An extra day has been added to the end of February this year as 2024 is a leap year. But why is there a 29 February? How many people celebrate their birthdays today, and how? And is it possible to get rid of leap years?

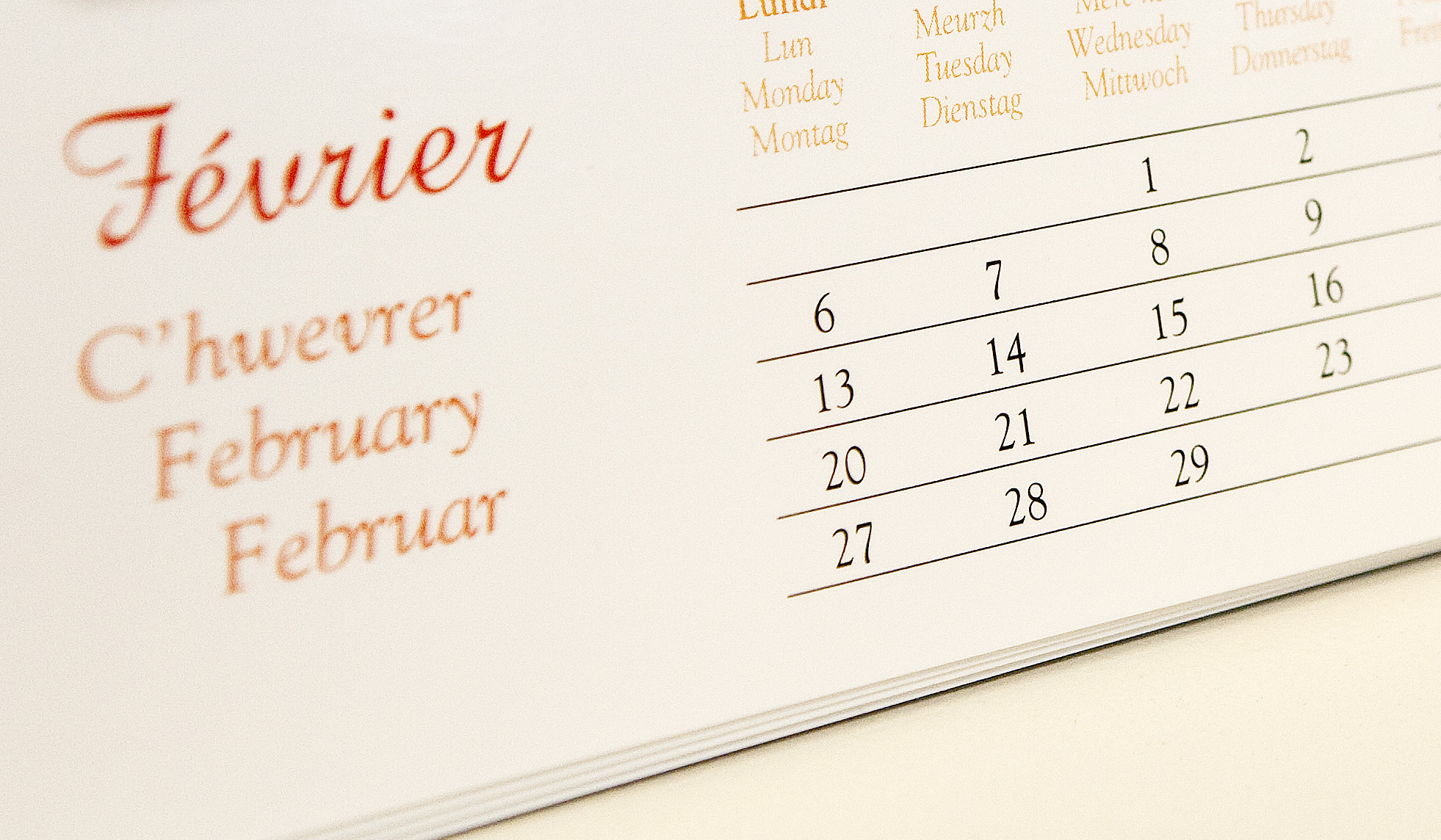

Once every four years, a leap year occurs, in which one extra day (29 February, referred to as "leap day") is added to the calendar. The last time this happened was in 2020.

A useful way to recognise leap years is when the number is divisible by four. Centurial years are leap years if they are exactly divisible by 400: the years 1700, 1800, and 1900 were not leap years, but the years 1600 and 2000 were.

Why do leap years exist?

Around 190 BC, the Greek astronomer Hipparchus determined that a complete rotation of the earth around the sun – a year – lasts 365.242347 days or about 365 and a quarter days. Undercounting a quarter of a day four years in a row leaves people running a full day behind the lunar calendar. This is where the problems began.

If the calendar is inflexible and the fixed system of 365 days a year (in the Egyptian calendar introduced by Julius Caesar) is implemented, these seasons soon get out of sync. Eventually, the new year would start in autumn, or even in full summer.

The concept of a year is the key indicator of time for nature which relies more on the seasons. Plants, animals, rivers and other natural elements live according to this clear annual pattern. As people relied (and still do) on seasons – for sowing, harvesting, building, working, and living, but also for religious holidays – they too had to adopt the concept of years.

In the 16th century, the seasons shifted and this created ambiguity about Easter, the most important feast of the church year. This called for an intervention in 1582 when Pope Gregory XIII skipped ten days. Thursday 4 October 1582 was followed by Friday 15 October 1582, resulting in the calendar again being in step with the seasons and with the Easter date.

Because of this intervention, a year in the Gregorian calendar lasts 365.2425 days.

Missing birthdays

Few feel the impact of an extra day every four years – apart from those born on 29 February. In Belgium, no fewer than 7,220 people will finally get to celebrate their real birthday again on 29 February 2024.

In Flanders, some 4,114 people will be putting on their party hats today, while in Wallonia and Brussels, 2,381 and 725 people will be blowing out their candles, respectively, figures from Statbel, the Belgian statistics office, showed.

Credit: Belga / Elisabeth Callens

There is even a Schrikkeltweelingenclub ("leapfrog twins club"), consisting of about 30 twins from the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany, who meet every year to celebrate their birthdays.

People born on this day usually have to celebrate their special day slightly differently than those born on any other day, either on 28 February or 1 March. Legally, a leap year child only turns one year older on 1 March in Belgium.

Traditions and superstitions

In some countries, there are unique traditions linked to leap years. According to old British traditions, for example, this date is the only time the woman in a relationship can break with convention and propose to her partner. This was seen as a concession for women who had to wait too long to be asked for their hand in marriage.

In France, 29 February is the only day when a newspaper called La bougie du sapeur (The Sapper's Candle), which was founded in 1980, published a paper. This year it will publish its 12th edition. The paper can also be bought in Belgium.

Related News

- Feasts, flags and funny hats: How Belgium celebrates its birthdays

- What are the most popular names in Belgium this year?

In Spain, the leap year or leap day itself is considered bad luck. This is unfortunate for the country's Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez, who was born on this day in 1972. The country even has proverbs summing up the country's feelings about the phenomenon, such as año bisiesto, año siniestro ("leap year, ominous year").

In Greece, Ukraine, and Italy too, superstitions suggest that leap years bring bad luck or are associated with ill omens. Couples are often cautious about planning weddings on leap years.