Even by the standards of the 19th century’s colonial scramble Belgium’s treatment of Congo was particularly rapacious. Appropriated as the Congo Free State in 1885, the colony was not a state-controlled territory, but rather King Leopold II’s private property.

Leopold’s stated goal was to bring civilisation to the people of Congo, yet his rule became infamous for its brutality.

Estimates vary, but about half the Congo population died from punishment and malnutrition during the imperial period, which lasted until it was handed over to the state in 1908. It remained a colony until it won its independence in 1960, and became the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Belgium justified its control over Congo by claiming that the African people benefitted from its intervention, and grand architecture was a key tool of this propaganda effort.

The most effective platform for this was international exhibitions, showcasing the wealth of Congolese goods and artefacts Belgians had taken and displayed. It even led to the development of a special ‘Congo style’ linked to Art Nouveau to link the cultures of the colony and the coloniser. The immense Colonial Palace at the Brussels International Exposition of 1897 aimed to win over investors and convince the Belgian people to support Leopold’s imperial project.

‘Style Congo. Heritage & Heresy’ a new exhibition at CIVA, the Brussels region’s modern architecture museum, details this effort to weave their art forms together. Running until September 3, it reveals how Congo was a source of fascination for artists and architects of the time with its ‘exotic’ materials and forms. By the end of the 19th century, the term ‘Style Congo’ was used to describe what is now known as Art Nouveau– although architects and artists were reluctant to draw a link to the colonial aspect of this architectural movement.

Paul Hankar's ethnographic room in the Colonial Palace in the 1897 Brussels International Exhibition in Tervuren

The CIVA exhibition explores the politics of cultural representation and appropriation through contemporary art works and historical material from its collections. Its focus is how Congo was represented in international and colonial exhibitions from the 1885 ‘Exposition Universelle’ of Antwerp to the Expo 1958 in Brussels, the last in which Congo was presented as a colony, as it became an independent republic two years later.

“Architectural production cannot be reduced to a mere formal or aesthetic practice,” says exhibition art director and co-curator Nikolaus Hirsch. “It is deeply entangled in political, economic and social debates.”

The exhibition includes works by renowned architects from Ernest Acker to Henry Van de Velde, not to mention Belgian garden designer René Pechère, showing how they exploited ideas from Congo for their work.

CIVA’s collection of drawings, paintings, plans, photographs and postcards from the period between the 1885 and 1958 international exhibitions, highlights Belgium’s mistreatment and patronising attitude towards the Congolese people. For example, in one 1885 photograph, a group of Congolese sit outside their typical ‘colonial’ house with extensive use of wood and stairs going up to the veranda, but a white Belgian man is symbolically in the centre of the image.

Human zoos

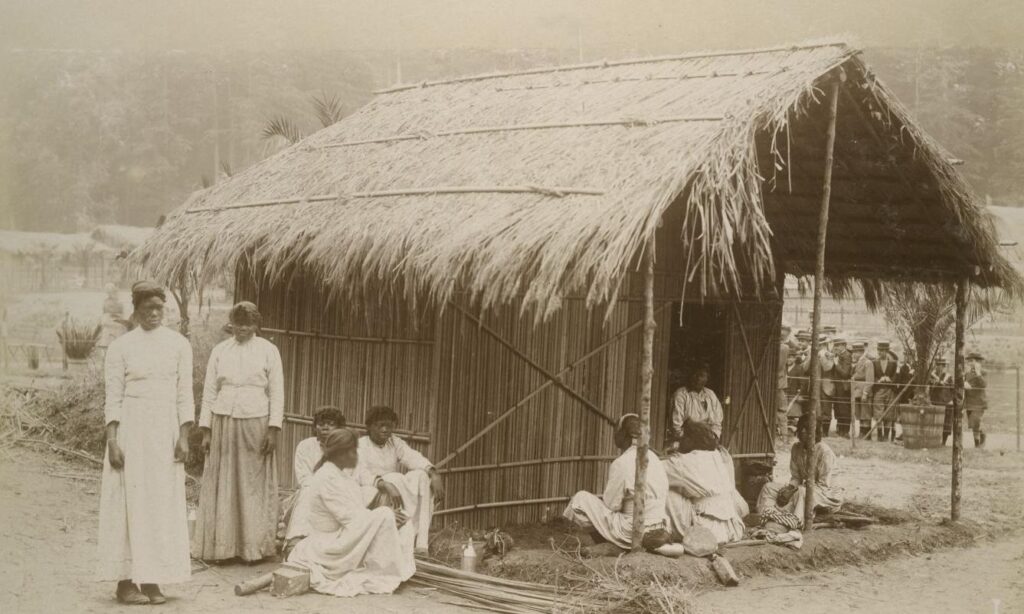

Other material includes photos of the Congolese people in traditional dress, in their ‘colonial villages’ at the international exhibition, or the notorious ‘human zoos’, also known as ‘jardins d’acclimatations’. Some 267 Congolese people were brought to live in the 1897 exhibition, and seven did not survive their stay. In parallel, the Congo Pavilions were seen as memorials and as a kind of thank you to Leopold II for his work in ‘civilising’ and ‘liberating’ the Congolese people from slavery.

'Congolese village' at the 1897 Brussels International Exhibition in Tervuren

Major figures produced the imagery to represent the Congo in these colonial exhibitions, including Auderghem painter Alfred Bastien and 1930s Modernist architect Victor Bourgeois, while Art Nouveau architect Paul Hankar also helped design the pavilions for the 1897 exhibition in Tervuren.

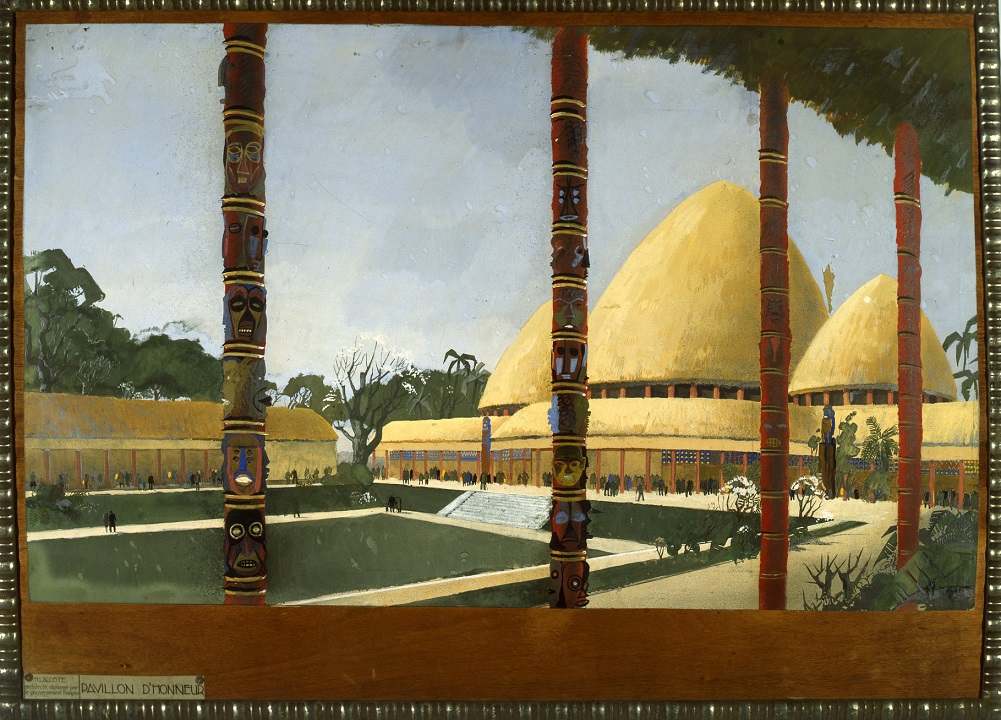

Architect Henry Lacoste’s striking 1939 poster of the Congo Pavilion at the Liege international exhibition, mixing African masks and 1930s architecture, is a highlight of the show. Another notable example is French architect Georges Hobé’s Art Nouveau/Style Congo structure using African Bilinga wood to evoke a Congolese forest in the 1897 exhibition’s main hall.

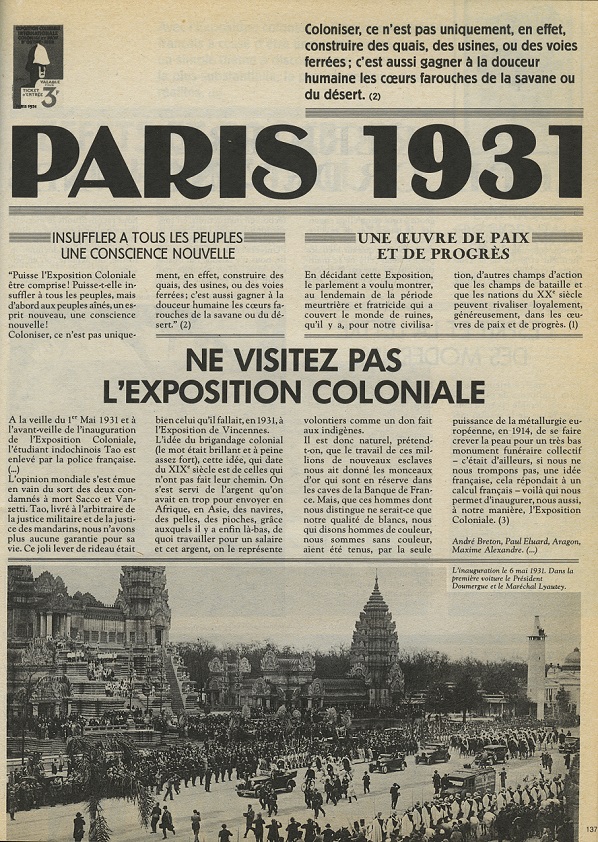

However, even in the 1930s, the expansion of the Belgian Congo and its ‘civilising mission’ was not to everyone’s taste, with some pointing to the near-slavery and economic exploitation of the colonial operation. Traditional historical narratives are questioned, notably by a 1931 newspaper article headlined ‘Ne visitez pas l’exposition coloniale’ (‘Don’t visit the colonial exhibition’) and signed by literary figures like French poets André Breton and Paul Eluard.

1931 appeal to boycott the Colonial Exhibition in Paris

And yet the idea that Africa was ‘explored and civilised’ was highlighted in posters, in newspapers and newsreels. A short film at the CIVA exhibition shows Edmond Leplae, the Director of the Agriculture Department at the Belgian Ministry of the Colonies, who tries to explain how the coloniser’s house was an instrument for a ‘mise en valeur’, or enrichment of Congo.

Henry Lacoste's image of the Belgian pavillions at the 1931 Paris International Exhibition

Meanwhile, the Belgian authorities enthusiastically promoted the idea that Congo was a lush green paradise with vast nature reserves that would benefit from scientific research, to justify its presence on the territory. The exhibition emphasises this environmental aspect, explored for example in Lacoste’s panorama of the climate, finally never realised, meant for one exhibition’s main hall.

But history has moved on and Congo is no longer a colony. More than six decades after independence, Belgium is finally asking itself tough questions about its role as a coloniser, and its legacy – including the statues and monuments of Leopold II that still adorn public spaces.

The CIVA exhibition includes modern-day interpretations of the Style Congo-Art Nouveau link: photographer Chrystel Mukeba captures Belgians with Congolese backgrounds in some of Brussels’ most iconic Art Nouveau buildings, such as the Horta-designed, UNESCO World Heritage-listed Hôtel Van Eetvelde on Avenue Palmerston (particularly piquant as the Hôtel was built for Edmond Van Eetvelde, the first General Administrator of the Congo Free State).

Hirsch, the exhibition’s curator, says Belgium cannot ignore the mistakes and atrocities of Belgium’s colonial past, but it can recontextualise them. “History is not finished, it is dynamic,” he says.

Style Congo. Heritage & Heresy. CIVA, Rue de l’Hermitage 55, 1050 Brussels. Open Tuesday to Sunday 10.00 to 18.00. There are also special activities planned for Congo Independence Day, Sunday June 30.