Bob De Moor is one of the few artists whose work is known to millions, even if his name is not.

For 35 years, he was Hergé’s closest collaborator – the man who helped give Tintin’s adventures their physical reality, from rockets and laboratories to deserts, ships and, most famously, the surface of the Moon itself.

A century after his birth in Antwerp on December 20, 1925, De Moor remains one of the great paradoxes of European comic strips: inseparable from Tintin, yet still too often confined to the margins of its story.

From the early 1950s onwards, as Tintin became increasingly ambitious and technically complex, De Moor emerged as Hergé’s indispensable craftsman.

While Hergé remained the undisputed author – drawing the characters, shaping the narrative and retaining final control – De Moor was responsible for much of the world those characters moved through. De Moor, who died in 1992, aged 66, designed settings, supervised other artists, and ensured continuity across albums that were built with almost obsessive care.

Nowhere is that contribution clearer than in Destination Moon and Explorers On The Moon. The red-and-white chequered rocket rising between mountains and scaffolding, the laboratories at Sprodj, the gantries and launch infrastructure, the rocket’s interiors and, ultimately, the lunar surface itself: these are images that define Tintin’s space adventure.

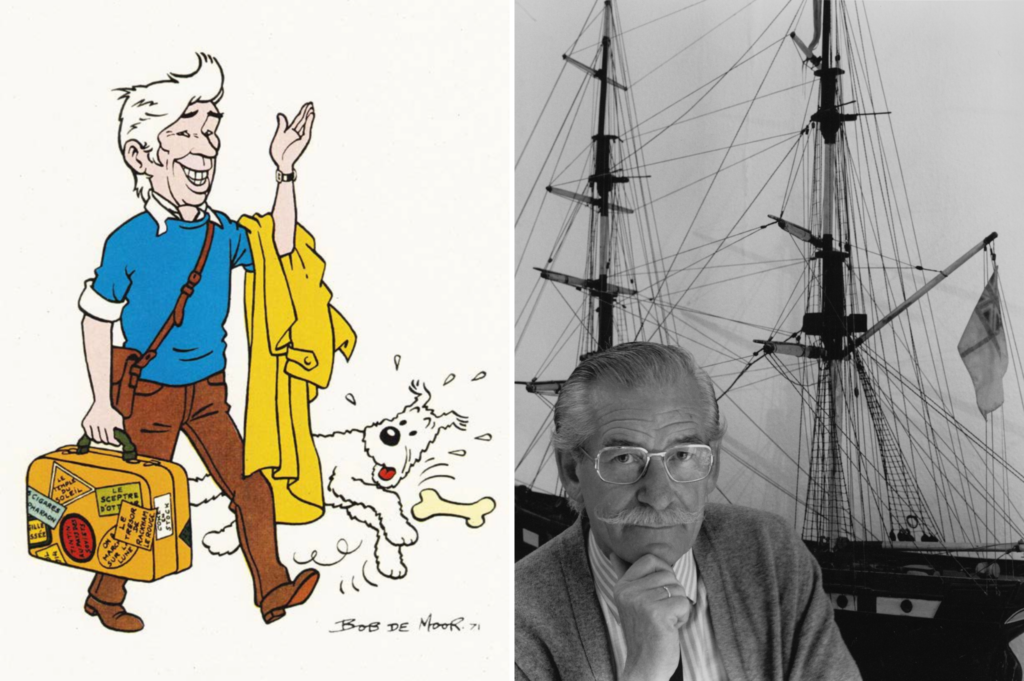

Tintin by Hergé and illustrated by Bob de Moor.

According to Gilles Ratier, De Moor’s biographer, the Moon as readers know it was “obviously conceived” by De Moor – from its relief and shadows to its imagined geological features. Even decades later, De Moor would joke that when Apollo footage finally arrived in 1969, his mountains were “not quite right.”

Ratier, whose book, Bob De Moor La ligne claire d’Hergé, has just been published, says the illustrator genuinely was Hergé’s right-hand man, especially in the later years. “De Moor designed most of the settings in the Tintin adventures, especially from the later albums onward,” Ratier says. “As head of the Studios Hergé, he also supervised other artists and handled advertising illustrations and related work.”

One full-page image of the rocket on its launchpad alone took him three weeks of work. Its perspective and scale were emblematic of a career spent shaping some of the most iconic images of 20th-century comics while rarely stepping into the spotlight.

Ratier recounts the story of how De Moor was brought into Hergé’s orbit after being asked to redraw a Tintin illustration for a Flemish publication. “Hergé was presented with the two drawings and reportedly couldn’t tell which one was his own,” he says. “De Moor was hired almost immediately.”

After Hergé's passing, De Moor supervised the Tintin mural that covers the walls of the Stockel Metro station. And after the death of Edgar P. Jacobs, another former Hergé collaborator, he completed Jacob’s final Blake & Mortimer adventure.

Hergé and Bob de Moor

Yet De Moor was never simply Hergé’s lieutenant. He was an artist of remarkable independence and range. While life at the studio gave him security and freedom from administrative burdens, it also allowed him to pursue his own work - often late into the night. Series such as Barelli, Monsieur Tric and Balthazar revealed a playful, humorous sensibility distinct from Tintin’s controlled realism.

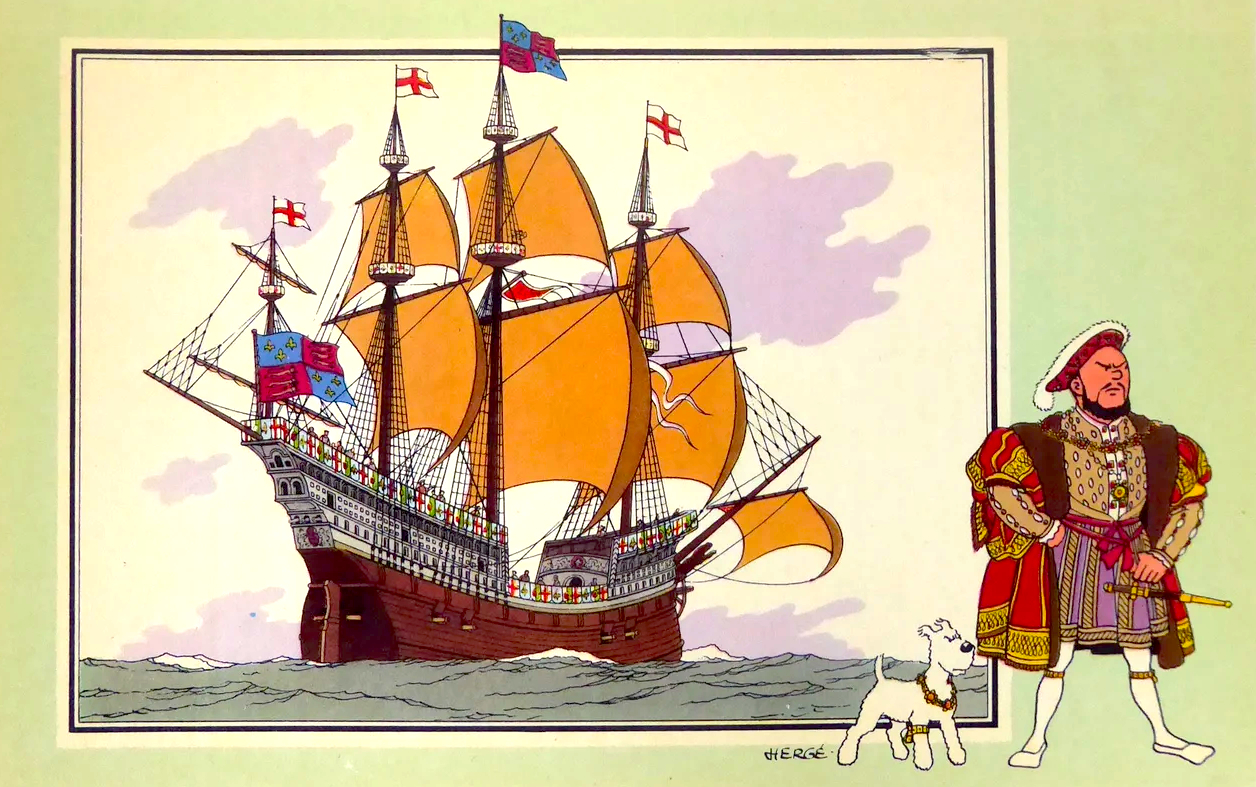

His most accomplished personal work, however, was Cori le Moussaillon, a historical adventure series rooted in his fascination with maritime history. Combining meticulous research with elegant storytelling, it showed De Moor at his most confident and expressive. In 1988, it earned him a major prize at the Angoulême Festival – belated recognition for an artist whose reputation had long been overshadowed by the success of the world he helped build.

Language and geography played their part in that imbalance. Much of De Moor’s work was published first in Flemish newspapers and magazines, with limited translation into French. Where translations did appear, they often failed to find a wide audience. The result was a curious split: an artist revered by peers and specialists, but under-recognised by the broader public.

Ratier’s biography draws on family archives and decades of interviews, reconstructing not just De Moor’s career, but the collaborative reality of Studios Hergé. It also dismantles the idea of De Moor as a frustrated or constrained artist. He never sought co-signature on Tintin, never claimed authorship where he felt it did not belong. “What mattered was the finished work,” he once said. Hergé, for his part, praised his collaborator’s “professional conscience” and extraordinary capacity for work.

Henry VIII comic by Hergé and illustrated by Bob de Moor

Those who knew him describe a man of warmth and humour, whose generosity shaped the atmosphere of the studio as much as its output. His son Johan has placed him, half-jokingly but tellingly, among the great Flemish masters – not the loudest voice, but one whose craft endures through precision rather than spectacle.

The centenary itself has been marked modestly: talks, small exhibitions, a handful of events. There has been no grand institutional revival. Today, De Moor’s work survives largely thanks to small, committed publishers rather than major houses.

Yet his legacy is everywhere. Every time Tintin steps onto the Moon, walks through a laboratory, or stands dwarfed by a rocket ready for launch, Bob De Moor is there – just out of frame, shaping the world, content to let the work speak for itself.