In the long and secretive history of the British secret service, MI6, two intelligence networks stand out for special acclaim – and both operated behind German lines in occupied Belgium.

The first, La Dame Blanche (The White Lady), emerged during the First World War; the second, the Clarence Service, followed in the Second World War. MI6’s official history hails La Dame Blanche as "the most successful single British human intelligence operation of the First World War".

Of its successor network, the Clarence Service, it states that, “by the quality and quantity of the messages and documents which it provided, Clarence was the highest among the networks of military information of all occupied Europe.” Such distinctions are rare and revealing.

La Dame Blanche was named after an ancient German legend that if a ghost of a white lady appears to the German army on the battlefield, it would herald the downfall of the Hohenzollern royal dynasty, Brandenburg-Prussia’s ruling family, and thus the mighty Imperial Germany.

It was no coincidence, then, that it was given to one of the most important intelligence networks behind the German lines in the First World War. The imagery was clear – that by its clandestine intelligence gathering work for the British secret service, La Dame Blanche would bring an end to German occupation in Belgium. And it did.

A secret camera and a fake Nazi stamp

Many patriotic Belgian women and men took part in clandestine missions and intelligence-gathering in both world wars. They were strong leaders, agents, couriers and spies – and all at the very heart of these two MI6 networks.

They collected information on troop movements and defences behind the German lines, wrote coded reports and messages which were smuggled out of Belgium to British intelligence in Rotterdam, set up safehouses, ran letterboxes and established courier lines.

The agents delivered critical eyewitness information that helped British intelligence and Allied commanders in the field build a picture of German positions behind the lines, the geographical regions where the troops were located and the enemy’s fighting capability.

Information on troop movement in a particular direction enabled a prediction of the area for the next German offensive against Allied positions along the front line.

Risky work

The first leader of the network was Dieudonné Lambrecht, an engineer from Liège. He led an army in the shadows – without uniform or guns, but whose members took an oath of allegiance and were given military ranks. The women, like the men, swore allegiance and were given a rank – and in some cases, they outranked the men.

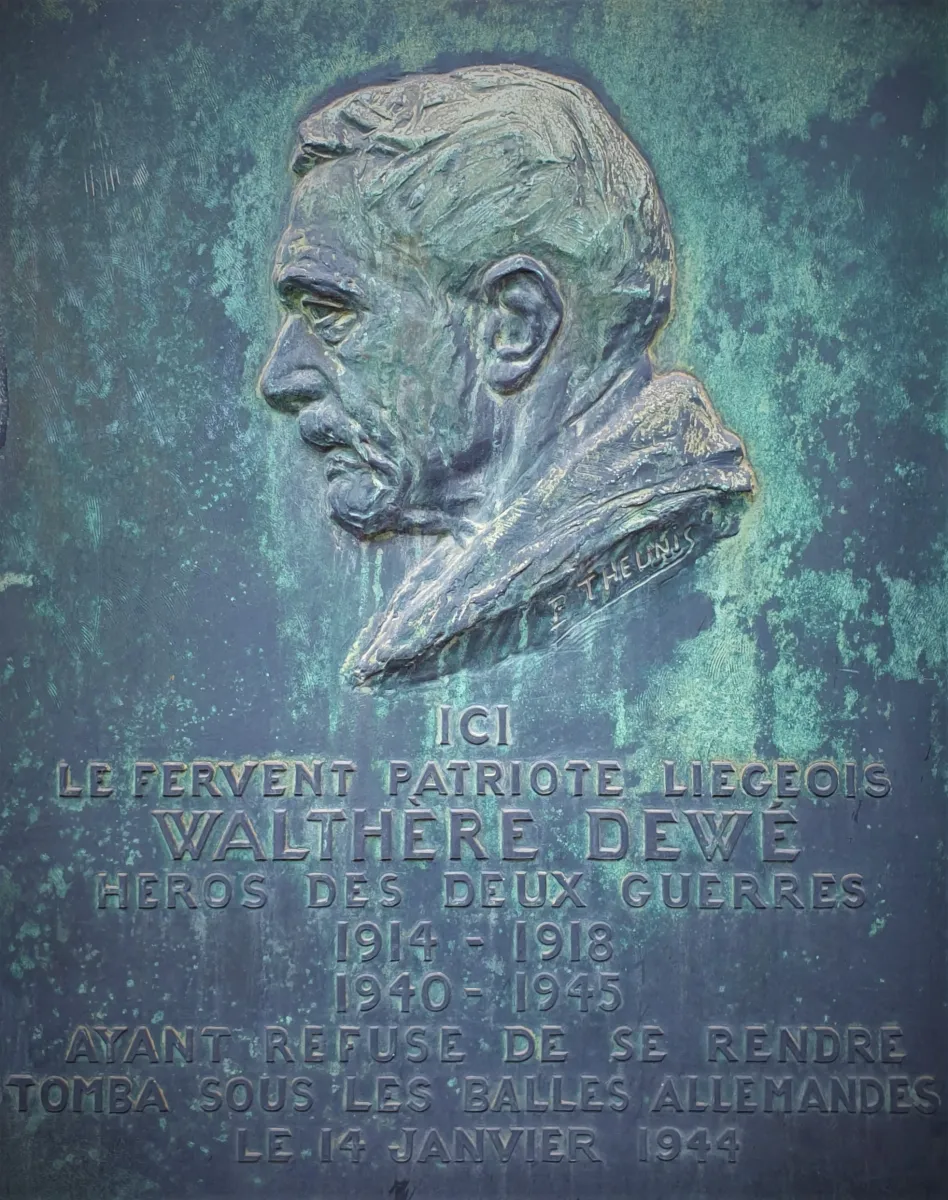

They always faced the risk of being discovered by efficient German counter-espionage units, and this was indeed the case with Lambrecht, who was arrested and shot at Liège’s Fortress of the Chartreuse on April 18, 1916. However, in death, Lambrecht became a powerful figure who inspired others to continue with his work. His cousin Walthère Dewé took over the leadership and the network was renamed La Dame Blanche.

Over 40 agents initially worked for La Dame Blanche, but by the end of the war, the network had expanded across Belgium and had 1,084 agents. Theirs was a great sacrifice: if captured, they suffered brutality and torture during interrogation, and could be shot. They knew this but continued their work nonetheless. They understood the importance of their operations for the Allies.

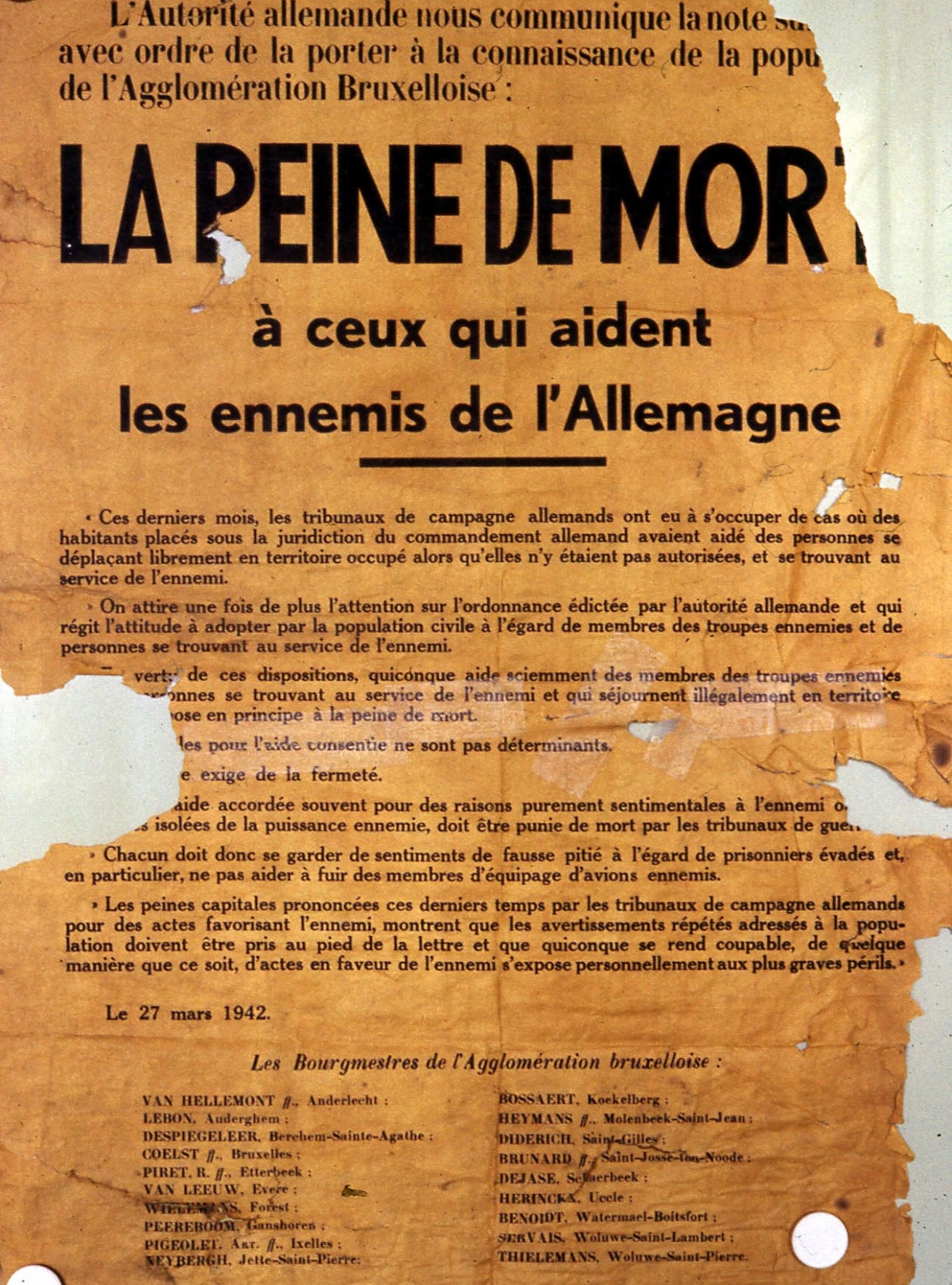

Poster threatening assassinating resistance fighters

Women were prominent in the network’s success. They moved invisibly behind the German lines, with the Germans not expecting women to be involved, but rather seeing them as housewives and keeping the family.

At the heart of this history are strong personalities, like Lambrecht, Dewé, Thérèse de Radiguès and the Tandel sisters. The doughty de Radiguès operated from her home at Conneux Castle and ran an entire intelligence section from the region around Ciney, sending agents into the German-occupied Luxembourg.

In the early years of the British secret service, which had only been founded in 1909, heroic Belgians were developing all kinds of early spy techniques, using invisible ink in messages, knitting coded messages into jumpers and scarves, hiding messages in clumps of mud or potatoes, and smuggling reports over the border into the Netherlands for the British.

Recalling the old guard

When the call came again in 1939, many of the same men and women, albeit much older, did it all again for the successor network called the Clarence Service.

On September 3, 1939, Britain declared war on Nazi Germany after Germany had invaded Poland two days earlier. Dewé, then 59, was contacted by a British secret service agent codenamed ‘Daniel’ (Claude Cyril Barnes-Stott) who said that MI6 had an important mission for him.

Dewé was asked to call up the old guard and set up an intelligence network in Belgium again. It was modelled on La Dame Blanche, but modernised and with spycraft modified for a new era.

Belgian Resistance fighter Thérèse de Radiguès

MI6 was under no illusion that Germany might seize Belgium again. Dewé set up observation posts as an early warning system to collect information to alert MI6 if a German invasion was imminent.

In May 1940, Germany occupied Belgium again, and Dewé’s network expanded to take in a new generation of agents. The network was named the Clarence Service after his co-leader, Hector Demarque (codename ‘Clarence’). As before, its agents and couriers were militarised and given military ranks.

Women operated as heads of intelligence sectors, couriers, agents and ran letterboxes and safehouses. They were as courageous as the men and undertook the same personal risks.

Thérèse de Radiguès and the Tandel sisters were once central to the leadership and operated as agent handlers: their sectors went on to deliver crucial V-weapon rockets (V-1 and V-2) intelligence for MI6 from behind enemy lines, including the positions of V-1 installations. Dewé, alas, would be shot in Ixelles as he fled from the Nazis after leaving de Radiguès’s house at Avenue de la Couronne 41 (a plaque at the spot where he was killed is on the wall of Rue de la Brasserie 2).

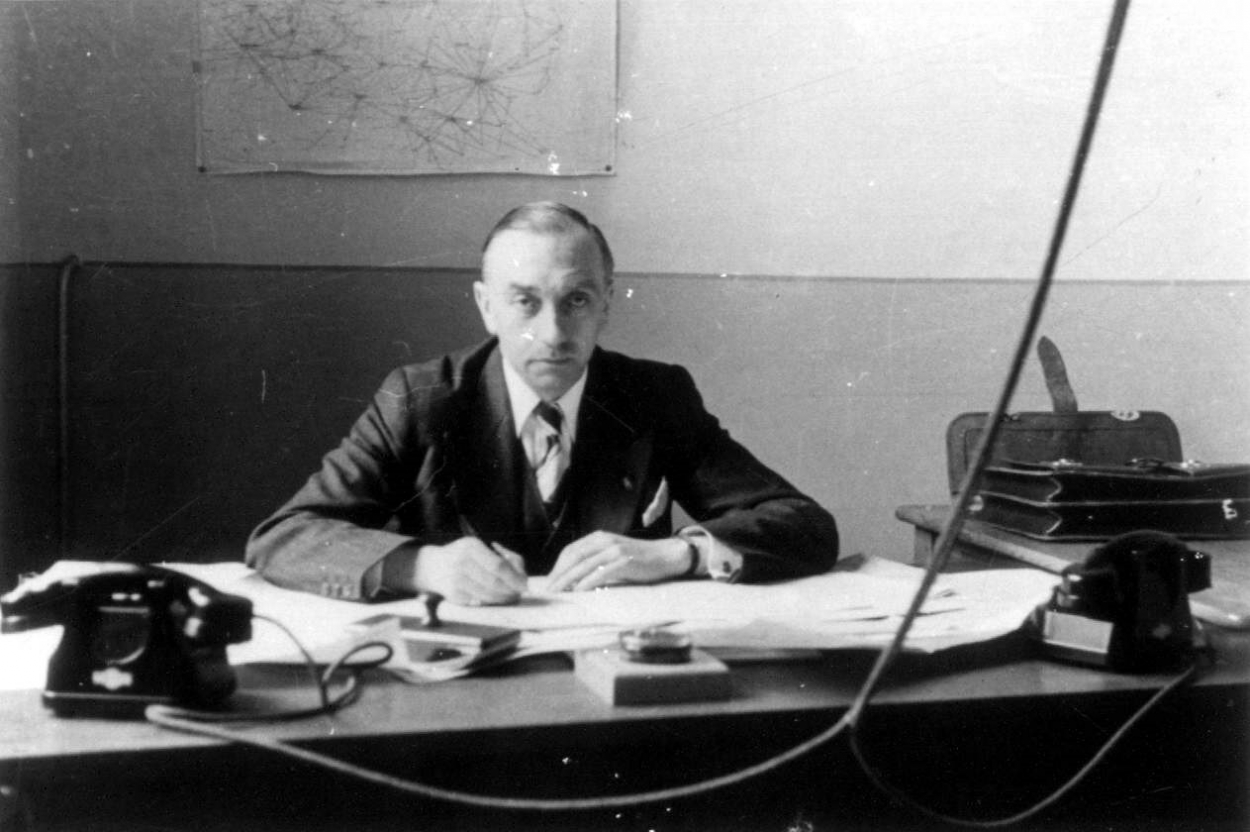

Belgian agent from WW2, Hector Demarque

From the London end, operations were headed by ‘Major Page’, the codename for Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Jempson, who headed the Belgian section of MI6. Working with him was MI6 officer Ruth Clement Stowell.

She was an agent handler who organised the training and planned the secret missions of the agents being parachuted into both Belgium and Luxembourg. She oversaw the missions, often being the last person to see the agents as they left on their flight from England for Belgium.

The Clarence Service not only operated in Belgium, but dispatched agents over the border into northern France, where they were particularly active along the coastline and near sites of German defences. Other agents were sent deep undercover into Nazi Germany to gather information on German military capability, new weaponry and technology, as well as positions of German fighting units.

Their observation posts sent an extraordinary volume of detailed military intelligence across the war that was included in 160 reports. Intelligence reports in the nine months before the D-Day landings in Normandy, on June 6, 1944, provided volumes of valuable information on German troops and their movements, reports of the results of Allied bombing raids on engine sheds and locomotives, enemy activity at aerodromes, and sketches of a range of important sites, including the Belgian and French railways and docks.

Blueprints of stations and rail lines were smuggled out to London. These are the impressive blue and white technical plans which unfurl to a length of two to three meters and survive today in the archive of the Clarence Service at the Imperial War Museum in London.

Just a fortnight before D-Day, reports were urgently sought by MI6 on the markings on enemy aircraft, types of aircraft engines in production, as well as the manufacture of special equipment and weapons, the movement of planes, the location of headquarters, and the state of the railways and traffic in Belgium and Northern France.

Clarence Service agents sent MI6 updated material on this. The vast intelligence-gathering across Belgium, into northern France and Luxembourg by Belgian agents was simple but effective.

Courage under fire

What emerges from this is a story of defiance, heroism and ingenuity that saw Belgian women and men engaged in daring acts of espionage behind the German lines. These networks sprang from the initiative and courage of ordinary Belgians.

La Dame Blanche and Clarence Service networks are important in the history of MI6, too. More British historians and researchers should study the now-declassified files of other clandestine Belgian networks- so far, they have barely been consulted outside Belgium.

I hope the courage and selfless sacrifice of the Belgian agents and parachutists will become known more widely outside Belgium. They played an enormous part in the defeat of the occupying German forces and in the restoration of democracy to Europe.

I have only tapped the surface of Belgium’s espionage history, but there is already a sense emerging of the strategic intelligence importance of Belgium in two world wars. Belgium’s secret networks may emerge, in fact, as the greatest intelligence asset to the Allies during two world wars and outweigh other countries that have been the focus of war studies for the last 30 to 40 years.

These stories are important to tell because they let us learn the lessons of history and, most importantly, to understand the price paid for the freedoms that we enjoy today. It was Peggy van Lier, a Belgian agent of the Comet escape Line of World War Two, who once said, “It is only when you have lost freedom you realise it is the most precious thing.”

The courageous Belgian women and men who worked in La Dame Blanche and Clarence Service, and the many other resistance and intelligence networks in Belgium, understood this. We owe them so much.