Lover gone? Business on the ropes? Alone in a cruel, chaotic universe? Worry not – help is at hand. Or at least, so goes the offer of countless psychics, clairvoyants, witch doctors, holy men and mystics – printed on little papers and distributed into letterboxes around Brussels.

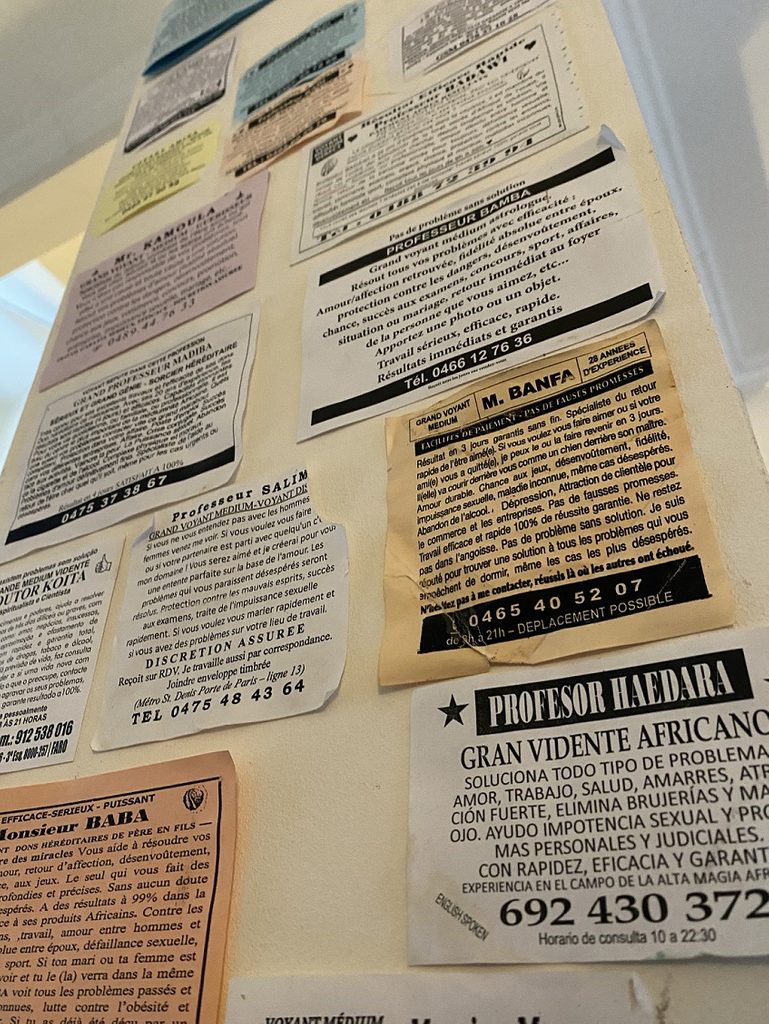

The flyers come in all colours of a pastel rainbow, with a cocktail of fonts, promises, and names. The most common honorific is Professor, followed by the humbler Mr. Then there is the job title, which includes SEO-friendly terms like “Grand Voyant Medium Astrologue” and “Grand Marabout Medium Africain”.

Potential challenges include bringing back a loved one, undoing a bewitchment and “making the person you love crazy for you”, as well as dealing with depression, impotence, alcoholism, family problems and much more. A common motto: “No problem without a solution”. Other claims include “Results immediate and guaranteed” and “Ease of payment” (in case there were doubts).

I have questions. The first concerns a word that sticks out to me: marabout. From Arabic (murabit means “one who is garrisoned”), it originally denoted Muslim clerics in the army. It came to refer to schools of mystics following Sufi teachings in sub-Saharan Africa, and over centuries pre-Islamic rituals mixed with those of the faith, to create a syncretic fusion.

The term can still refer to a wandering mystic living from alms. But now, especially in France and Belgium, many fortune tellers call themselves marabouts.

But I have many other queries. Why do the papers all look the same – despite different phone numbers? Is some central office directing a network? What kind of clientele calls them? What practices are used? Are they charlatans bilking the needy, or are they noble souls who believe in their work and results?

I set off to find out. My initial strategy is to pretend to have an issue and record the experience. But having read shady stories, I’m worried. The most famous involves French footballer Paul Pogba. Last year his older brother posted “revelations” that Pogba, then playing for Manchester United, had asked his marabout to curse Kylian Mbappé ahead of a game against Paris Saint-Germain in March 2019 (if so, it worked – United won 3-0). Pogba has denied this, as has his marabout – though even the fact he had a marabout raised suspicions.

Early this year, a marabout was found guilty in Isère in southeastern France of extorting a client who was attempting to win his neighbour’s heart. The client had already paid several thousand euro for various procedures when he was persuaded to steal his neighbour’s panties and lie naked with them on a bed. He was duly filmed and blackmailed by the sorcerer to the tune of €26,000.

All things considered, I decide to give an honest explanation upfront. I collect as many flyers as possible and scour online for more. Websites range from tracts of search-engine-friendly terms under a fuzzy photo, to shiny, fancy ones with testimonials, photos of candles, etc.

The flyers come in all colours of a pastel rainbow, with a cocktail of fonts, promises, and names.

I start to phone around. A good percentage of numbers don’t work. Of those who answer, varying possibilities ensue. We either don’t understand each other. Their accent, my accent – the whole concept gets lost; even when my French partner calls on my behalf. Otherwise, they do understand – and say no. Or ask for exorbitant sums. Or are impossible to pin down: they turn out to be in France. Or Luxembourg. Or Switzerland. One says he’s interested but makes me play phone tennis for days before disappearing into the ether.

As the paper trail goes cold, I ask friends, contacts and even speak to professors of ethnoanthropology. I hit the African quarter of Brussels, Matongé, and ask around. Most people look at me askew. Several tell me such practices are “haram” – forbidden in Islam. I’m directed to a Senegalese shop – but they can’t help me. I ask a customer who responds passionately, “I’ll tell you something – Jesus Christ died for your sins.” Dejected, I head home.

Behind the mask

Just as hope seems to be fading, divine intervention strikes. It is at Place Jeu de Balles flea market, where truly anything can be found. I’m examining some wooden Gabonese masks, from a kind and knowledgeable seller. My partner realises she has no cash, and I dash home. When I return, she’s chatting with the vendor and has discovered that he’s a marabout! “But I don’t do it for money,” he clarifies. “Just to help people.”

His name is Elhadja and he’s a Cameroonian with an encyclopaedic knowledge of African masks. One miserably dark and rainy weeknight we visit the tiny Schaerbeek flat he shares with his brother. He comes down all smiles in a traditional gown, and space is cleared for us to sit amid piles of merchandise and belongings. And he opens up.

Elhadja followed his late father, who began bringing masks, statues and antique objects from Cameroon into Belgium in the 1960s. From an early age, he was immersed in the world of these wares, travelling throughout West Africa and picking up artefacts. “Every village has its own specificity,” he explains. But there was something else that fascinated him: maraboutage. His uncle practised it, not as a profession, but to help others, and the 15-year-old begged to be taught. Rebuffed at first, his uncle then relented, because “I was curious. And I was courageous.”

Elhadja at the Place Jeu de Balles flea market

For maraboutage, he explains, “you have to be sincere. A marabout has a mystic knowledge that comes from God. But he has to learn it.” What about the many psychics out there? “There are real marabouts and fake marabouts,” Elhadja says. He says the fakes will perform a trick to make you believe, and then use this power to exploit you. You might go with a stomach ache, for example, and he will produce a mouse, saying he’s extracted it from inside you. Whereas the real marabout comes with “pure intentions” and communicates only with God.

Most true marabouts use Islamic scriptures, while some might integrate other texts like the Old Testament or ancestral secrets. Elhadja uses only the Qur’an. His approach is ruqyah – a healing method based on Islamic teachings, involving repeated recitation of certain verses. He’s used this to help many people with illnesses and other issues, such as bewitchment.

What does it feel like to be bewitched? After a pause, he replies. “Like a blockage. Like my life is not as normal. I feel a certain negativity in my life.” He speaks slowly and rhythmically. “God says certain people are born with negativity. They can look at you and the positivity in your life, and transform it for the worse.”

In conversation punctuated with quotations of scripture, he tells us of the jinn, invisible spirits in the Islamic faith, rooted in older cultures. Created by God to exist on another plane of existence below humans, he says they can inhabit toilets and dustbins. False marabouts, he says, call upon the jinn, which is forbidden. They use red and yellow candles to help attract them, for example.

Elhadja’s process is different: recital of scriptural verses, using rosary beads, perfumes, olive and Nigella sativa oils – all to banish evil and purify the spirit. Back at home, live animal sacrifice might be called for, but since it’s illegal in Belgium, it’s replaced by giving to the poor. And then, it’s about connecting with God based on a clear intention, during one or two days of a sustained trance. Not a million miles from a meditation retreat.

But can it achieve such things as success in love? “It’s possible, but only if the man or woman are sincere,” he says. I picture the naked man in Isère holding his neighbour’s panties. Probably not that sincere, no. “Maraboutage exists,” says Elhadja. “But as the Qur’an says, you must suspect your human brother. God knows we’re bad.”

We discuss his life and Elhadja shows us pictures of his daughter, sick, awaiting an operation in Cameroon. He cannot travel for visa reasons and strives to send funds home to his family. And yet, he’d never seek money through maraboutage.

The last flyer

I had given up on getting in touch with the letterbox psychics when I receive one more flyer – from someone who identifies himself as Professeur Hamza. Something about the paper seems different. I’ve seen so many of them that I’ve become a connoisseur. It’s large and crisp, with a humbler claim: “Channelling the gifts of his ancestors”. I call, and he answers. I explain and he accepts. Stars are aligned.

I head again to Schaerbeek on a frozen morning and descend into a basement. My eyes adjust. It’s lit with candles; filled with a pleasant aroma of spiced incense. Hamza invites me to a table. On it are papers lined with elaborate Islamic script. Shells, horns, and furs cover the surfaces, and ornate clothing hangs on the wall. Hamza is dressed in a traditional robe, his hat strung with dangling beads. He drapes a white cloak over my shoulders and we talk.

In his mid-30s, tall and austere, Hamza comes from the Senegal-Mali frontier. A marabout is there to help when someone does something bad to you, he explains. Or for certain ailments that cannot be cured in a hospital. Or when people need good advice to make good decisions. To deal with trauma or couple trouble. “Not many people around here believe in bad spells,” he says. “But they exist, and we can block them.” Like Elhadja, Hamza is quick to specify that he’s on the bright side. “I don’t do any bad spells, cause harm to people. I don’t help people who ask for that.”

What’s the approach? Does he use ruqyah, like Elhadja? While that’s good for calming you down, Hamza says it doesn’t deal with a problem’s root. Marabouts might use various methods – working with sand, shells, cards, numerology – but they are all to see clearly and guide the right decisions. Some conditions require special approaches. He might, for example, go out with the client to a forest. While marabouts from Benin might use voodoo arts, Hamza says, he only uses the Qur’an, along with plant medicine – natural extracts brought from Africa. He shows me a sachet filled with white powder. “For sexual potency,” he says.

Like Elhadja, Hamza learned from his forebears. His grandparents and parents were marabouts. As an infant, he was present in the sessions. As a child, he foraged for plants with his father, though he was sometimes scared of the snakes. He moved to Dakar, Senegal, to spread the family business, while his father stayed home. Then he made the long journey to Europe, stopping in Spain, then France, gaining citizenship, before reaching Belgium.

It’s satisfying work and Hamza sees the benefits. He’s received calls from people on the brink of suicide, talking them down over the phone. But he doesn’t sleep much. Sometimes he’ll call a patient in the middle of the night, asking them to sit up while he prays for them. What does he do to restore himself? He shows me a long wooden slab, a stylus, an inkpot – for etching holy verses.

Who visits? All kinds do: young, old, women, men, Belgians and foreigners. People in Europe are sceptical, but they come anyway. They see the benefit and come back and recommend him to family and friends. And so, it spreads. Hamza chides me for asking questions. “You want to explain it, but you can’t explain it,” he says. “You have to experience it.” Showing me out politely, he urges me to call him if I need his services.

I consider the place of the marabout in Brussels. The therapies I’ve experienced through the years are those available to me as a person from a certain background. Despite my scepticism of the flyers’ promises, the problems listed on them are a map of the human condition. And judging by the number of them, there must be plenty of people who don’t know where else to turn. It might seem to many like a last resort, but both the problems raised by the marabouts and their responses are very familiar to those of us used to more conventional means. I recall the words of Elhadja, “If you choose the good path. You’ll be shown the good path.”