Belgian expert Ludo de Witte has written two books about Belgium’s colonial past. Ahead of a new book by journalist Stuart A. Reid (The Lumumba Plot: The Secrete History of the CIA and a Cold War Assassination), he says that he still sticks to his conclusion that Belgium was primarily responsible for Lumumba’s death.

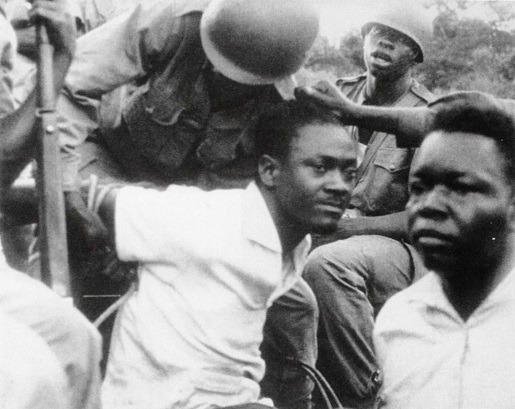

When the Belgian Congo gained independence in 1960, 35 years-old Patrice Lumumba became the country’s first prime minister, only to be assassinated shortly afterwards in a plot with Belgian involvement, while Congo descended into chaos despite the presence of United Nations peacekeeping forces.

In a book published in 1999 by Belgian sociologist and historian Ludo De Witte, the author concluded that Belgium was primarily responsible for Lumumba’s death. The book resulted in the establishment of a parliamentary commission of inquiry to determine the exact circumstances of the assassination of Lumumba and the possible involvement of Belgian politicians.

“Belgium’s responsibility is beyond any doubt,” he told The Brussels Times in an interview about Reid’s book, due to be published in October. De Witte is an expert on Belgium’s colonial past and worked 6 years on his book on Congo.

Tragic series of events

“The problem with all reports and books, including my own book, is that they don’t look into the whole picture and don’t include all actors”, says de Witte, referring to Belgium, the US, the United Nations, the Soviet Union, and local Congolese actors. But he still sticks to his main conclusion and lists a number of compromising facts in the tragic series of events that led to Lumumba’s’ death.

When chaos erupted in Congo, Joseph-Désiré Mobutu Sese Seko, the army colonel who later would become the despotic ruler of Congo, stepped in and took power with his troops. He placed Lumumba under house arrest in his residence, guarded by Congelese and UN troops. Lumumba managed to flee by hiding in a car, but was captured on 1 December 1960 and imprisoned again.

On 17 January 1961, Lumumba was brought by Mobutu’s soldiers to the breakaway region Katanga, which was ruled by Moïse Tshombe, urged to do so by the Belgian Minister of African Affairs. Allegedly it was because it was feared that Lumumba could be freed by his supporters. In practice it was a death sentence.

Belgian secret agents organized his transfer from prison. He was flown on a Belgian Sabena plane to “custody” in Katanga. Belgian officers reported how he was treated there and even participated in the torture of him. They were ordered to shoot him if there was any attempt to free him. They organized the firing squad.

Within five hours after the arrival of Lumumba and two of his collaborators, they were brought to an open spot in the savanna and executed.

This does not absolve the US and the UN from their responsibility, De Witte says. They also played an important role in undermining Lumumba. The US planned already in mid-August 1960 to assassinate him. But the only plan which actually was carried out and led to his death was the Belgian plan.

In August 1960, finding no help from the West and the United Nations to end the Katangese secession, which was organised by Belgian officials and military, Lumumba asked the Soviet Union for support. The Soviet Union sent trucks and airplanes. In the atmosphere of the Cold War in the 60s, this was enough to regard Lumumba as a dangerous Communist.

Belgium’s colonial interests

But De Witte does not agree with the common perception that the assassination of Lumumba should be understood in the context of the Cold War. “The role of the Soviet Union has been blown up beyond any proportion,” he says. “Four of the five resolutions in the UN Security Council were accepted by the Soviet Union. It abstained on voting on the fifth resolution which was taken after the assassination.”

All odds seemed against Lumumba. “He was not naïve but he miscalculated the support he could get from African-Asian non-aligned countries,” De Witte says.

“I was happy to have finished the book but the work didn’t finish since then,” he added. In 2021, he published another book on Belgium’s colonial past, this time on Burundi. He found a similar colonial pattern in Congo and Burundi with Belgium trying to preserve its interests. In both countries, the elected prime ministers were murdered in connection with independence.

Patrice Lumumba was murdered shortly after Congo had become independent. Lous Rwagasore, a member of a royal family in Burundi, who had been elected to prime minister with an overwhelming majority, was murdered on 13 October 1961 with the consent of the Belgian governor. Burundi would gain independence the following year.

King Baudouin played a disastrous role in both countries, according to De Witte. Brought up in conservative Catholic milieu and under the influence of his father Leopold III, who had been forced to abdicate from the throne, the King detested both prime ministers. But in Burundi, the perpetrators were quickly caught, brought to justice and sentenced to death or long prison sentences.

UN’s failed responsibility

As regards UN’s role, De Witte replied that it is difficult to fully explain it. “The Congo crisis and the deployment of UN peace keeping troops (the “Blue Helmets”) was United Nations’ first real test and it failed miserably.”

The legitimate Congolese government pleaded for help from the United Nations, headed by Swedish Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld. Following a UN Security Council resolution, UN peacekeeping troops under the command of another Swede, Major General Carl von Horn, were sent to Congo.

De Witte blames the Swedish general for being directly responsible for the capture of Lumumba by soldiers answering to Mobutu. Lumumba had sought refuge at the encampment of Ghanaian UN troops. They were commanded by British officers but 100 % pro-Lumumba. The troops were told by von Horn that they under no circumstances were allowed to take Lumumba into protective custody.

When Hammarskjold was asked about it at the UN Security Council he lied blatantly, according to De Witte. “He wanted to destroy Lumumba politically and didn’t realize that handing him over to his enemies meant a certain death sentence.” Hammarskjöld was surrounded by 4 aides, three of which were former US secret service agents.

Hammarskjöld died in a September 1961 in a plane crash on his way to talks with Tshombe. He was posthumously awarded the Nobel Peace Price and is considered a hero in Sweden. “I don’t think that Hammarskjöld changed his opinion about Lumumba even after he was murdered,” De Witte says.

No justice served

The official Belgian report from 2002 urged the readers to regard what happened in Congo in light of the Cold War in the 60s, “with different standards, ethics and norms.” But this is a ridiculous excuse, De Witte says.

“Assassinations and war crimes were forbidden and criminalized already then. The report did ascribe moral responsibility to the Belgian government but there were no legal consequences. In fact, the report did not adhere to the Parliament’s directive to assess the personal responsibility of those involved in the plot.”

“The conclusions in the report as regards Lumumba’s family were disgraceful,” he continues. Instead of recommending paying compensation to the family, given Belgium’s responsibility, the government proposed to establish a fund in Lumumba’s memory for support to the democratic development of Congo. The family would manage the fund. But the fund was never established.

In 2011, the family turned to the courts and sued the Belgian government for not honouring the decision. They also wanted to bring the suspected perpetrators to justice and named 12 persons. The case was admitted because the assassination of Lumumba was considered a war crime according to Belgian penal law. There is no prescription of such crimes when Belgians are involved.

A judge was appointed and he is still working on the case. By now only one of the suspects is still alive. Asked in 2020 about the slow pace, the federal prosecutor referred to the lack of staff. The inevitable conclusion is that there is no interest in finalizing the investigation and bringing the case to a closure.

The aftermath

If there is no trial, how can there be accountability? De Witte mentions two alternatives. The case could be brought to an international court, for example the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the Hague which tries individuals charged with war crimes. Another option could be a citizen-based public tribunal to raise awareness about the assassination and contribute to some form of accountability.

Meanwhile, some change is happening, albeit slowly. In 2018, the Square Patrice Lumumba was inaugurated in Brussels, on the corner of the Porte de Namur, next to the Matongé district, the heart of the city’s Congolese diaspora.

In the summer of 2020, the death of George Floyd in the US and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests spread to Belgium and led to a clamour of calls for the country to remove its colonial-era statues and monuments – and do more to recognise its culpability towards Lumumba.

And then, there was the gold-capped tooth. It was all that was left of the remains of Lumumba that had been taken and kept for years as a trophy by a Belgian police officer who had not been involved in the execution of Lumumba but been ordered to dispose of his body after he had been killed.

The tooth was handed over to Lumumba’s family at a ceremony in the Egmont Palace in Brussels in June 2022. Prime Minister Alexander de Croo said that Belgium recognised its “moral responsibility” for Lumumba’s killing. “This is a painful and disagreeable truth, but must be spoken. A man was murdered for his political convictions, his words, his ideals.”

The plane crash where Dag Hammarskjöld and fifteen others on board died in 1961, is still unsolved. The first investigations concluded that the most likely cause of the crash was pilot error. The UN investigation, which was renewed in 2015, mentioned the probable existence of communication interceptions which could have enabled an attack against Hammarskjöld's plane.

The crash is still a national trauma in Sweden. The UN investigation, which was conducted by Tanzanian lawyer Mohamed Chande Othman, was again extended in December 2022 at the request of Sweden.

A member of the Swedish parliament, Christian-Democrat Gudrun Brunegård, recently filed a proposal to establish a “truth commission” to examine Sweden’s political considerations in 1961-62 and analyze documents that still are classified as secret. However, her proposal was rejected by the foreign affairs committee of the Swedish parliament.

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times