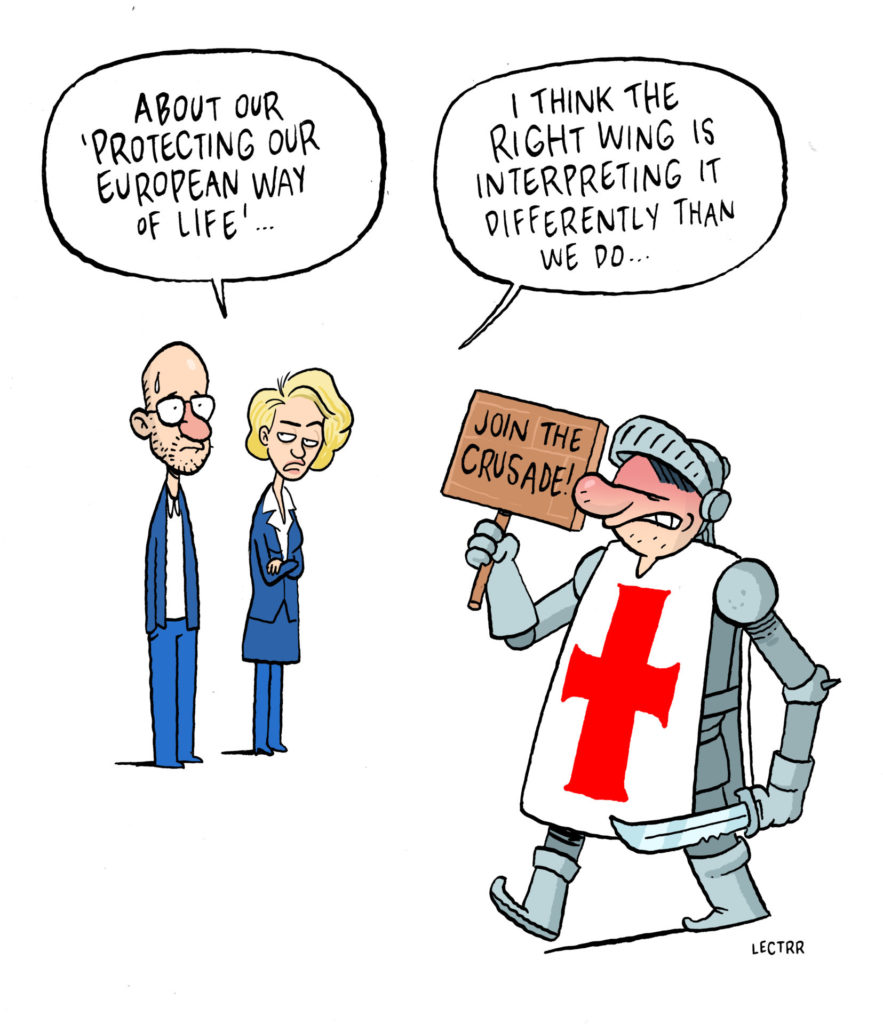

In September 2019, the newly appointed president of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen made public the list of portfolios to be distributed among the members of her future Commission. One of these portfolios, intended for the former chief spokesman for the European Commission, Margaritis Schinas, covered a wide range of subjects, from migration and border security to integration and culture. The title she proposed to give to it was “Protection of our European way of life”. At this time, we don’t know whether this title will be confirmed. What we do know is that it triggered an intense controversy. Rightly so?

Understandably so. To start with, the use of the singular is problematic. Do we Europeans really have one single way of life, from Cyprus to Northern Sweden and from Ireland to Bulgaria? Do even Belgian citizens of Belgian descent all have the same way of life.

Moreover, in countless documents, the European Union celebrates its linguistic and cultural diversity. This implies not only that we do not have a single, unified way of life, but also that we do not want to have one.

Had the plural been used, would the title of the migration portfolio then be OK? Is the protection of our diverse ways of life a legitimate objective?

What does “protection” mean? If it is understood as preservation against alteration, the threat one should be most concerned about has nothing to do with migration. The main threat to the preservation of our ways of life, in Europe and elsewhere, is not the invasion of foreigners but the invasion of computers. The title, therefore, would be more appropriate for the commissioner in charge of the digital economy than for the one in charge of migration.

The omnipresence of computers, the internet and social media makes ways of life differ more deeply between generations than between nations. Technology-driven changes in our daily lives have happened on a massive scale and at an accelerating pace since the beginning of the industrial revolution. Many more can be expected. Indeed, the impact of our technologies on our environment and our climate require us to urgently modify many of our European ways of producing and consuming, of moving and keeping warm. These do not need protecting at all.

Isn’t there nonetheless something that could be regarded as a shared inheritance by all Europeans, despite variations in space and time, which deserves to be protected?

In the statement she published on 16 September in various European newspapers to justify the label she chose, Ursula von der Leyen wrote that what she called the “European way of life” was summed up in article 2 of the Treaty of the European Union. That article refers to a number of “values” on which the Union is said to be founded — human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law, human rights — and to a number of features that are said to “characterise” European societies — pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity, gender equality.

During his hearing at the European Parliament on 3 October, Margaritis Schinas adopted the same line of defence. This list is quite a messy hodgepodge of overlapping values and features, none of which is the exclusive preserve of European countries. However, these values and features are enshrined more or less explicitly and effectively in the European treaties and in the constitutions of the member states, and they inspire and justify a remarkable institutional framework that has emerged laboriously in Europe from centuries of thinking, debating and fighting.

It is to this institutional framework, not to the peculiarities of their DNA, that the residents of the European Union owe the privilege of enjoying an exceptional combination of freedom and peace, of prosperity and solidarity. This institutional framework deserves to be protected. Indeed, it is arguably our historical responsibility to secure the conditions for its survival and ability to flourish. And these conditions include — on the part of both “natives” and “immigrants” — a widespread endorsement of the underlying values and the widespread adoption of attitudes and practices animated by these values.

Isn’t this what Ursula von der Leyen meant?

To be fair, judging by her explanatory statement, this is quite probable. The problem, as revealed by some of the reactions, is that the expression “way of life” has connotations that go far beyond what is needed for our precious institutional framework to survive and thrive. Protecting our European way of life can be understood, for example, as requiring newcomers, if not immediately at least after some generations, either to secularize or to attend “our” churches, to drink beer or wine rather than mint tea, to eat pork rather than ritually slaughtered mutton.

In some circles, it is even understood as requiring “immigrant” women to exhibit just as much of their hair, limbs and breasts as 21st century “native” women are standardly doing. A wide variety of imported ways of life — of worshipping, eating or dressing — are perfectly compatible with our institutions. Unlike the learning of our local languages, the adoption by newcomers of our local ways of life in this sense is by no means necessary for “integration” or “social cohesion”.

Some people criticized the label, not so much because it suggests a dubious objective, but because the EU’s migration policy is being reduced to its pursuit.

I agree with them. Let us interpret - generously - the “protection of our European way of life” as the preservation of the conditions for the survival and flourishing of what is valuable in our institutions. Does immigration hinder the pursuit of this objective? It does not need to: immigrants are just as able as natives to endorse the values that underpin the institutions and to adopt the attitudes that enable these to function smoothly. But it certainly can if it happens at such a rate and in such a form that the necessary socialization process cannot keep up.

Given that the powerful pressure on our Southern borders is not likely to abate any time soon, this means that immigration and integration policies are among the policies that can contribute to the “protection of our European way of life” in the sense indicated. But it would be wrong to design them with nothing in mind but this defensive concern.

It is not just that well-integrated immigrants can enrich our societies both economically and culturally. They can and must also play a crucial win-win role as diasporas. Lasting and fruitful relations of trade, investment and technology transfer in a broad sense require mutual trust.

And this trust is most easily secured by go-betweens who are at the same time full members of the country in which they live and strongly connected with their country of origin. Making good use of our many diasporas, including a view to reducing migration pressures, is as important as protecting our way of life, even in the most sensible interpretation, as an objective to be pursued by the European Union in matters of migration and integration.