The principal effect of the Brussels bombings on March 22, 2016, was to kill 32 innocent people and injure hundreds more. A secondary effect, harder to quantify, was to remove some illusions about the cohesiveness of Belgian society. The bombings made many Belgians face up to questions about the nature of their society. Six and a half years on, Belgium is certainly less innocent and probably less liberal.

Belgium was painfully conscious of international scrutiny even before the March 2016 bombings. Revulsion at the attacks in Paris on November 13, 2015, was compounded by suspicions that the Belgian police, security and intelligence services could have done more to prevent the atrocities if there had not been operational failures.

The accusation levelled against the country’s politicians was that Brussels was exporting terrorism to other countries in Europe. Discontented youth were recruited in the capital as foot soldiers for Islamic State (IS), also known as Daesh. Many Paris attackers had links to Brussels, notably the apparent mastermind, Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who was killed five days later in a shoot-out in Saint-Denis. Salah Abdeslam, who took part in the Bataclan attacks in Paris, fled to Brussels, where he was involved in a gunfight on the eve of the March bombings.

Links later emerged between Abaaoud and Mehdi Nemmouche, who had fought with IS in Syria. In May 2014, Nemmouche shot two Israeli tourists and two members of staff at the Jewish Museum in Brussels, the first terrorist attack in western Europe claimed by the-then newly declared IS.

Similarly, there were links between Abaaoud and a terrorist cell in Verviers. That cell was dismantled in Verviers in January 2015, when two IS fighters were shot dead and a third injured. At the time, this was claimed as a victory for the security forces. However, it raised more fears about the extent of the problem than it dispelled, as nine people were arrested in Molenbeek at the same time. The security lockdown in Brussels ten days after the Paris attacks was an admission that the Belgian authorities did not have the situation under control.

So, although the 2016 bombings were a dreadful shock, for many Brussels residents it was qualified by a weary sense of expectation realised. This had, we knew, been a while in the making.

Unity, for a moment

The country briefly appeared united in shock and grief. But there were notable cracks in the unity. When far-right hooligans came to Brussels for a publicity-seeking march, which turned into a policing debacle, Yvan Mayeur, the mayor of Brussels, sought to shift the blame on his counterpart from Vilvoorde, Hans Bonte, and Interior Minister Jan Jambon (Mayeur later retracted his claim that he had not been given warning).

Another point of recrimination was whether the Brussels metro should still have been running after the airport bombs had been detonated. Plainly, lines of emergency communication between different authorities should have worked faster. This was just one example of how Belgium’s multi-layered governance made it more vulnerable to the terrorist threat.

After the Paris attacks, I made myself unpopular in some quarters by writing: “In virtually every other European country, the fight against terrorism involves greater centralisation of power, people and money…But Belgium, in thrall to its linguistic politics, is moving in the opposite direction.”

Soldiers remained a presence at Brussels airport for months after the bombings. Credit: Belga

The Brussels bombings did not reverse that trend. Centralising power, expertise and money is still contrary to the Belgian way of doing things, which is to spread the goodies around.

But the politicians did catch up with some overdue legislative work. The law was changed to allow search warrants to be executed at any time of the day or night. The regions – in different ways and to different extents – began tightening up their control of mosques in a bid to improve education and clamp down on those peddling a destructive version of Salafism. But, as is often the case, the unknown is whether these laws will be adequately enforced.

The bombs prompted politicians to take the threat posed by disaffected urban youth much more seriously than before. Those who had grappled with the challenges were given more of a hearing – the likes of Bonte in Vilvoorde and Bart Somers in Mechelen – and more money was directed at community projects. But this is costly, difficult, long-term work. Its value is often appreciated only when things go wrong.

Belgium’s prison system has been badly in need of modernisation and reform for decades. Progress is desperately slow, even though prisons are a proven breeding ground for radicalisation. It doesn’t help that reform of Belgium’s judicial system is equally glacial. Cases still take too long to investigate and come to trial.

Reform of Belgium’s various police services is also overdue. There has not been sufficient consolidation of the local police forces in Brussels. The quality of police recruits to those local forces is still doubtful and the vacancy rate too high. There are some signs of progress: the expansion of the cycling corps in some zones of Brussels seems to have improved the enforcement of traffic and public order offences. But there has also been a constant supply of policing scandals that undermine public confidence.

New threats

Is Brussels more fearful than it was? The Covid pandemic has upset many of our earlier notions about generalised fear, but the city quickly recovered. That the terrorist threat has reduced since March 2016 is probably more down to the state of war in Syria than changes in Belgium.

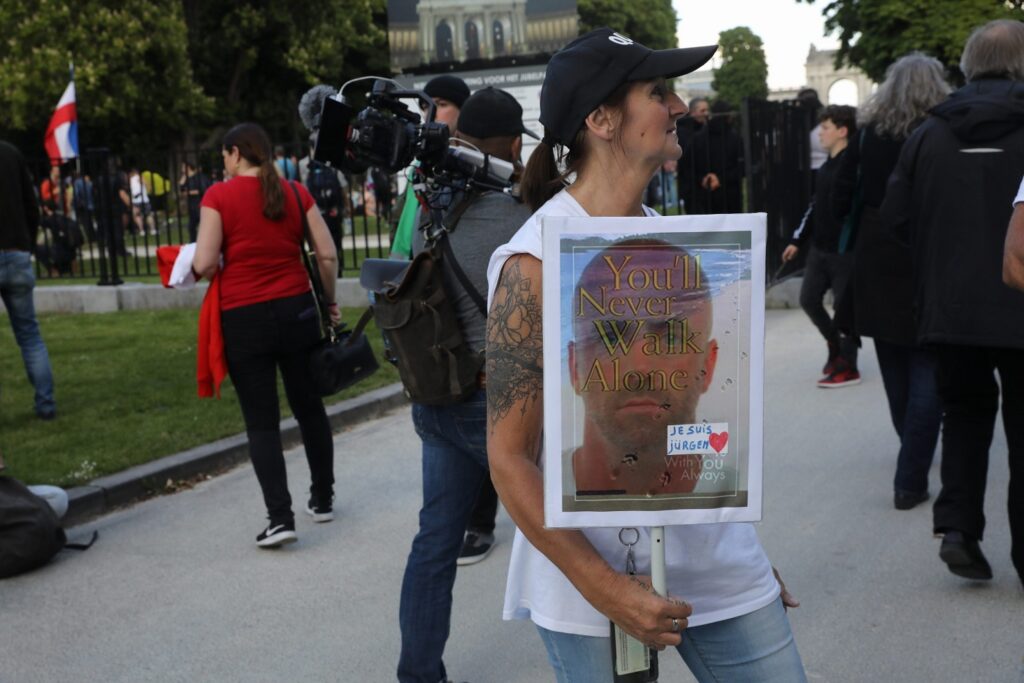

Different threats to public order have emerged. Last year, the greatest terrorist threat was briefly Jürgen Conings, a rogue soldier with extreme right-wing views who had issued threats to kill Marc Van Ranst, a virologist in the public eye during the pandemic.

Although warnings had been sounded about Conings’s beliefs and his behaviour, he continued to enjoy privileged access at an army base to heavy weapons. After a protracted fruitless manhunt, his body was eventually found by a cyclist a few hundred metres from where his car had been abandoned a month earlier. He had apparently taken his own life.

A support of Jürgen Conings, the errant soldier who was briefly a terrorist threat last year. Credit: Belga

More recently, the police and security forces have been preoccupied with organised crime, following explosions and shootings in Antwerp attributed to rival drug gangs. In May, representatives of the federal police and the office of the federal prosecutors told a parliamentary committee that they were unable to pursue some gang crimes, including serious fraud and violent crime because of a shortage of investigators.

The shortage of specialists was compounded when authorities cracked Sky ECC, a communication tool used by drug gangs. The breakthrough uncovered so much information about the international drugs trade that the police and prosecutors have their hands full pursuing a surfeit of leads for many months to come. “Since Sky, we’ve been living in another reality,” federal prosecutor Johan Delmulle told the parliament. Even after making allowances for prosecutors pleading for more staff and more money, one is left with the irony that the public is less safe because of successful international policing.

Like the fight against organised crime, successful counterterrorism requires good intelligence. Police and security services are increasingly turning to technology to provide them with evidence of crimes committed or about to be committed. That trend is a challenge to democratic, liberal societies because technology poses difficult questions about privacy and about how far the state can intrude into the lives of its citizens for the sake of the general good.

The old restraints on the powers of the state – limits on how long someone can be held for questioning, that quaint presumption that search warrants should not be executed in the middle of the night – were generally visible in the breach. But it is much harder to know when the state is abusing its investigative powers in pursuit of electronic communications. While Belgium’s liberal constitution provides theoretical protection against state over-reach, there is still a significant risk that, deliberately or accidentally, abuses will happen away from the gaze of the public, the press, or the statutory supervisory committees.

However, these threats to liberty are not expected to dominate public debate. Rather, it is much more likely that the assimilation of migrants will become a hot-button issue, exploited for various political ends. If that is the case, then the approach to 2024’s various elections – communal, regional and national – will be unedifying. If the bombings of 2016 have taught us anything, it is that political leaders should be devoting more time and attention to prisons and schools.