As Ukraine battles for its survival, it is also fighting for its place in the European family. Ukraine’s European heritage goes back centuries: its western connections made it the hub of the Russian Empire’s industrial revolution. And driving this transformation was a plucky group of Belgian entrepreneurs.

For much of its history, Ukraine’s identity as a distinct nation has been overlooked. It has spent long periods locked into other empires, and even today, some still claim Ukraine is merely a by-product of Russia’s glorious story.

This line is repeated when it comes to Ukraine’s industrialisation: during the Soviet era, the myth emerged that the Bolsheviks, who came to power in 1917, industrialised the former empire of the Russian tsars.

The reality, however, is far more exciting. Ukraine’s industrialisation preceded the Soviet era by many decades and was largely driven by Europeans and American entrepreneurs. And Belgians led the pack.

Indeed, the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine was the industrial heart of the Russian Empire in the second half of the 19th century. The rush to Donbas was sparked by the discovery of iron ore and coal deposits in the region, a scramble that was likened to the California gold rush three decades earlier.

Western European money then turned Donbas into an industrial powerhouse. Brokers brought not only the technology but business skills, banking connections and the spirit of capitalist entrepreneurship. Investors from Belgium, France, Britain, Germany, Switzerland and the United States flooded to the region. The explosive growth of the Donbas during this period prompted Russian author Alexander Blok to dub the region ‘New America’.

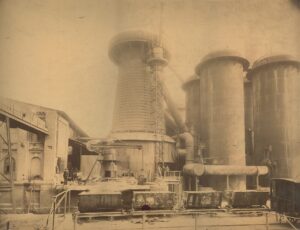

The Dniprovskiy steel plant

Why did these outsiders settle so easily into the Donbas? To answer that, we need to go further back into history. For centuries, the Donbas was part of the ‘Wild Fields’, a vast swathe of sparsely populated borderlands stretching across the Ukrainian steppe that split the Slavic states to the north from the Ottoman Empire to the south.

When Russian Empress Catherine the Great offered land grants to entice newcomers in the 18th century, it brought waves of settler migration: Ukrainians, of course, but also large numbers of Russians, Romanians, Serbians, Hungarians, and Germans as well as ethnic Greeks from nearby Crimea. This helped to make the Donbas region one of the most cosmopolitan corners of the Russian Empire - and receptive to western European influences.

Belgium takes the lead

Belgians led the industrial transformation in the region. Belgium itself was one of the first countries in the world to industrialise after Britain, developing vital iron, coal, textile and rail services. Eventually, the country’s entrepreneurial zeal would spread further afield: when coal and iron were discovered in the region, Belgian business leaders decided to replicate some of their domestic successes in Ukraine.

The first Belgian businesses in the region were horse-drawn trams in Odesa (1880) and Kharkiv (1883). In the 1890s Belgium became the first country to create an entire network of coal and steel enterprises, a unified system of rail connections, and even the newest fittings. Belgian investors put 550 million gold francs in the Donbas, which would be more than €5.5 billion in today’s money.

Belgian interest in Ukraine was concentrated in the Prydniprovsky-Donetsk region. The Donetsk Basin was known as the ‘Tenth Belgian Province’. In 1897, 576 Belgians were working in the region, but after that, their numbers rose by 2,000 every year. They included engineers, craftsmen, managers, doctors, teachers and family members.

By 1914, 31 Belgian companies were operating there: 10 in iron, steel and other metals, seven in the mining (24 individual coalmines belonged to Belgian entrepreneurs), six building trams, and five producing construction materials and glass.

The most intense industrial activity in the region centred on Dnipro, at the time known as Katerynoslav or Ekaterinoslav. There were 48 Belgian joint-stock companies in Katerynoslav. The largest of these was the gigantic South-Russian Dnipro Metallurgical Society created by two powerful industrial corporations, Poland’s Lilpop, Rau and Loevenstein, and Belgium’s John Cockerill & Cie.

The Dniprovskiy Steel Plant, which was 90% Belgian-owned, was a showpiece of Tsarist industrial achievement when it opened in 1886. Two brothers from Liege, Charles and George Chaudoir, set up a joint-stock company in 1889 and rapidly developed three large pipe-rolling factories in Katerynoslav.

Train wheels made at the Dniprovskiy steel plant

Russian journalist Volodymyr Giliarovsky wrote excitedly after a visit to Katerynoslav in 1899: “Foreigners are going to Russia with huge capital! The Belgians are already the main hosts in southern Russia. People there say the best mines and ironworks are in Belgian hands throughout the Dnipro region. On the train, you can only hear: ‘Ore, coal, pits, prospecting, the Belgians…’”

Further east, in Kostiantynivka, Louis Lambert, Paul Noble, and Joseph Siesel set up the Anonymous Society of Donetsk Glassworks. Nearby, the Bunge Mine, named after Andrey Bunge, was founded in 1908 by the Société métallurgique Russo-Belge (when it later fell under Soviet control, it was renamed Yunkom, and in 1979 was used for an underground nuclear explosion).

Much of Kostyantynivka was built by Belgians, and it still boasts a few Belgian architectural monuments from those times. In the Luhansk city of Lysychansk, Belgian chemicals pioneer Ernest Solvay built the Donetsk Soda Plant in 1895 with a merchant from Perm called Ivan Lyubimov producing soda ash and other chemicals.

Brussels-Dnipro rail link

The Belgian connection was strengthened in 1897 with the creation of the Katerynoslav City Railroad joint-stock company, which was behind Dnipro’s first electric tram services. A huge novelty at the time, the tram remains central to the city’s public transport network today. Belgian companies would also build tram services in other Ukrainian cities including Kyiv, Kremenchuk, Sevastopol and Odesa. Tram building eventually became the second most profitable for Belgian companies in Ukraine after iron and steel.

As the Belgian presence grew, a railway link connected Brussels to Dnipro. Known as the Nord Express, it entered service in 1896 and had a total journey time of 65 hours, including a change of trains in Warsaw.

Odessa's tramline

Before the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, there were a total of eight Belgian consulates in today’s Ukraine: in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Berdyansk, Dnipro, Mykolaiv, Mariupol, Odesa and Sevastopol.

Belgians were not the only western Europeans in the Donbas. While they were based around the so-called "Belgian province" with its centre in the city of Luhansk, the "German land" was in the south of Donetsk Region, the "French region" in its eastern part, while the "English region" was in Donetsk, which is now the largest city in the Donbas. Welsh ironmaster John Hughes founded a settlement that was originally named Hughesovka or Yuzivka in his honour that later became Stalino before being renamed Donetsk, which is now the biggest city in the Donbas.

Severed connections

However, the connections would be severed after the 1917 Russian Revolution: when the Bolsheviks seized power, they quickly seized all private enterprises and saw any businessman as an enemy of the proletariat. Belgium’s role in Ukraine’s earlier industrialisation was whitewashed and the Kremlin claimed credit for itself, Communism and the proletariat.

Later waves of Stalinist repression in the 1930s drove non-Russian ethnic groups from the Donbas: mainly Ukrainian, but also the region’s Greek, German and Polish communities. Ukrainian, Greek, German, and other European place names disappeared from the Donbas and were replaced by generic Soviet alternatives. It was one of the reasons why Belgium only recognized the Soviet regime in 1935.

However, the Soviets proved poor industrial managers. By the time the Soviet Union was dissolved in 1991, Donbas was a backward region with loss-making production. Today, most of its factories still use equipment installed at the end of the 19th century.

As for the Belgian legacy in the Donbas, it is hard to locate. The industrialists and settlers left few notable buildings or monuments, only a handful of houses and the ruins of old industrial installations. In February 2018, the architecture of Lysychansk, home of the Solvay soda plant, received the Belgian Heritage Abroad Award, but not many remnants remain.

But they were there. Belgians and the other western Europeans played a vital role in Ukraine’s story. And as Ukraine fights for its survival and its identity, this industrial heritage shows our deep European connections.