How do you build a city to withstand a global pandemic? Urban hubs are scrambling to redesign their roads and buildings to meet the needs of a new post-coronavirus era.

Londoners are demanding that their narrow, historic streets be made wider, and the use of e-scooters on public roads may be legalised to give commuters another alternative to the underground. In Liverpool new street furniture is being installed to allow people to socialise at a few metres distance, and in Milan more than 30km of cycle lanes are being created to encourage people to avoid public transport. Brussels, too, will have to find a cure to its winding, cobbled alleys – where collisions between walkers and shoppers are almost unavoidable – and its packed metro system.

Belgium’s capital has not been known historically for having a particularly thoughtful or diligent approach to urban planning. While New York gave us the grid system and Paris the elegance of Haussmannisation, Brusselisation has become a byword for just letting buildings sprout up where they may.

But the coronavirus pandemic has forced city planners to take a more considered approach. Belgium’s capital is set to gain a new 40km network of bike lanes, and the ancient centre has been given over to pedestrians and cyclists. Any cars that do enter are limited to 20km an hour and must give way to travellers on bike or foot. This will allow people to spread out further on the streets, and facilitate social distancing.

“Coronavirus has made cities and their inhabitants finally understand that we give way too much space to cars,” says Tom Sanders of perspective.brussels, the planning agency for Belgium’s capital. Social distancing, he adds, has also highlighted the need for more outdoor leisure areas and green space for people who don't have balconies or gardens. This has accelerated plans to create new public spaces, for example, in the city’s newly reclaimed canal docks.

A city in the remaking

The agency is also remapping the city’s layout so that every resident’s needs – whether for work, shopping or leisure – can be met within 10 minutes of their own doorstep. “People are rediscovering their local neighbourhoods, which is helping them to live more sustainably,” Sanders explains.

There is, however, a risk that these new requirements could cause people to withdraw from public activities, increasing loneliness and creating tribal divides between different parts of the city. “We cannot let this happen,” Sanders insists. The planners at perspective.brussels hope to challenge increased individualism through cultural and community spaces that are safe and open to all.

One type of building that may struggle to survive the pandemic is the traditional office. Tens of thousands of employees have switched to working from home, causing many businesses to question the need to pay for city centre space at all.

Brussels’ urban planners are currently looking at introducing many more houses and public amenities into the European quarter and North district to avoid buildings being left empty if employers get rid of their office space and move to remote working. “Offices will either be replaced or gain new uses as housing, hotels, schools, courtyards, greenhouses, sporting facilities…the possibilities are endless,” Sanders says.

Those workplaces that do remain open will need to be radically redesigned. Open-plan offices have been an almost fait accompli among Brussels employers in recent years, however Ryan Windsor, of architecture firm WindsorPatania, said their best days are long gone.

“Not only are they incompatible with social distancing, these spaces have also been shown to lead to lower productivity and employee satisfaction,” Windsor says. He predicts that coronavirus will power the transition to alternative office lay-outs. “We also have to prepare to have a lot more automation around us. There will be a move towards voice or sensor activated elevator buttons and door handles to avoid people having to touch surfaces.”

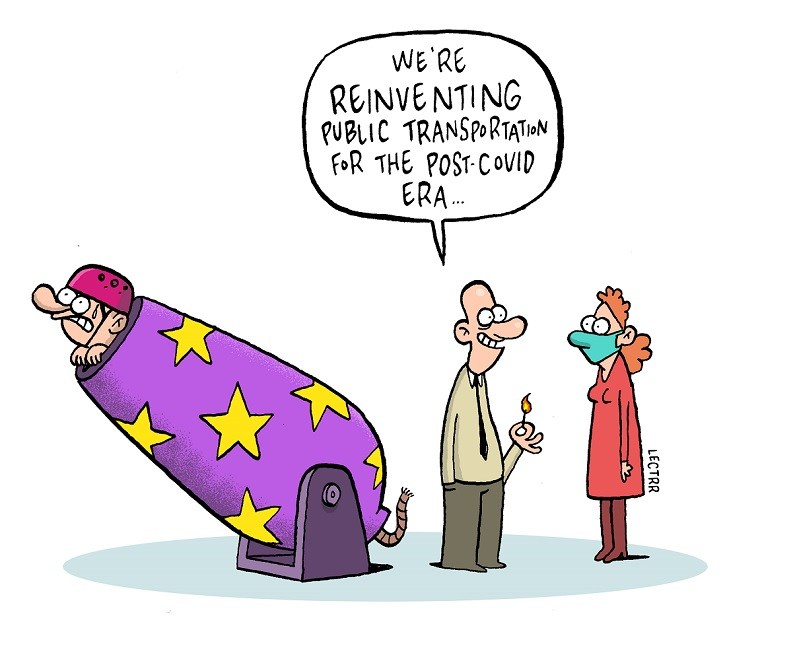

The pandemic may also spell the end of l’heure de pointe, or rush hour, dreaded by so many commuters. A large number of employers plan on staggering the start times of returning workers to ensure as little interaction as possible between people on public transport and in offices.

The result of all of these changes could have added health benefits. “Air pollution has been identified as a problem in Brussels for some time,” Sanders says. “Research has shown that pollution reduces the capability of our immune system to resist illnesses.” In an attempt to encourage people to avoid driving and cut down emissions going into the air, the city is considering introducing a toll on the use of cars by 2025.

Architecture vs pandemics

With people spending more time at home, much thought will have to go into the planning of new housing – or the redesigning of old – to ensure everyone has a comfortable and workable place to live. While Brussels already has relatively high standards of space requirements for residential building projects, one proposal is that all new homes will need to include some form of outside space. “Learning to live in a post-Covid era has given us many challenges, but challenging times often spur creativity, and it has also given cities huge opportunities,” Winsdor says.

Throughout history, architecture has never been immune to the effects of disease. After tuberculosis ripped through Europe and America in the 19th century – wiping out more than a quarter of New York's population between 1810 and 1815 – a new type of building, the sanatorium, began to crop up in almost all major cities across the two continents.

These health spas pioneered a new style of architecture. Light, airy, with white rooms, open terraces and clean lines: they were designed to prevent the spread of disease by giving patients as much access to sunlight and fresh air as possible. The popularity of their design eventually led to the birth of the Modernist movement in architecture.

Even earlier, the heavenly arches, spacious basilicas and lush gardens of the Renaissance found their source in the foul, dirted days of the bubonic plague. When around a third of Europeans lost their lives to the disease in the 1300s, local governments were forced into action, tearing down squalid living quarters, creating larger public spaces, and making use of experts skilled in everything from architecture to surveying. These cities, important centres of trade, did not struggle to find the funds to adapt. And neither will Brussels, home to the purse strings of the European Union, and a city where 2% of the population are millionaires.

Yet other places are not so fortunate. While citizens of Stockholm and Copenhagen are ready and willing to pay for their wide green spaces and slick cycle paths, those stuck in the slums of Delhi in India or Caracas, Venezuela have much less choice. The real key to whether a city will be able to withstand disease will depend on its ability to pay for its own defences.

By Marianna Hunt