut. This was to be featured in a documentary series fittingly called Keerpunt (Turning Point). This witness was granted anonymity through a written agreement. According to the documentary makers, he was only prepared to come forward after being convinced that the case was indeed closed.

The man was granted anonymity but since he talked about François Goossens and his own “brother and brother-in-law” being involved, he could later be identified as Eugene Devillé. In an ironic twist, he was one of the uncles of theatre director and playwrighter Stijn Devillé, who was inspired to write his play by the “mystery stories” in his family about the Lahaut murder case. His brother-in-law was identified as Jan Hamelrijck.

Missing funding

In May 2008, a proposition to review the case was prepared by historian and senator Pol Van Den Driessche (then CD&V), supported by other political fractions. The research was to be conducted by CEGESOMA (Centre for Historical Research and Documentation on War and Contemporary Society).

This research centre was founded in 1967 as Centre for Research and Studies on the History of the Second World War. In 1997, it broadened its mission to the whole 20th century and changed its name. Today it is a division of the State Archives and is housed in the centre of Brussels at the Luchtvaartsquare – Square de l’Aviation 29.

The senator’s proposal was signed in November 2008 by all the majority fractions in Parliament, after which the necessary budget was presented. By December 2008, the Belgian senate’s Justice Commission accepted the proposal, but a year later the necessary funds had not yet been approved.

When the proposed budget of €800,000 was reduced by half, the reluctance of the Belgian federal government for funding was offset by a decision of the Walloon government. Walloon Minister of Research Jean-Marc Nollet made €150,000 available, which along with €40,000 from public collections enabled the researchers at CEGESOMA to start their work in May 2011. There was now enough funding for a first year of research. More funding was allocated in August 2012 by federal Minister for Science Policy, Paul Magnette, which permitted a second year of research to take place.

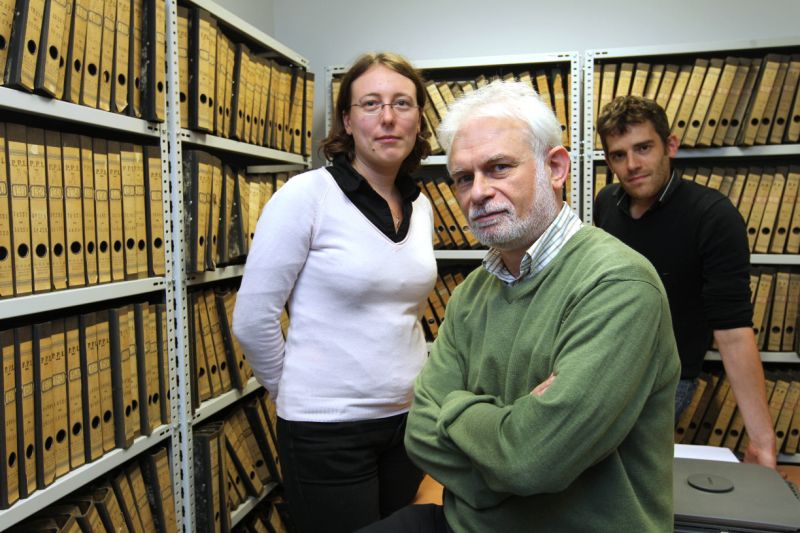

Two postdoctoral senior researchers, Widukind De Ridder (VUB, Brussels) and Françoise Muller (UCL, Louvain-la-Neuve) carried out the study, led by historian Professor Emmanuel Gerard (KU Leuven), who had been a member of the panel of experts in the parliamentary commission of enquiry into the Lumumba case.

The results of the research were officially presented to the Belgian Senate in May 2015. The various media reported how “meticulous historical research painfully exposed the combined efforts between public and private security services effectively having sabotaged the investigation into the murder of Communist leader Julien Lahaut.”

Cold war network

The well-written book by historians Emmanuel Gerard, Widukind De Ridder and Françoise Muller firmly points to the so-called Network led by André Moyen. Its actions fit in the Cold War strategy of tension, aimed at stoking fear and reactions from organizations and persons attacked so that strong measures could be taken. Interestingly, only a few months after the Lahaut murder, communists were dismissed from the government and banned from employment in public administration. The employment ban would continue until the 1960s.

André Moyen, known for his anti-communist “Network”. US Senator Joseph McCarty actions against communists in February 1950 also heightened the fear for “the fifth column” in Belgium.

In fact, the fear of communism was exaggerated. Gerard writes in a paper from 2016 that communist strength in Belgium had been sharply declining since the end of the war. The Communist Party, which was part of the Belgian coalition government between 1944 and 1947, became more and more isolated at the end of the 1940s. The broad sympathy which the communists enjoyed after the liberation had vanished by 1950.

Moyen’s Network was financed by Belgian private companies: Société Générale (later Fortis Bank), its subsidiary Union Minière du Haut-Katanga and Brufina (large shareholder of Bank of Brussels, now ING). Their research showed that the case, with all its relevant documents, had been mishandled by the police, politicians and the secret service agencies of the state.

André Moyen reported to Minister of Interior Albert De Vleeschauwer, police and secret services. According to the authors, it proves the involvement of official and private intelligence services in planning the murder and obstructing justice in the investigation. In every inquest by the justice department during the investigation in 1950-1972, any role André Moyen could have played was immediately minimized.

Stay-behind networks

André Moyen used his work as journalist as a cover for his activities in the network. In June 1951, not under oath, Moyen told magistrate Louppe that he “knows absolutely nothing about the case” and denied having told anyone about the murderers or the circumstances. Interestingly, the last part is technically true.

A written report by Moyen was found by the researchers in the papers of Minister De Vleeschauwer, archived at the KADOC in Leuven, titled Activité du Reseau pendant le mois de août 1950. De Vleeschauwer was Minister of the Colonies from 1938 until 1945. Since 1948, Moyen was one of the forces behind the Crocodile Network in Congo, fighting “Soviet and subversive elements.”

In the report, Moyen calls Lahaut “an agent of the Soviet Union.” He states that he was murdered as a warning to the government for “not taking action against the fifth column.” If “people of the government are murdered,” as retaliation for the Lahaut murder, then “it’s their own fault,” for not having taken action earlier.

Interestingly, he wrote that the murder was enacted “by an apolitical group,” which initially only wanted to “come into the picture when occupied by the Soviets.” He called it a synarchy, a term to denote its strong influence in many circles, including the police investigators. The report was also found in the archives of Antwerp Judicial Police and at Union Minière. Interestingly, the last part of the report concerning the motive is missing in the copies.

In August 1990, Italian Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti confirmed the existence of the “stay-behind” network Gladio, later supervised by NATO. He was followed by Belgian Minister of Defense Guy Coëme who confirmed their Belgian branch, leading to a parliamentary enquiry in 1990-1991.

The Standing Committee was founded as Belgium’s intelligence agencies review committee and is supervised by the Belgian Parliament to oversee any covert operations. According to Professor Emmanuel Gerard in a 2016 paper, "the Moyen Network had the appearance of a stay behind group, but there is no evidence for its integration into the official stay behind networks."

Could a better grip on the actions of these networks solve other mystery murder cases in Belgium? Or could they finally be solved by historians?

| “The Belgian judiciary can fail again” In 2011 – 2015, historian Emmanuel Gerard at KU Leuven University led a research project into the murder of Julien Lahaut. The research, commissioned by the Belgian senate, was followed a year later by a paper where he elaborated on the anti-communist campaign in Belgium during the cold war. Emmanuel Gerard spoke to The Brussels Times about his thoughts on the matter.  Historians E. Gerard (center), F. Muller and W. De Ridder pictured in 2012. The team have extensively studied the archives and case of the Julien Lahaut murder. Credit: Yves Logghe Q: The first scholarly study in 1985 discussed four possible hypotheses to explain the murder: 1) an act of revenge by royalists, 2) internal settling of scores within the Communist party, 3) the cold war and 4) an anti-communist “strategy of tension”. In which do you believe most? A: We dismissed the first hypothesis. The murder wasn’t connected to the Royal Question as such. The second hypothesis is even less plausible since there was no indication of persons or motives involved. As to the third hypothesis, it’s clear that the murder was part of Cold War strategies, but there are no indications (until now) that the Moyen network answered to the CIA. The fourth hypothesis is plausible, but not with the aim of bringing Leopold back on the throne, rather to see the government take measures against the communists after their expected violent reaction. Q: Why did the Belgian justice system fail? Was it mainly because of collusion with the Moyen network or were the police unprofessional and ineffective in carrying out the investigation? A: The Liège justice authorities did make serious efforts to solve the case, but the judicial police, connected to the Moyen network, thwarted the actions of those responsible for the investigation. Q: Could the justice system fail again today? A: Yes, look at the unsolved case of the “Brabant killers” - 28 people killed in several (maybe terrorist) attacks on supermarkets in the 1980s; the statute of limitations has been brought to 40 year to make it possible for the justice system to bring the culprits to justice. Q: Your study was thorough and had access to all archives. Does it mean that any later studies will mostly be concerned with the interpretation of the facts or are facts still missing? A: The main facts are known and, unless unexpected documents would be unearthed, historians will continue to discuss various interpretations. There is also room for more research on the role of private companies and of the US. Q: Would you say that Belgian society has come to terms with the murder or is it still an open wound? A: For most people, all this happened a long time ago. Public debate has subsided. The case has been solved and closed since our investigation, although some questions remain unanswered. |

By Tom Vanderstappen