He’s mostly known today for the boulevard he gave his name to, but as the US’s ‘Minister’ in Belgium during the First World War, Brand Whitlock was ensured aid reached millions who risked starvation from the blockades. A former mayor of Toledo and prolific writer, Whitlock’s wartime heroics earned him the thanks of the grateful Belgian nation, as Dennis Abbott reports

Say “Brand Whitlock” to most people in Brussels and chances are you’ll get directions to a noisy dual carriageway that leads from the notorious Square Montgomery rush-hour bottleneck to the Art Deco enclave of Square Vergote, where Schaerbeek and Woluwé-Saint-Lambert meet, close to the E40 motorway access.

Originally Boulevard de Grande Ceinture, the thoroughfare was renamed Boulevard Brand Whitlock by the conseil communal on March 6, 1915, to honour a US First World War hero. Today, Whitlock is largely forgotten, in both his homeland and Belgium. So, who was he?

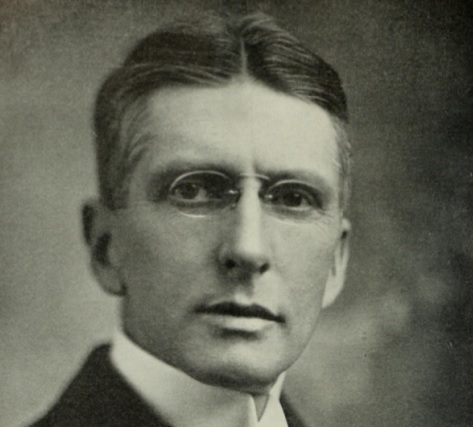

Joseph Brand Whitlock was a journalist, author, politician and diplomat. Born on March 4, 1869 in Urbana, Ohio, to the Reverend Elias D. Whitlock, a Methodist minister, and Mallie Brand, he had two younger siblings, Mary, who died aged 11, and Francis, a brother who also pre-deceased him.

After leaving school, Whitlock passed up on university. He headed instead for the port city of Toledo on Lake Erie, where he cut his teeth as a cub reporter on newspapers including The Toledo Blade. In 1891, he moved to The Chicago Herald, where he covered politics and baseball. He caught the eye of Illinois Governor John P. Altgeld who asked Whitlock to work for him in the state capital, Springfield, where he also studied law under Senator John Palmer, a Civil War general in the Union army.

It was in Springfield that Whitlock met his first wife, Susan Brainerd. She died, aged 18, four months after their wedding in 1892. Whitlock married her sister Ella, known as Nell, three years later. They were inseparable for the rest of his life.

Whitlock quickly made his mark as a lawyer. In 1893, he drew up an appeal for three men convicted of involvement in a bomb attack that left 11 dead, including seven police, at a Chicago workers’ rally. Samuel Fielden, a British-born Methodist pastor, and two other men from immigrant backgrounds, Michael Schwab and Oscar Neebe, were found guilty of conspiracy. Governor Altgeld, himself a German immigrant, granted Whitlock’s appeal, signing pardons for the three. Four co-defendants were less fortunate and hanged.

Four-time mayor of Toledo

Whitlock returned to Toledo to set up his own legal practice in 1896. He was a supporter of the city’s popular Welsh-born mayor, Samuel ‘Golden Rule’ Jones, whose nickname referred to his business motto: “The golden rule: Do unto others as you would do unto yourself”. When Jones died unexpectedly in 1904, Whitlock ran for mayor, vowing to continue his predecessor’s social reforms such as free kindergartens and an eight-hour working day. Whitlock was elected for four consecutive terms from 1905 to 1913. He twice introduced bills to abolish the death penalty in Ohio, but both failed.

Three mayors: H.T. Hunt of Cincinnati, Brand Whitlock of Toldeo, Newton Baker of Cleveland

In parallel with his political career, Whitlock was a prolific writer, churning out novels, non-fiction and magazine articles. His work often focused on political and social issues, with thinly veiled autobiographical content.

His 1902 debut, ‘The Thirteenth District’, the story of the rise and fall of a congressman, was an instant success. ‘The Happy Average’, about a young lawyer, and ‘Her Infinite Variety’, supporting the vote for women, appeared in 1904. ‘The Turn of the Balance’, a critique of the judicial system, published three years later, was hailed by Call of the Wild author Jack London as “a splendid book [which] displays a noble and sympathetic understanding of society.” Whitlock followed it with a biography of Abraham Lincoln.

After his fourth term ended in 1913, Whitlock decided to focus on his writing. He was 44 and putting the final touches to his autobiography, ‘Forty Years of It’. His friends, however, urged the new US President, the progressive Woodrow Wilson, to find Whitlock a position. In December 1913, Wilson appointed him Minister to Belgium, a minor diplomatic posting but perfect for Whitlock who saw the country as a quiet backwater where he could absorb European culture and write.

Diplomatic idyll

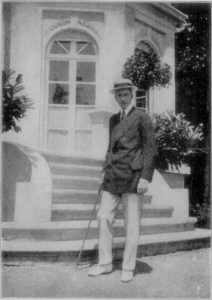

He quickly embraced the diplomatic lifestyle, enjoying long luncheons, receptions, nights at the opera and chauffeur-driven cars. He found a pleasant villa, Bois-Fleuri, at Quatre-Bras, near the top of Avenue de Tervuren. An oasis of peace – there was no ring road then – it was handy for Ravenstein golf course, as much a favourite with diplomats then as today.

Brand Whitlock in front of his villa in Brussels

Whitlock was at his villa when he first heard of the assassination of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie by a Bosnian Serb student, Gavrilo Princip, on June 28, 1914. Whitlock barely paid attention to the incident, assuming it was a local issue that would soon be resolved. He was more interested in the trial of Henriette Caillaux, the socialite second wife of France’s ex-Prime Minister Joseph Caillaux, who had shot and killed Le Figaro editor Gaston Calmette after he published her love letters (the jury decided it was an unpremeditated crime of passion and acquitted her).

Even when Germany backed Austria against Serbia, few thought the situation would escalate. “Life went on quite the same. The Legation was quiet, deserted, dull. [US Secretary Hugh] Gibson and I strolled down to the Caveau de Paris, the little restaurant in the Rue du Marché aux Herbes, where diplomats were always to be found at noon,” wrote Whitlock.

Instead, the 1914 ‘July Crisis’ triggered a seemingly unstoppable sequence of events, all recorded by Whitlock in a daily journal which would later form the basis of his wartime account, ‘Belgium, A Personal Narrative’. Russia backed Serbia and mobilised on July 30. Germany declared war on Russia. France, allied with Russia and Britain in the Triple Entente, mobilised on August 2. The same day, Claus von Below-Saleske, Germany’s envoy in Brussels, delivered an ultimatum to Belgium’s Foreign Minister Julien Davignon, demanding free passage for the Kaiser’s army.

“To the Belgian ministers, the summons to let the German troops pass over Belgian soil to attack France came as a blow that was not diminished in its force by the fact that it was not unexpected. It seemed, indeed, but a detail in the midst of those tremendous events that were tumbled each moment, into the horrid chaos of the world,” wrote Whitlock.

Belgian defiance

The American was present when Belgium’s King Albert addressed the Parliament on August 4. “[It is] a scene one would not soon forget,” recalled Whitlock. As the sovereign entered, the room erupted in cries of “Vive le Roí!” Wearing his general’s uniform, his sabre clanking at his side, the King asked: “Are you unwavering in your determination to keep the sacred heritage of our ancestors intact?”

“Oui, oui, oui!” the deputies and senators roared in unison. “I find myself leaning over the balcony rail, a catch in my throat, my eyes moist,” Whitlock wrote.

The US Legation, on the corner of Rue Belliard and Rue de Trèves, was besieged by panicking US citizens, pouring into Brussels from all over the continent. “In many instances, the women are calmer, braver than the men,” Whitlock observed. He immediately expanded his team, securing the services of Gaston de Levai, a lawyer, and Caroline Larner, a State Department official who was in Brussels at the wrong time.

As the representative of a neutral country, Whitlock was asked to take over consular operations for Britain, France, Denmark, Austria-Hungary, Japan and Germany, whose 60,000 expats were also in a panic to leave. Several thousand were put on a cattle train at Gare du Nord, among them a frightened 13-year-old girl, Magda Behrend, from the Ursuline Convent of Virgo Fidelis in Vilvoorde. She later would become the wife of Joseph Goebbels.

German troops crossed the frontier on August 4. The Belgians put up a brave defence, holding out for longer than the Germans expected. Liege finally fell on August 16 and the government abandoned Brussels. The Belgian army withdrew to Antwerp and then the Yser where it halted the enemy by opening sluice gates to flood the plain.

Fear of attacks by armed civilians, francs-tireurs as they were known, resulted in the invaders adopting a policy of terror, Schrecklichkeit. The summary executions, use of human shields and indiscriminate torching of towns became known as the ‘Rape of Belgium’. On August 25-26, German troops burnt down the university library in Leuven, destroying 230,000 books and a thousand precious manuscripts.

Emergency relief for millions

Up to three-quarters of Belgium’s food was imported and supplies quickly ran low. Border closures and the Allied blockade meant many began to starve. The Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB), founded by future US President Herbert Hoover, raised $1 billion and shipped five million tonnes of food, feeding nearly 10 million people in Belgium and, later, in northern France.

Whitlock played a critical role in persuading the German authorities to allow the food to get through to those in need. He worked closely with the Comité National de Secours et d’Alimentation, supported by Belgian business leaders such as Ernest Solvay, Dannie Heineman and Émile Francqui.

In addition to food aid, the CRB set up job schemes. The lace-making sector, which employed 50,000 women before the war, was badly hit. Irone Hare, the US-born Viscountess de Beughem de Houtem, persuaded Hoover to send thread on the boats bringing flour. As president of the Comité de la dentelle, Nell Whitlock was ideally placed to support her friend.

Brand Whitlock’s unstinting work to secure food supplies and his appeals for condemned Belgians earned him the sobriquet Le Ministre Protecteur. He could not, however, save the British nurse Edith Cavell, sentenced to death for helping British and French soldiers to escape. Despite being bedridden with illness, Whitlock wrote to the German governor, Baron Oscar von der Lancken, underlining that Cavell “had bestowed her care as freely on the German soldiers as on others”. The letter was hand-delivered by Gibson, de Levai, and the Spanish Minister, the Marques de Villalobar, who also begged the governor to show mercy.

It was to no avail. Cavell was shot at dawn at the Tir National in Schaerbeek on October 12, 1915, alongside a Belgian architect, Philippe Baucq. Cavell’s execution received worldwide condemnation and her stoicism (“Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness,” she told Anglican chaplain H. Stirling Gahan) was exploited in British propaganda. Her death and the sinking of the Lusitania, torpedoed with the loss of 1,198 passengers and crew, 128 Americans among them, hardened US attitudes.

America increasingly supported the allied war effort with materials and loans to buy munitions. Germany’s promise to help Mexico regain its old territory was the final straw. The US entered the war on December 17, 1917 and Whitlock had to leave Belgium. Before his departure, he negotiated for neutral Dutch and Spanish officials to continue the CRB food aid programme. He accompanied compatriots to Switzerland, before moving to Le Havre to be close to the Belgian government-in-exile.

Post-war return

After the Armistice, the Whitlocks returned to Brussels, arriving in time to witness the royal entry on November 22, 1918, when King Albert rode through the city, accompanied by the Queen and Britain’s Prince Albert, the future George VI.

Brand and Nell Whitlock visiting a camp where US soldiers guard German prisoners at Chateau-Thierry, France. Whitlock in the middle, wearing a top hat.

Life gradually returned to normal. Whitlock welcomed President Woodrow Wilson to Belgium on June 18, 1919. Wilson, driven personally by the King at breakneck speeds, visited Ypres, Nieuwpoort, Diksmuide and Ostend.

The President proposed the Legation in Belgium should be raised to an embassy and nominated Whitlock as its first Ambassador. One of his first duties was accompanying the Belgian royals on a month-long US tour in October 1919.

Boulevard Brand Whitlock in Brussels.

Whitlock’s tenure as Ambassador was short. Warren G. Harding won the Presidency in 1920 and, as a Wilson appointee, Whitlock had to resign.

On July 28, 1921, he was a guest at the laying of the foundation stone of the new university library in Leuven. Attendees included the King, French Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré and Marshal Phillipe Pétain, the lion of Verdun who would later serve as President of Vichy France. The library replenished its collection with donations from all over the world. Sadly, it was wrecked again during another German invasion in May 1940.

For the rest of his life, Whitlock and his wife lived in Europe, mostly near Cannes. According to Edward and Libby Klekowski, authors of Americans in Occupied Belgium 1914-1918, Whitlock never adjusted to post-war America. “In his view, it had become the land of philistinism and of prohibition. The couple became part of the American expatriate colony: winter in Cannes, spring or fall in Brussels or Paris, summer at Vichy, always living in hotels, always writing.”

Between 1923 and 1933, Whitlock published seven more novels and a biography of Lafayette, the French aristocrat who fought in the American War of Independence. To Whitlock’s consternation, his later books received only lukewarm reviews.

He suffered frequent bouts of ill health. The New York Times reported on December 4, 1932, that Whitlock was being treated for shingles. On March 5, 1934, he entered the Sunnybank British-American hospital in Cannes for an operation on an enlarged prostate. Friends thought he was recovering, but he soon needed further surgery. Whitlock died on May 24, with devoted Nell at his bedside. He was 65.

Reporting on his passing, the Associated Press described Whitlock as an “outstanding world war figure” whose “vigorous efforts on behalf of the Belgian civilians in the face of strong opposition by the German military leaders won for him the admiration and affections of the Belgians, to a degree only slightly less than their love for their fighting king.”

| Whitlock’s literary journey Brand Whitlock wrote dozens of short stories, published in magazine titles such as The Reader, American Magazine, The Saturday Evening Post. The Philadelphia-based Post, the lavishly illustrated and most popular magazine in the US in its early 20th century heyday under editor George Horace Lorimer, regularly featured Whitlock’s work. It published one of his earliest short stories, The Finals and Alice Gray, on March 21, 1903, as well as one of his last works, The Place At Table, on August 13, 1932. The latter focuses on the world of diplomacy and an envoy who is infuriated when a rival deliberately seats him in a place which, he feels, does not accord with his rank. Whitlock almost certainly witnessed the sensitivities aroused by seating plans during his time in Brussels – though there is no hint he was personally snubbed in this way. The story is illustrated by Henry Raleigh, the most fashionable society artist of his day and a friend of F. Scott Fitzgerald, author of The Great Gatsby. Brand Whitlock, whose short stories were compiled in two books, fell out of fashion after the war and found it increasingly hard to win magazine commissions. Former associates felt his writing style had changed and become too highbrow. An article by Joyce Chenoweth entitled Like the Brand Whitlock We Once Knew? Hell, No, published in The Indiana University Bookman in 1967, includes excerpts from letters exchanged in 1924 between two of Whitlock’s former editors, De Wolff and Howland, from his pre-war publisher, Bobbs-Merrill. De Wolff, comparing his early writing with his post-war output, comments: “Brand Whitlock was writing real stuff, as he did in The Thirteenth District. No straining for effect, no plain attempt to use big words, no ‘titivation’, no ‘ineluctable’, no ‘exiguous’, as show up in the new preface – just plain English. In his last novel, J. Hardin & Son, I picked up a list of 100 words of that class that, I believe, not one in a thousand would understand.” Howland replies: “You are dead right about Brand, I’m afraid. Between us, Belgium has worked an amazing change in him. He has lost the common touch, been completely de- democratized, politically, socially and literarilly [sic].” Their views might have been coloured by Whitlock’s decision to leave Bobbs-Merrill for D. Appleton & Company, which published Belgium, A Personal Narrative in 16 editions between 1919 and 1920. |