Your train to Gare du Midi has probably ran right past the Wetsi Gallery, and you had no idea.

The windows of the art gallery sit along the railway on the first floor at Studio CityGate, a former industrial estate turned trendy workshop, just south of the railway on rue des Deux Gares in Anderlecht. The high, bright pink gate opens on a skatepark and a community garden. Inside, the Wetsi Gallery shares the space with Café Congo, an arty bar and events space, and with several artists’ studios.

Next to the comfy armchairs where Anne Wetsi Mpoma invites us to sit down, a small ‘decolonial library’ showcases books by Zadie Smith, Ben Okri and other black writers. This underground art space was pioneered by Café Congo in 2018 as a place to explore decolonialism, and welcome the cultures of people from African origins, or “Afro-descendants”.

This is what Wetsi Mpoma, a curator and art historian, is doing, too, with the Wetsi gallery. She decided to open her own space to display artworks from black artists, either African or Afro-descendants, because the lack of opportunity for them to showcase their work is staggering, she tells The Brussels Times.

The Wetsi Gallery opened in November 2019 with the goal of showing art that, “by its form or content, offers counter-narratives against the erasure of black artists in the world of modern and contemporary art.” Wetsi Mpoma isn’t afraid to tell it, bluntly: “This structurally racist system is depriving itself of a wealth of art. When black artists can’t exhibit their art, it’s a loss for them, for their communities, but also for Belgium. It makes no sense, and it’s sad.”

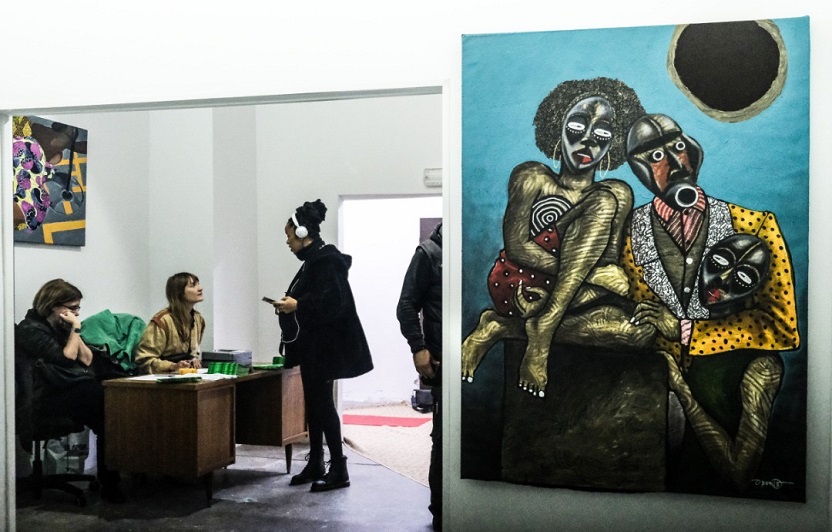

Walking into the Wetsi Gallery, a white cubicle in the corner of the vast open-space studio, the visitor is faced with a small selection of paintings and sculptures, all striking in their widely different styles. There is the series of three figurative portraits of chubby women by an Abidjan-based artist questioning body image in Africa; a painting reflecting on colonialism through the representation of the artist’s white father and black mother; an impressionist take on an upper-class Kinshasa salon; a painted snapshot of a basket full of beauty products bought in Brussels’ Matongé, and abstract shapes made of discarded material from landfill sites alluding to the arduous journey that migrants undertake.

Wetsi Mpoma gives the tour, explaining the professional path of each artist, as well as the artwork’s story. She is trying to show real images of Afro-descendents, she explains, away from “NGOs’ poverty in Africa stories” or idealised profiles of “Afropolitans”. “I can take risks, such as displaying art by artists who haven’t found their style yet. If people feel like they can’t make it into a gallery, their artworks might remain in a drawer. The first barrier is psychological: by being invisibilised, we invisibilise ourselves further.”

That’s true for all artists, she says, but especially for those who are black, and even more so for black women. She would know: born in Belgium to Congolese parents, Wetsi Mpoma has struggled with racism, in the art world and in Belgian society. “Every black person in Belgium has been discriminated against and has known racism,” she says.

“The mentality that developed during the time of colonisation is still around: this idea that colonisation had positive aspects, such as bringing ‘roads, schools and electricity,’ in short, civilisation, and that people in Africa would otherwise still be naked in the woods.” She recalls an email exchange with a collector of Congolese art, who implied he was helping her by dealing with her: “When, in fact, in providing him with the art, I was the one helping him!”

Colonial bias

Such colonial bias affects how black people are seen in art, too. After a recent trip to see the “Black Model” exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, Wetsi expressed regret in a blogpost that none of the artworks presented at the show were images of black bodies she would be happy to show her son: nude studies of black men, women and children, representations of maids caring for white children and enchained slaves.

“They were Blacks in subaltern positions in which [society] still wants to see them today,” she wrote, saying that in this light, the paintings became “abject and revolting”. Art, she added, should “allow populations who have suffered centuries of slave trade and colonial propaganda to be represented as human beings in their own right.”

It has been discussed for decades, but decolonial art became a hot topic with the re-opening of the newly designed Africa Museum in Tervuren in late 2018. The museum was criticised for its failure to do away with colonial imagery and racist representations, which it has partly preserved in its collections. Wetsi Mpoma consulted on the redesign as a member of the African diaspora, but the experience, she says, was “not good on different levels.”

Decolonial art has become a contentious topic with the redesign of Belgium’s Africa Museum in Tervuren.

“We were hired to give our opinion, but they did what they want. It felt a bit pointless.” Panels she wrote to put the current economic situation of modern-day African countries in perspective to the lootings of colonisation would be re-written, for instance. When she visits the museum, she says, she doesn’t read the explanatory panels any more: “It makes me angry.”

In February 2019, the UN called on Belgium to “recognise the true scope of the violence and injustice of its colonial past in order to tackle the root causes of present-day racism faced by people of African descent”, in a report that found that “racial discrimination is endemic in institutions in Belgium”.

“People of African descent face discrimination in the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights”, the report read. Among many other recommendations, it called for the Africa Museum to take colonial imagery off its walls. In response, Charles Michel, then Belgian Prime Minister, said that the UN report was “very strange” and that Belgium has “always tried to fight against any form of discrimination”.

“People don’t know, and don’t want to hear, that they are ideologically oriented, and that such an ideology comes straight from colonial times,” Wetsi Mpoma says. She still works with the Africa Museum on a freelance curating capacity and also gives decolonial art tours there, but is frustrated with the institution. For a long time, she says, she didn’t think of the Tervuren museum as art: “I was told it was history, not art. They don’t put the name of the artist or the person or community who made the artwork, but they put the name of the white guy who brought it here!”

In the art world, “white guys speaking about colonialism is seen as cool and trending”, Wetsi Mpoma says. Yet Black and African art remain considered a “subculture”, and artists of African descent won’t talk about their experience of racism in their art, because they have internalised that it will negatively impact their career. “I deal with young black artists who won’t speak about their blackness, because they have been told at art school that they shouldn’t. Art schools usually encourage students to be original by exploring their identity in their art, but this doesn’t apply for black kids,” she says.

“Better to be black in a country you’re not born in”

Wetsi Mpoma, who is 44, has dreamt of opening her own gallery since she was an art student, but it “wasn’t supposed to happen this way”. She had her professional path all planned: she would find a permanent job in a gallery, and then one in a museum or another cultural institution, where she would perfect her craft as a curator and learn the trade before opening her own space. After her master’s in non-European civilisations and art at the Free University of Brussels (ULB), she found an assistant position in a gallery in New York, Gallery 317 in Manhattan.

Wetsi Mpoma at her gallery in Brussels.

“I’m a fan of visual arts, of jazz and hip hop, so it was amazing. And as a black woman, it was heaven,” she recalls with a smile. “There were black people everywhere, on every layer of society.” This was 2007, and Barack Obama, then a senator for the state of Illinois, was running for president, sending a message to all black people of America and beyond with his campaign slogan: “Yes, we can”. “It was so exciting”, she recalls. But she’s aware of her tainted glasses: “It’s always better to be a black person in another country than the one you were born in, because the dominant system doesn’t see you as black: they see you as a foreigner, which is positive.”

Finding a job in Belgium was another matter. She freelanced, partnering on tours and exhibitions with Bozar, Wiels as well as the Africa Museum, but there was “always a good reason not to hire [her]”, she says: just like with housing discrimination towards Afro-descendants, she found that when recruiters said “We would like to hire black people,” it never meant that they actually did. She also realised that big museums and institutions asked for her input only on shows related to race: “I am an art historian, not only a black woman giving tours about black people!” Now, she would not take an institutional job – she values her independence too much. “I like having one foot in, one foot out.”

Anne Wetsi Mpoma has so many ongoing projects that she gets lost trying to list them. There’s the show she is curating for the Strombeek cultural centre, on the representations of the black female body, the book on decolonisation for which she has written a chapter about the arts, the monthly events and shows she is planning for the gallery, her project to act as an intermediary between African artists and bigger galleries in Brussels, among others. Opening her gallery is a risk worth taking, she says. “I see a need for that, in the art world, for black artists. And the fact that I am a black woman, curator and gallery owner, is important.”

By Pauline Bock