When Belgium unveiled the Congo Panorama at the 1913 Ghent World Exhibition, it was meant to astonish.

Stretching an almost unbelievable 115 metres in length and 14 metres in height – more than 1,600 square metres of painted surface – the colossal canvas wrapped inside the walls of a purpose-built rotunda, transforming visitors into spectators inside an imagined Congo.

It was a monumental act of image-making: an engineered illusion designed to convince 1913 spectators of the supposed success and benevolence of Belgium’s “civilising mission.”

The Belgian state, freshly in control of the Congo after the scandals of King Leopold II’s brutal private regime, needed to present a sanitised, triumphant new narrative. The panorama was designed to do exactly that: a nation-sized piece of propaganda, vast enough to blot out atrocity.

More than a century later, the original canvas remains rolled up in storage in Ypres, far too fragile and logistically unwieldy to exhibit.

But this Friday, AfricaMuseum in Tervuren opens The Congo Panorama 1913. Colonial Illusion Exposed, an exhibition that resurrects and dissects the giant painting through a new large-scale reproduction, together with archival material. The result is not a spectacle, but a takedown.

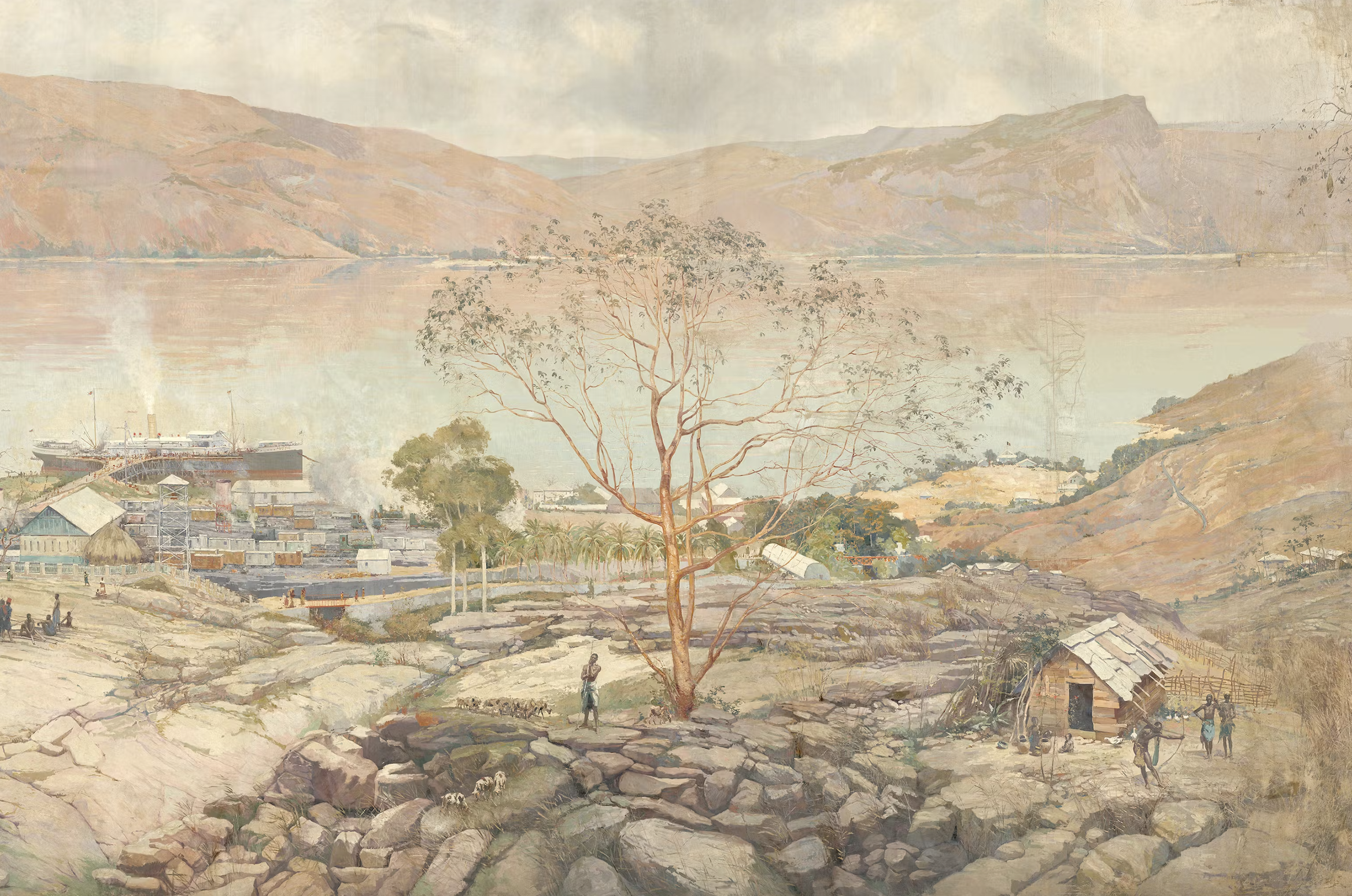

A section of the Congo Panorama by Alfred Bastien

The panorama was commissioned in 1911 by Minister of Colonies Jules Renkin, who tasked painters Alfred Bastien and Paul Mathieu with producing nothing less than a total visual justification of Belgian rule. The artists travelled for five weeks between Matadi and Léopoldville (now Kinshasa), returning with photos and sketches later expanded into the colossal canvas, supported by a small army of landscape, market and sky painters.

In the Panorama, they merge into a single, harmonious landscape designed to suggest Belgian mastery over a vast, unified territory.

The 1913 rotunda was built in Ghent’s Citadelpark - where the Museum of Fine Arts, MSK, and the contemporary art museum, SMAK are now, along with the Kuipke velodrome. It was designed for maximum impact. Visitors entered through a dark tunnel before emerging onto a central viewing platform, surrounded on all sides by a continuous horizon of verdant forests, bustling markets, majestic waterfalls and modern Belgian infrastructure.

The canvas shows calm fishing scenes, villagers dancing, goods being unloaded efficiently from steamers. Belgian engineers and missionaries appear as benevolent modernisers delivering progress: steamships, railways, iron bridges.

A “faux-terrain” of sand, rocks and cut-out figures at the base of the canvas enhanced the immersion, while a canopy hid the ceiling and edges. The effect was a kind of early virtual-reality trick – a total environment.

Alfred Bastien painting the Congo Panorama

“It looks amazing, but the message is horrific,” says historian Maarten Couttenier, the curator of the exhibition. “The panorama was constructed so that spectators left with a pleasant idea about Belgium in Congo,” he tells The Brussels Times.

Its omissions are glaring. Nowhere is the forced labour that underpinned every tonne of transported rubber, ivory and minerals. Nowhere are the countless porters compelled to haul goods inland. Nowhere is the human cost of the Matadi–Kinshasa railway, which claimed unrecorded numbers of Congolese lives.

The government’s aim was to distract from the atrocities of the Congo Free State and recast Belgium as a modern, humane colonial power.

The panorama thus served as the centrepiece of a broader propaganda machine: dioramas in the same pavilion glorified missionary activity, shipping lines, agricultural schemes and industrial expansion. The charming pastoral scenes on the canvas occlude a system defined by extraction, domination and racial hierarchy. Couttenier notes how prisoners had to be repainted without their chains – one small example of the sanitising edits demanded by colonial officials.

The Panorama of Congo

The original canvas exists today only as a 15-metre-long roll weighing several tonnes (it was badly damaged during the Second World War by the Nazis, who thought it was a cannon and sawed through it).

The War Heritage Institute, which stores it, needed two army tank cranes merely to unroll it for photography in 2022 – the first time it had been opened in nearly 90 years. Photographers created more than 830 ultra-detailed 100-megapixel images, later stitched into a digital reconstruction exceeding seven gigapixels.

Physically displaying the canvas is unlikely ever to happen. “If you want to exhibit the original, you’d need a special building – it would cost €20 million,” Couttenier says. “It might never be displayed again.”

AfricaMuseum’s exhibition does not attempt to recreate the old spectacle. Instead, it lays out the panorama’s mechanisms of deception and juxtaposes them with Congolese voices, both archival and contemporary. A sound installation confronts visitors with recordings from 1912 – including Kaliko songs of flight and death that pierce the idyllic imagery.

Africa Museum in Tervuren. Credit: Erard Swannet

The exhibition also places preparatory sketches, photographs and archival records alongside responses from contemporary artists such as Shurouq Mussran, interpreting what the painting concealed.

AfricaMuseum is itself a controversial building. It was the site of the notorious 1897 International Exposition, which Leopold II used to showcase his plunder from Congo – including his ‘human zoo’ of Congolese tribespeople put on display.

Later remade as the Congo Museum and now formally known as the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA), it underwent a major overhaul a decade ago, acknowledging its role in upholding Belgium’s colonial rule. “The museum used to be a colonial propaganda machine,” Couttenier says. “Now we’re trying to do the complete opposite.”

By centring a reproduction of the Congo Panorama – not to admire it, but to expose it – AfricaMuseum is trying to turn the gargantuan painting into one of its most important documents of deception. In doing so, the exhibition invites visitors to look harder at grand narratives, grand illusions and the political uses of beauty.