By European standards, Belgium is a young country – a 19th-century creation – but there are some places in Brussels where you get a fascinating glimpse of what was here before.

The Palais des Académies, which stands at the south-east corner of the Parc de Bruxelles, is one such place. The building itself is a reminder of a road not taken – union with the Netherlands – and its current occupants - the academies – are a reminder of how Belgium grew out of the Enlightenment, the intellectual revolution that transformed European society during the 18th century.

The Académie Royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, which is the oldest of the institutions in the palace, began when the southern Netherlands were still under Austrian rule as l’Académie impériale et royale des sciences et belles-lettres de Bruxelles. In 1772, when Maria Theresa, the Habsburg empress, gave her imperial imprimatur to a literary society that had been set up in Brussels three years earlier, she was encouraging the city to follow a pattern established across the continent.

Royal Academies of Belgium

In London, the English Royal Society for the Improving of Natural Knowledge was set up by private individuals in 1660 and received a royal charter in 1662. In Paris, the finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert set up l’Académie des Sciences in 1666, with the specific purpose of advising Louis XIV and his ministers. In Prussia in 1700, the Berlin Academy was modelled on the French model, then revamped by Frederick the Great in 1746. Peter the Great set up an Academy of Sciences in St Petersburg in 1725. The Swedish Academy of Sciences, begun in 1739, followed the London model in that it was financed by its members and less reliant on royal patronage.

When Maria Theresa set up an academy in Brussels, she was pursuing a top-down approach (in the more commercially advanced Austrian Netherlands rather than in the heartland of the Austrian-Hungarian empire), seeing economic advantages in the application of advances in knowledge about humans and the natural world around them.

The term “academy” has its origin in a park of that name in Athens, where Plato established a school to train public servants in the 4th century BC. Plato had argued that the best constitution was the rule of the expert, and his ideas still had influence in 18th century Europe as the philosophes of the Enlightenment offered their expertise for public service.

Maria Theresa’s Académie impériale in Brussels was created in this spirit – as an élite circle of savants who were to identify the important questions warranting research, to carry out that research and to debate the conclusions: empirical observation and group discussion were a feature of the Enlightenment approach.

Imperial legacy

The Académie proved to be one of the more enduring legacies of Maria Theresa’s rule in Brussels. Although her eldest son Joseph II was more deeply imbued with Enlightenment thinking, his zeal for administrative reform provoked revolt in the Austrian Netherlands, which was soon caught up in the French Revolutionary Wars. While the Austrians did briefly reassert themselves from 1790-94, the Académie was effectively suspended until the southern Netherlands were liberated from French rule in 1815. It was revived with the creation of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1816, under the patronage of William I, which lasted until the Belgian revolution of 1830.

Inside hall of the Royal Academies of Belgium

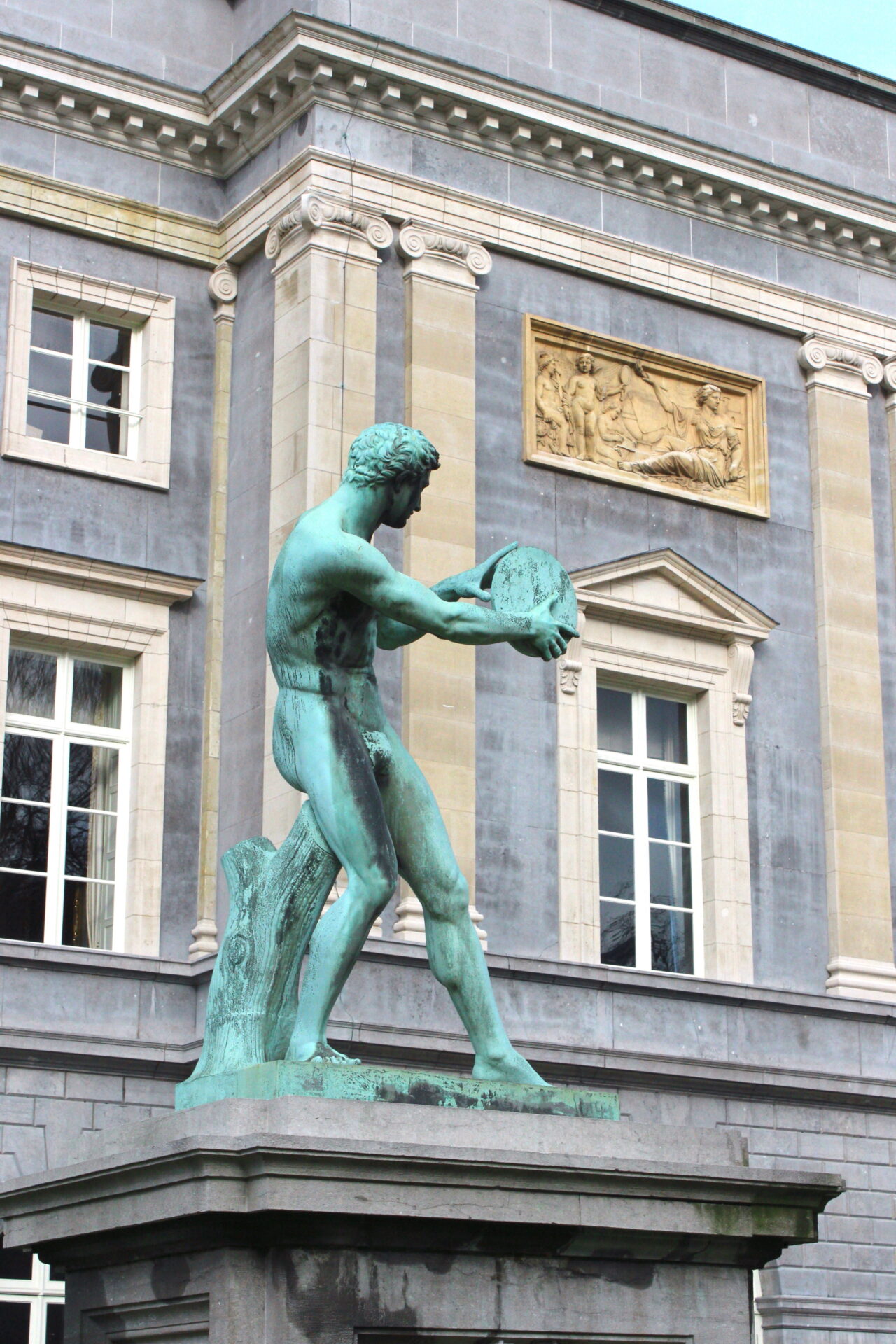

It was shortly after the creation of the Belgian state that Adolphe Quetelet, the mathematician, astronomer, statistician and general polymath, became principal administrator of the Académie. His title, secrétaire perpetuel, was adopted from the French academies and is still in use today, though nowadays the holder is limited to a five-year term, renewable once. Quetelet, whose statue is in front of the Academy today, held the office from 1834 until his death in 1874. He boosted the international standing of the Belgian institution, building its links with other academies across Europe. He was also a member of Belgium’s Royal Academy for Medicine, which was established in 1841.

One of the projects that Quetelet was much involved in was a Belgian dictionary of national biography, for which the academy received a royal mandate in 1845. It was a huge task: The first volume, covering surnames from AA to Baudet, appeared in 1866 and it took until 1938 to reach the end of the alphabet (supplements followed until 1986).

French first

Those volumes were published only in French, and for most of the 19th century, it went largely unquestioned that the Académie royale was francophone: French was the language of the social and intellectual élite in both the south and north of the country. But it was symptomatic of growing Flemish linguistic identity when, in 1886, an academy for Flemish language and literature was established in Ghent. One of its aims was - unsurprisingly - to promote writing in Flemish, the volkstaal, but it also had an objective of developing scientific knowledge in Flemish, so its membership included not just writers and critics, but experts from other academic disciplines.

But as Flemish identity became more assertive, in the 1920s and 1930s, the pressure built up for a Flemish academy of arts and sciences. The idea received royal approval in 1938 as the Koninklijke Vlaamse Academie voor Wetenschappen, Letteren en Schone Kunsten, which was established during the Second World War in the Palais des Académies. Likewise, a Flemish academy of medicine was set up at the same time.

Meanwhile, the Belgian francophone world had taken a step in the other direction, creating in 1920 a separate Académie royale de langue et littérature françaises de Belgique, at the instigation of the then minister for science and arts, Paul Destrée (and so sometimes known as la Destréenne). It took its inspiration from l’Académie francaise in Paris, though in two respects it was more inclusive: women were admitted from the beginning, and non-Belgians were a quarter of the 40-strong membership. The balance between writers and philologists was struck at two-thirds to one-third.

Statue of Discobolus by Mathieu Kessels (1867)

Another in Belgium’s galaxy of royal academies had its origins in the 1920s. L’Institut royal colonial belge was set up in 1928, in part to get Belgian students interested in the colonies and to encourage scientific work there. Its membership was a mix of politicians, business people and academics, split into three classes: one on natural sciences and medicine, one on technical science (including energy, transport and geology), and another on more political and commercial matters – effectively colonial policy. Each class had 15 members with 30 associate members from Belgium or overseas. In 1954, this was renamed the Royal Academy of Colonial Sciences and renamed again four years later – such was the tumult of the period – the Royal Academy of Overseas Sciences.

But for the first two decades after the Second World War, there was a strange asymmetry about the biggest academies: there was a national academy for sciences, letters and arts – sometimes referred to, because of its Habsburg origins, as “la Thérésienne” - and a Flemish academy for sciences and arts.

The asymmetry was resolved by the linguistic and constitutional reforms of the 1970s and 1980s that saw cultural councils created for the different linguistic groups and given devolved decision-making powers over culture. La Thérésienne was taken under the wing of the francophone community – a counterpart to the Flemish academy, albeit without a linguistic/cultural identifier in its name (the same thing happened with the medical and literary academies). Thereafter, the scientific academies each received financial support from their respective communities.

Until this year, when the Flemish region stopped providing core funding for the Royal Flemish Academy for Science and Arts. The loss of about €750,000 a year has created, says the academy, “an existential crisis”.

Political role

The academies had seemed, for a long time, a fixed feature of Belgian society, at the juncture of the academic and political worlds. Politically, though, élites are now deeply unfashionable - suspect even - in an era of shrinking budgets and growing populism. The essential business of the academies – common to them all – has over the decades been publication of specialist academic journals and awarding prizes – sometimes with accompanying competitions – to encourage and reward research.

But such activities are, by their nature, intended for specialist readerships and audiences. In some lights, the academies, when they debate organisation of their disciplines, look similar to the guilds of medieval times, who claimed to uphold the standards of their trade, but often did so while excluding alien outsiders.

Although in recent decades, the academies have been looking to enlarge their audiences with public lecture series, they are competing for attention with many others – the universities themselves, museums, art galleries and all kinds of media. The Flemish Academy of Language and Literature embarked on a project of defining – and redefining - a Flemish literary canon, but Flemish cultural identity is now sufficiently established for ministers to make hard budgetary choices, as the museum sector is finding out. The academies are not the only cultural institutions feeling the budgetary scalpel.

The open letter submitted by the Flemish Academy for Science and Arts to the Flemish government argues that: “Just now, in an age of disinformation, technological revolutions and geopolitical uncertainty, investment in knowledge is of vital importance.” That argument can be heard echoed across Belgian universities where the shockwaves are felt from the Trump administration’s various assaults on academic freedom.

The Royal Academy for Overseas Sciences, which remained a federal rather than regional responsibility and nowadays promotes international science co-operation, is now under the wing of the Royal Observatory at Uccle. So whether public funding for Belgium’s academies will survive is to be tested in three different crucibles: Flanders, Walloon-Brussels community, and the federal.

The model has remained remarkably durable since the days of the Habsburg empire, but whether it will survive is not guaranteed. The philosophes of the Enlightenment, convinced of the merits of critical thinking, argued to their rulers that scientific and technological discovery could improve the happiness of individuals and the well-being of society. The current fragility of Belgium’s academies is a sign that we live in age that is equally sceptical but much less confident.

Related News

- How Belgium’s railways fuelled the Nazi war machine

- How the Art Nouveau soul of Brussels was saved

- What is Brussels 'zwanze'?

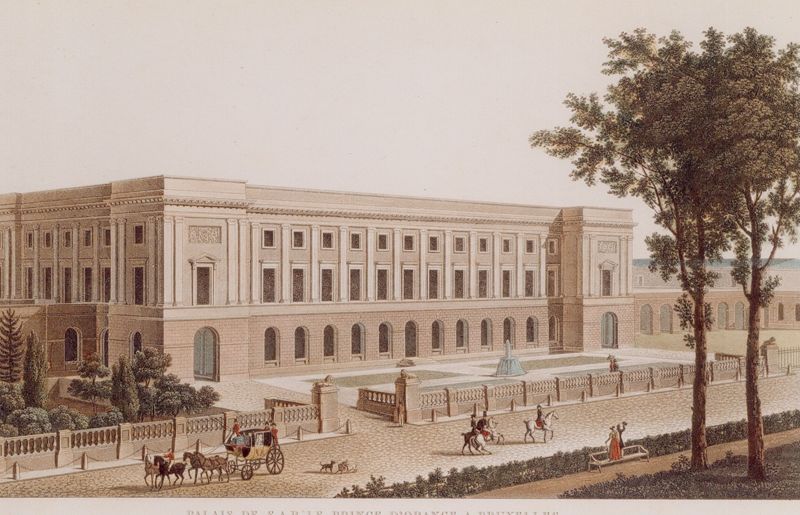

Old image of the Royal Academies of Belgium

A failed kingdom in stone: How one grand building reveals Belgium’s prehistory

The Palace of the Academies, which is now home to most of Belgium’s academies, is also a monument to what might have been. It is a remnant of an experiment in state-making that failed: the United Kingdom of the Netherlands.

The Palace was built as the home of William, Prince of Orange, the heir to the Dutch throne. William’s father, William Frederick, had been installed as William I, the first king of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands – his own father had been the last stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, forced into exile in London in 1795 as the French revolutionary army invaded his territory.

After Napoleon and the French army had been defeated at the Battle of Leipzig in 1814, and then again at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the victorious great powers – Britain, Prussia, Russia, Austria - sought during the Congress of Vienna to contain France and also each other’s own competing interests. The British pressed for buffer states on the border with France: a United Kingdom of the Netherlands, then continuing south with Switzerland and Savoy.

The Great Powers were putting back together what had previously broken apart in 1581, when the provinces of the northern Netherlands had successfully rebelled against Spanish rule. Their southern neighbours, which included the Flanders and Brabant territories, were reconquered and remained part of the Spanish (later the Austrian) Netherlands until 1790, when, in the wake of the French Revolution, they rebelled against Habsburg rule, were briefly independent and then occupied by the French.

William’s pile

William, Prince of Orange, who as a 22-year-old had fought in the Allied army at the Battles of Quatre Bras and Waterloo, was, in the early days of the new kingdom, something of a Brussels favourite. The States-General offered him a palace in Brussels and a hunting pavilion at Tervuren. It is the former, constructed in the mid-1820s, which now houses the Belgian academies. It stands today between the inner ring-road and the Brussels Park (Parc de Bruxelles, Warandepark) at the corner closest to the Trone metro station (from the end of Rue Montoyer, where it meets the inner ring road, one can see that the centre of the palace is aligned with Montoyer).

It is the work of the Brussels architect, Charles Vander Straeten, who was appointed by William I to work on royal and state projects, and whose work included the Dutch monument at the Waterloo battlefield, the Lion’s Mound. At the same time the new palace was built, William I had a royal palace created for his own use, by converting two mansions. This latter building, neo-classical in style, has since made way for the current Royal Palace, which largely dates from Leopold II’s reign, with all the excess that habitually entailed.

The nearby palace of the Prince of Orange was primarily a family home for the heir to the Dutch throne. It was built in a sober, neoclassical style, with the front and back facades of the palace identical. Inside, there is more symmetry, particularly with the arrangements of the rooms along the length of the eastern side.

Old image of the building which today is the Royal Academies of Belgium

The various uses made of the building since the mid-19th century have left their mark, obliterating some of the classical features, but also creating some impressive reception rooms. It was serving as an art gallery before the decision was made in 1876 to move the academies from their previous home in the palais de Charles de Lorraine. The academies themselves have left their mark: in 1966, the neighbouring stable block was acquired and converted to house the academies’ library collections. The entirety is worth a visit during one of the city’s regular heritage days.

Such visits have a surprisingly long history. In the wake of the Belgian Revolution of 1830, the Prince of Orange and his family left the palace, which they had lived in only since 1825 (they had previously had a house in Rue de la Loi), and it was sequestrated by the Belgian state. Only in 1839, after protracted wrangling between Belgium and the Dutch sovereign, were the Dutch royal family granted compensation and permission to recover their furniture. But as early as 1832, visitors were being given tours around the palace.

That the settlement with the Dutch royal family took so long is an indication that the birth of the new Belgian state was not straightforward. The London Conference of 1831 had recognised Belgian independence, but William I held out for a revised settlement that in 1839 saw Belgium lose parts of the provinces of Limburg and Luxembourg – and oblige it to pay compensation for the sequestrated royal property.

Failed experiment

Historians still debate whether the United Kingdom of the Netherlands was doomed to failure from the start because of cultural, religious and economic differences between north and south.

Might the kingdom have survived had William I not so aggressively demanded that the south assimilate both on language and religion to the ways of the Dutch-speaking and Protestant north? If the more commercially advanced south had been less heavily taxed, would the liberal bourgeoisie still have allied with the Catholic church? How might supporters of the House of Orange have played things differently? Or were these short-term tactical failures irrelevant compared to the longer-term divergences?

Such historical debates are never-ending, but they attract particular attention in Belgium because, during the long struggle for Flemish linguistic identity, the idea of uniting with the Dutch-speaking neighbours has resurfaced repeatedly. The Palace of the Academies is a gentle reminder, to those who protest that the state of Belgium is an artificial construction, that other constructions have been tried - and have, for whatever reason, failed.

The latest edition of The Brussels Times Magazine is in shops now!