This year, 2026, was only a few days old, and the world was already confronting a new form of instability.

The detention of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro by the United States introduced a fresh point of tension in an international environment where adherence to justice, rules, and restraint is already under pressure.

According to the Global Peace Index 2025, there are 59 active conflicts between states worldwide, more than at any point since the Second World War. Yet this vicious trend can be reversed. Conflict is not inevitable.

With sustained diplomatic commitment, public engagement, and thoughtful decision-making, societies can still move toward a more stable path. Even where the situation appears hopeless today, peacebuilding can make a difference in ensuring tomorrow is different.

Hard v soft power: investing in defence is not enough for security

Last year, 2025, saw unprecedented cuts to development cooperation. The United States, Belgium, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and beyond, governments made decisions that directly or indirectly resulted in reduced budgets for development cooperation.

Cuts to foreign aid may seem like a distant, abstract policy choice. For many communities around the world, however, they can mean the difference between life and death. The consequences of austerity measures often only become visible weeks or months later, as seen in Nigeria.

There, multiple forms of violence reinforce one another: ethnic tensions, local power struggles over land and water, economic insecurity, and religious tensions overlap, creating a complex reality. When international support disappears, it is not only projects that come to an end, but also the fragile structures that help prevent violence, often with devastating consequences.

Civilians in eastern DR Congo. Credit: Belga

These decisions in 2025 built on a trend that has been unfolding for several years: a growing number of violent conflicts worldwide. At the same time, the peacebuilding field is facing a critical shortage of adequate, high-quality funding, significantly weakening the implementation of effective peacebuilding initiatives and policies. Traditional European donors, including the EU, are reducing allocations to development cooperation, with peacebuilding funding now at a 15-year low globally.

While investment in defence is important, it cannot, on its own, guarantee security. Yet, the dominant policy response continues to prioritise increased defence spending, with limited attention to conflict prevention and peacebuilding. This is not an either-or choice, it is a both-and imperative. The world is undergoing profound change, and our security requires an integrated approach. Peacebuilding is essential to addressing the root causes of war and conflict.

Peace has never been more relevant, yet it is increasingly understood in a narrow terms

War, security, and peace have never been so prominent in public debate, yet peace itself is often narrowly defined. The word is ubiquitous in the media. As the director of a peacebuilding organisation, that should be reassuring. In reality, however, the definition of peace used in the media and by policymakers is frequently and superficially limited.

Demonstrations outside the U.S. embassy in Brussels underscore the widening gap between European public opinion and Washington’s increasingly unilateral use of power. Credit: Belga

Attention tends to focus on a handful of high-visibility conflicts, a temporary ceasefire, or the announcement of yet another “peace deal”, as if peace were a snapshot in time. But real peace is far more ambitious. It is about rebuilding trust in societies that have been torn apart by violence, ensuring justice, and engaging in difficult conversations, often with those we most strongly disagree with.

Peace is not a transaction around resources, a temporary ceasefire, or a decision taken by leaders without meaningful involvement of affected communities. True peace requires addressing the root causes of conflict, so violence cannot return.

A different kind of leadership

Achieving this will require a different kind of leadership - at the individual level, across companies and organisations, and on the global stage. Leaders who know how to respond to polarisation, not by ignoring or amplifying divisions, but by actively bridging them.

This work begins with trust: building credibility through the transparent use of power and responsibility, and always starting with the creation of a safe environment. Only when people feel safe do they dare to speak openly about difficult and divisive issues.

It is this kind of leadership that brings people together across divides by acknowledging multiple perspectives and paying attention to underlying emotions and dynamics.

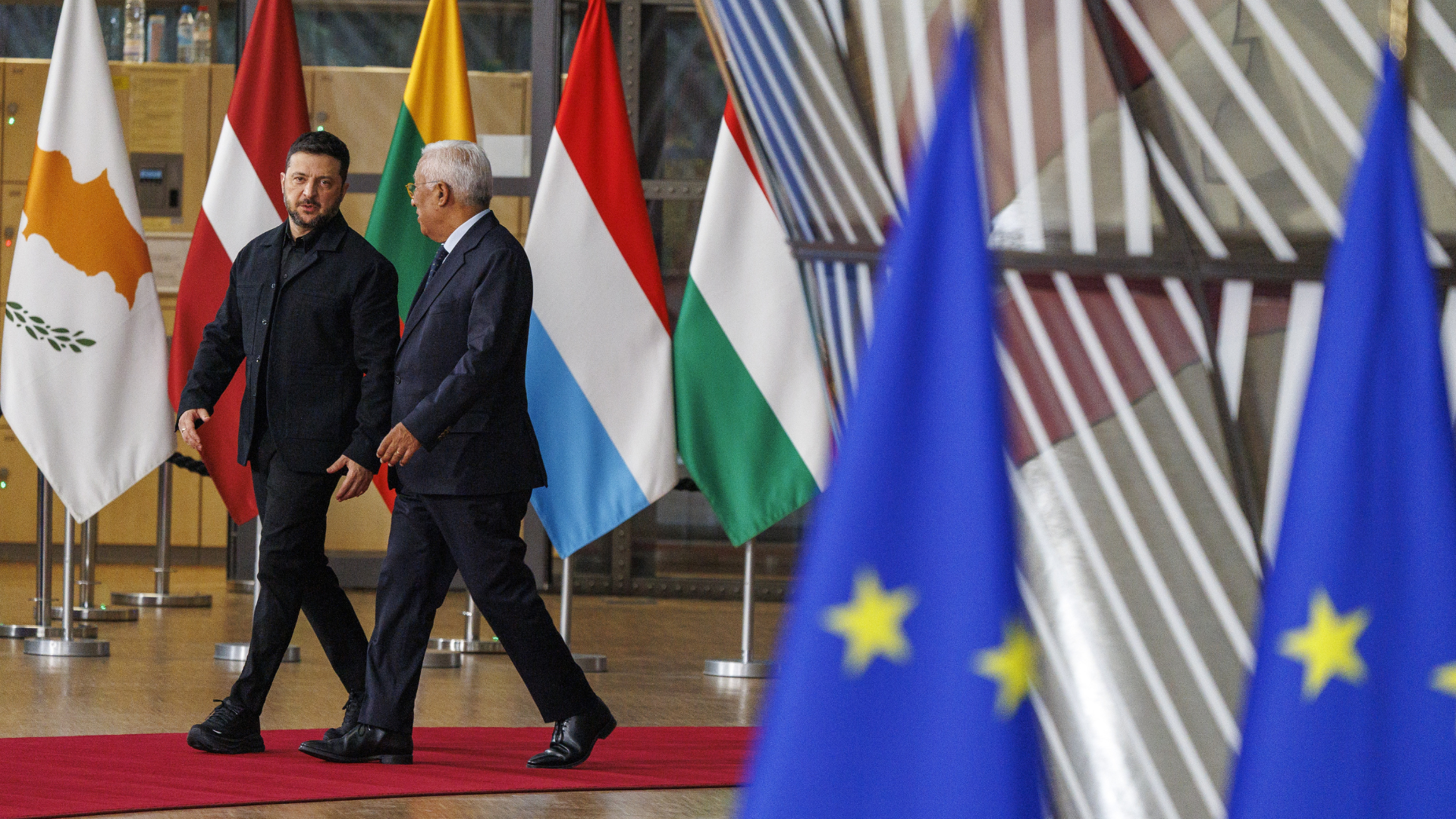

Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky and European Council President António Costa pictured ahead of a European council summit (23-24/10), in Brussels, Thursday 23 October 2025. Credit: Belga

Whether it involves two mayors in the Sahel searching for what unites their communities, or societies where online debates about Israel and Gaza are becoming increasingly heated and polarised, responsible leadership does not look away or censor opinions. Instead, it prioritises fostering constructive dialogue.

Isolation is never the solution; dialogue is. Peacebuilding is daily, patient work that is grounded in open conversations, difficult choices, and a willingness to understand other perspectives. It takes courage, and leaders must set the example.

In 2026, the world needs more than weapons and force; it needs patience and the willingness to listen. Choosing words over weapons involves risks and frustrations, but it remains both the hardest and the only sustainable, path to peace.

Hilde Deman is the Executive Director for Search for Common Ground, a Brussels-based NGO working in conflict prevention around the world.