On this day, 29 March 1886, the first major workers' revolt in industrial Belgium ended after 11 days of violent insurrection by factory workers. Also known as the Belgian strike of 1886, the revolt took place in the industrial provinces of Liège, Hainaut and Namur, and would change the country's history forever.

As one of the first countries to industrialise after Great Britain in Europe, Belgium in 1886 was ravaged by social inequality. It had been suffering the effects of a serious economic crisis: a sharp drop in wages, widespread unemployment, a 13-hour day for those lucky enough to have work, and a lack of labour legislation or social support.

The sizeable yet largely exploited worker base was facing increasing precariousness, spurred on by the prospect of novel industrial revolution-era machinery automising their jobs. Following another harsh winter in the great depression of 1882-1885, popular frustrations within the Walloon industrial base were growing.

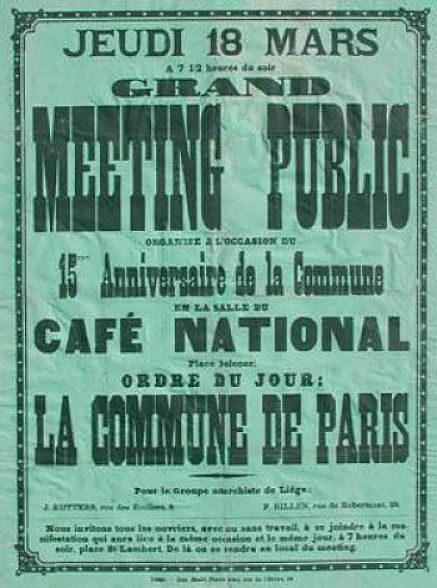

On 18 March 1886, a group of anarchists in Liège decided to organise a small demonstration to commemorate the 15th anniversary of the 1871 Paris Commune. That day, however, several thousand workers, young unemployed people and women all responded to the call. As many as 800 or 900 workers from the city’s metalworks showed up to the gathering.

The poster that began the Belgian strike of 1886. Credit: Creative Commons

The crowd shouted "Long live the Republic", “long live the Commune", “long live the worker.” The Marseillaise, a republican anthem of the time, was passionately sung by participants. After marching throughout the city, that evening people demonstrated on the Place Saint-Lambert in Liège. Edouard Wagener, one of the members of the anarchist group, took the floor amid palpable rising tensions, delivering an incendiary speech.

"Citizens workers, you have just passed through the richest streets in the city. What did you see? Bread, meat, wealth and clothes. Well! Who provided this? Did you? You are all starving, you have no food, you have nothing on your bodies. No! No! Well, you are cowards."

The crowd erupted. Amid confrontations and harassment by police, around 500 or so demonstrators broke out into rioting.

The fuse is lit

In less than 10 minutes, shop windows were smashed, children threw stones into shops, public property was ransacked and flaming petrol was thrown at the mounted gendarmes. The violent clashes and looting lasted all night: 17 were injured, including six from the security services, and 104 buildings were damaged. Wagener and 46 other people were arrested.

While that night ended with the authorities restoring the calm in the city, the seeds for a popular revolt had been planted.

Without any direct correlation to the events of the day before, the next day, the miners of the Charbonnage de la Concorde in Jemeppe-sur-Meuse went on strike, demanding a pay rise.

The Strike (1886) by Robert Koehler, often assumed to depict the 1886 strikes in Belgium. Credit: Creative Commons

On 20 March, the worker mobilisation reached Ougrée, Seraing, Flemalle and Tilleur. The Belgian government, panicking, mobilised the army, in an attempt to prevent more spontaneous gatherings. But the more the strikes spread, the more the violence increased.

In the days that followed, the authorities assembled reinforcements through marching platoons of the gendarmerie from Brussels, Namur, Louvain, Limburg and Luxembourg. "A real small army – flanked by artillery batteries, engineering companies and quartermaster services," according to the historian Frans van Kalken.

The strikes also spread to Belgium’s pays noir, Charleroi (named for the geological presence of coal in the area), where the turbulences would eventually take a deadly turn.

Storming of castle, violent reprisals

On 26 March, the coal mines of the Charleroi basin went on strike. A rally took place on the Place de Gilly where a thousand people responded to the call. Most of the strikers were armed with dangerous objects and continued the rampages.

Glass factories that had been known for automating their production were destroyed by rioting. The Robert factories, the Brasseur glassworks, and two extraction shafts at Le Mambourg were shut down and ransacked.

In Charleroi-North, one group went to the Jonet glassworks, where everything was destroyed; finished or semi-finished glass products, the furnaces, the molten glass... everything was ransacked. The same fate was reserved for the other glass factories in the area. Unemployed glass workers destroyed many of the factory's machines and equipment which threatened their jobs.

The revolt showed no sign of abating. The Badoux glassworks in Jonet was completely razed to the ground by fire, followed by the crowd then attacking the castle of Mr and Mrs Baudoux, which was so large that it incited more anger in the crowd. Surging forwards into the premises, protestors stole the wines, champagnes, silk, ceremonial clothes and wardrobes. The losses were estimated at two million Belgian francs.

Workers burn Mr Baudoux's glass factory and personal castle at Jumet during the strike, as depicted by Le Monde Illustré. Credit: Creative Commons

The violence sweeping across Wallonia was unprecedented. The Binard brewery of the Mayor of Châtelineau, the glassworks of l'Étoile, the blast furnaces of Monceau and Ruau all suffered the same fate.

At around 21:00 that evening, strikers marched towards the Roux glassworks to also set it on fire. Here, the troops sent by the Minister of War, under orders of Lieutenant-General Alfred Vander Smissen, arrived on the scene and opened fire on the crowd. Five people were killed and a dozen wounded.

Following days of violence, on 27 March Charleroi was placed under siege by the Belgian Army. The government recalled 22,000 reservists from the army and charged Vander Smissen with restoring order.

Shortly after the Lieutenant-General and his troops arrived in Charleroi, he gave the order to stop the riots at all costs. He authorised locals to organise bourgeois patrols, armed with shotguns and revolvers. Vander Smissen then gave the fatal order to shoot at the strikers without warning.

In Roux, a second mass shooting happened that day when strikers crossed a bourgeois patrol where another 12 workers were killed by the army. On 29 March 1886, Vander Smissen's violent response helped him to "triumph" over the rioters, effectively suppressing the 11-day revolt in blood.

The aftermath

Over the course of the strike, over 20 demonstrators were killed, including 12 in the (second) Roux shooting alone. Hundreds were injured. Just like the Paris Commune of 1871, the popular revolt was violently put down by authorities.

In the aftermath, 27 alleged revolt leaders were tried before the court of assizes in Mons in May 1889. Highly publicised in the media, the trial collapsed when it emerged that the Belgian intelligence services (Sûreté Publique) had infiltrated the radical group, acting as agents provocateurs.

So was it all worth it? While the revolt failed to achieve many of its tangible aims, a parliamentary Labour Commission (Enquête du Travail) was created in the aftermath of the general strike, which led to the first labour legislation in Belgian history.

This marked the first time a workers’ revolt gained concessions from the national government.

Following the general strike, Belgium also saw the biggest expansion of trade union membership in the country, as well as the emergence of the first parliamentary socialist party, which aimed to redirect workers' demands away from violence and towards the cause of electoral reform.

"Today in History" is a new historical series brought to you by The Brussels Times, aiming to take you on a trip down memory lane for newcomers and Belgians alike, written and compiled by Ugo Realfonzo & Maïthé Chini.