The pavements of Avenue Louise buzz with life. High-end stores, busy restaurants and prominent business offices stand together in a mosaic of luxury down the most prestigious avenue in Brussels.

Affluence and commerce have given Avenue Louise its celebrity status in the Capital of Europe, but deep in the more residential part of the avenue, there lingers an often overlooked, but equally important, part of Belgium’s history.

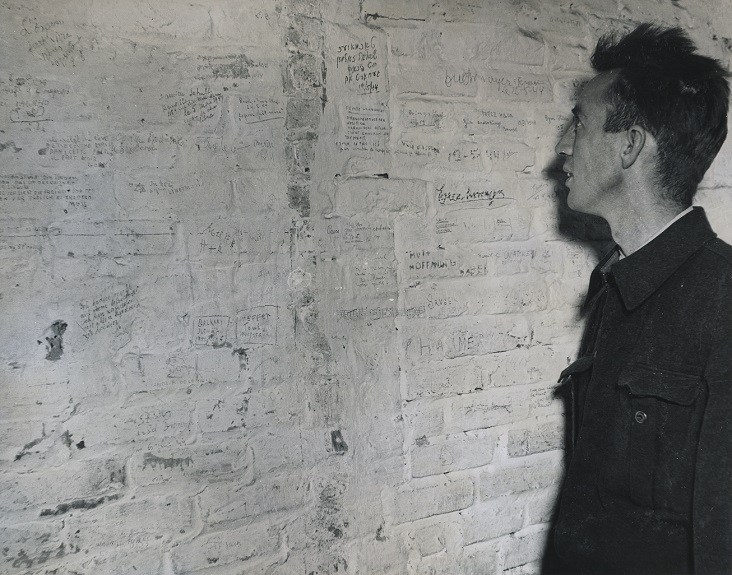

Down in the cellars of the buildings numbered 347 and 453, behind decades worth of coats of paint, the walls are engraved with messages by resistance fighters, political opponents, and Jews detained and tortured by the Sicherheitspolizei-Sicherheitsdienst (Sipo-SD), the Nazi security police, of which Gestapo was a part, during World War II.

For many Holocaust survivors who had resided in Belgium during the war, these buildings were the first place where they experienced the cruelty of Nazi Germany. They were then sent off to different concentration camps in Belgium and Germany, including the death camp in Auschwitz. However, many were killed before they could step outside and see the light of day.

Although all four buildings were occupied by Sipo-SD, number 453, also known as the Résidence Belvédère, was their headquarters following the German invasion of Belgium.

The occupation of these buildings, in particular, the most prominent and towering in Avenue Louise with 12 floors, was a strategic choice to display the Nazis’ power, said Chantal Kesteloot, a Belgian historian working with the Centre for Historical Research and Documentation on War and Society (CEGESOMA).

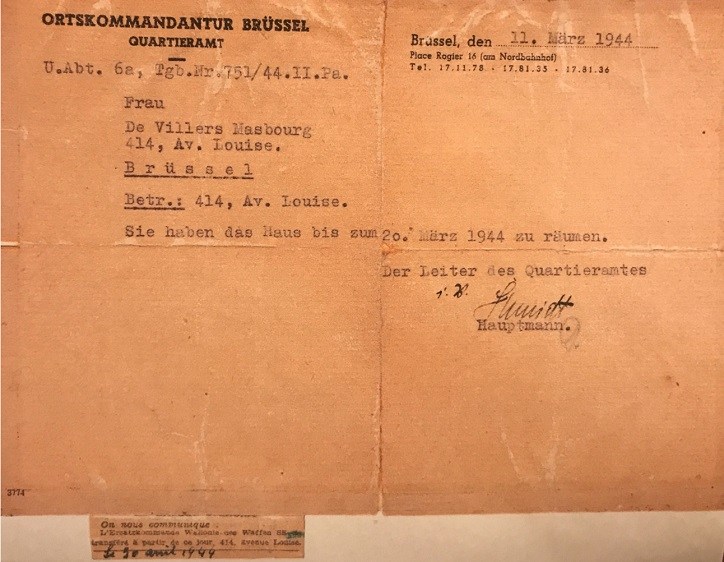

Eviction notice sent to the owner of Avenue Louise 414, Countess Marie Therese de Villers-Masbourg, in 1944. In it, she was told that the Walloon Waffen SS, the military branch of the Nazi party in Belgium, would occupy her home.

As for Avenue Louise, it was then, as it is now, one of the most prestigious avenues in Brussels, she added. It served as a place of significant strategy, not only for the Nazi party but also for resistance groups reclaiming the city during the liberation of Belgium.

In fact, even after Sipo-SD were evicted from numbers 347 and 453 after the liberation, the British took over these two buildings. This resulted in the further displacement of townhouse owners in Avenue Louise. Many of them did not regain access to their homes until the end of 1946.

Fight or flight

On 20 January 1943, the Sipo-SD suffered a blow to its foundation when Jean de Selys Longchamps mounted a solo attack on their headquarters. The Brussels native, a fighter pilot in the Royal Air Force at the time, flew his Hawker Typhoon straight at number 453 and bombed it, heavily wounding four members of the Gestapo and killing five. Among those casualties was Max Thomas, the deputy commander of the Sipo-SD.

It was earlier on that morning when de Selys Longchamps and a second pilot completed a mission in Ghent: bombing a train station. While the second pilot made his way back to England, de Selys Longchamps kept flying toward Brussels; he went over the city, passing the Palais de Justice, the Royal Palace, and the Cinquantenaire Park.

As he got closer to number 453, he descended, moving at 200 km/h, and faced his target straight on, bombing it close to the ground before flying back to a safer distance. The Royal Air Force often used this strategy called “Rhubarb”.

Having no explicit consent from his superiors, de Selys Longchamps was demoted for his unsanctioned and risky solo mission, but it also earned him the Distinguished Flying Cross, a military decoration awarded to officers who have displayed courage in combating the enemy.

Following the plane attack, the Sidi-SD temporarily moved to Queen’s Residence before resettling their headquarters in number 347 Avenue Louise where they continued to interrogate and torture Jews, resistance fighters, and political dissidents until the liberation of Brussels in September 1944.

De Selys Longchamps showed the Belgian people that “something is possible,” said Kesteloot. “There is still hope.” However, she does not view his attack as emblematic of the liberation of Belgium, but rather as a symbolic action that profoundly affected the morale of the people.

“There were not many moments of hope during the occupation, but this was one of them,” she explained.

Brussels, too, has not forgotten de Selys Longchamps’s impressive act. Right across from number 453, there stands, proudly, a golden half-bust statue of the pilot.

Or it used to. Early on a Sunday morning, on 13 October 2019, the monument was left in pieces when an unidentified man under the influence of alcohol crashed his car against it.

Nonetheless, thanks to this recognizable monument, Belgians know the general history of Avenue Louise. But many still don’t know what lies beneath those headquarters.

Partially, said Kesteloot, the reason for this is that too many people died without telling their story. And those who survived faced much worse later on. When they eventually gave their testimonies after the war, they focused on what they suffered in concentration camps in Belgium and or Germany.

“Avenue Louise is only a small part of their story,” added Kesteloot. “While [in the headquarters], there was probably some hope. They couldn’t imagine what would happen later on.”

It was with this desire to preserve the memory of these buildings that they were classified as objects of heritage by the Brussels government in 2016.

To my resistant father

In 1995, when historian and filmmaker André Dartevelle was preparing his film “À mon père resistant”, he was particularly interested in the cellar of number 347. He wanted to know first-hand the journey that the victims of Sidi-SD had to take in order to later portray it on screen.

Dartevelle was granted access by the then owners to inspect the cellar. Although the walls had since been repainted, they still showed identifiable inscriptions in the plaster—names, messages and calls for resistance.

The other cellars, including number 453, he could not examine.

In 2007, the Auschwitz Foundation in Brussels received a proposal to participate in an international colloquium on the future of places of detention, concentration and extermination. They chose buildings 453 and 347 on Avenue Louise.

The foundation, too, wanted to commemorate these cellars, and so, the members sought the support of the Mayor of Brussels, Freddy Thielemans, and Charles Picqué, Minister-President of the Brussels-Capital Region.

However, numbers 418 and 510, which were also occupied by the Sidi-SD, have yet to be classified. The current owners resist having others come in to inspect their premises. There probably lie, unseen, additional markings on the walls of these uninspected cellars.

But no matter how often these walls are painted, what happened in Avenue Louise, and elsewhere in Brussels, cannot be erased. As Kesteloot said, “There are traces of resistance in these buildings.”

By Sheila Uría Veliz