Until December 2022, the City of Brussels conducted much of its administrative business from the Centre Monnaie, the vast X-shaped modernist tower that looms over Place de Brouckère. The lavishly spaced but poorly maintained building dated from 1968, and visits were a weariness-inducing and impersonal experience for citizens in need of ID papers or a permit.

Access to officialdom, perched many threadbare floors above street level, meant taking an escalator to reach a bank of lifts where a polite notice suggested visitors use the stairs. A tarnished fragment of the Atomium’s original aluminium shell hanging in the marble-lined, double-height lobby was a reminder you were entering the discredited era of post-war Brussels modernism.

In June 2006, the City of Brussels decided to sell up, freeing the building for redevelopment as a hotel and apartments, reskinned for the 2020s. A call for tenders for a new home yielded a single serious proposal, just 80 metres away.

Vacating the Centre Monnaie, one of the last unreconstructed avatars of the much-vilified Brusselization process, the administration would build Brucity, its new seat of government on the site of one of the most infamous survivors of that phase of urban upheaval, the semi-abandoned hulk known as Parking 58. This manoeuvre would correct the errors of the recent past in a serendipitous two-for-one deal.

However, those errors stretch back far beyond the 1950s. The new glass mammoth stands on the site of not just a car park but before that, a dog track, an ice rink, a ballroom, a covered market, a fish market and the city’s original port on the vanished river. A location emblematic of the struggle to balance the needs and wants of citizens with the trade to sustain them. The latest chapter of the history of Brussels is written on the site where its first chapter opened.

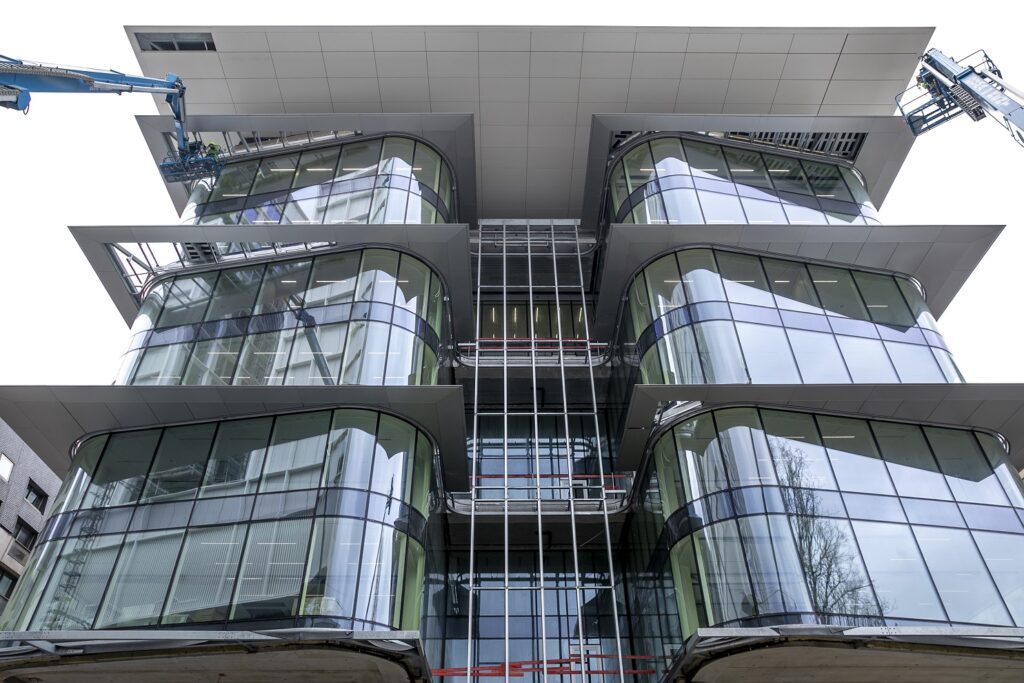

Brucity, from below the front

Occupying an entire city block parallel to the central boulevard, Parking 58 was a Portuguese man o’ war of a structure, uniting a car park, offices and a mothballed supermarket. By the time the city cast its eye on the site, it was covered in a cladding of an architectural style best described as eyesore. Its demolition revealed the foundations of several predecessors on the site, including a medieval quay. Construction of the new building was halted for six months as archaeologists were given their first and final opportunity to document the site that arguably marks the spot where Brussels was ‘born’.

Modern showcase

Like its predecessor, the city’s new home takes up an entire city block and on an even larger scale over its eight floors. Brucity contains around 60,000 square metres of space, of which 37,000 are dedicated to offices. In an inversion of the previous situation, parking is pushed underground, over four levels. There are 560 spaces for cars, close to the capacity of Parking 58 in its final form.

Brucity unites virtually all the municipality’s activities under one roof. It not only provides administrative services for Brussels residents but also houses offices for city councillors and a new debating chamber at the top of the building. Study spaces and meeting rooms for citizen associations are promised, and a restaurant may open on the eighth floor once a concession is awarded. This means a new life in retirement for the medieval Hôtel de Ville on the Grand Place after 600 years of service. While the historic building will still host weddings and municipal receptions, it is now effectively a museum.

The exterior of Brucity, which claims to be a passive structure, is almost entirely triple-glazed glass, presumably implying transparency in government. In summer it will be cooled using sewer water via a heat-exchange. The building is rounded off at its four street corners and the entrance bays, save for the floors dividing the storeys. Projecting into space and preserving the squared-off contours of an earlier, boxy design, these appear to slice through the entire structure like the flat blades used by magicians to saw the lady in half.

The old parking 58 is torn down

Brucity is vast, occupying as much of the cramped rectangular site as its predecessor Parking 58 and rising even higher, thanks to an exemption on building-height limits. Too big to take in from the narrow streets forming the perimeter, it is perhaps best appreciated from a block away on Boulevard Anspach at the mouth of Rue du Marché aux Poulets: at dusk, moodily lit by low-energy LEDs, its bulk and curves give it the allure of a streamlined art-deco interwar liner freshly arrived in port. As a waggish Twitter user observed just after the inauguration: “I wish Brussels would learn from Venice and ban cruise ships from the city centre.”

History in its foundations

The shipping analogy is fitting. The very spot where Brucity’s façade overlooks Rue du Marché aux Poulets as it meets Rue Sainte Catherine is the location of the medieval bridge or Scipbrug which carried the historic high street of Brussels, the steenweg, over the Senne river at its highest navigable point upstream. Behind that façade was once the portus, the original port of Brussels, at a crossroads marking the birthplace of trade here by water and land, both local and international, and thus, arguably, of the city itself.

As stated in the Brussels, City of Art and History series of pamphlets, published by the region in 2000, this is a location “of the first importance in the history of the development of the city…where Brussels makes its first appearance in commercial history.” Indeed, as well as the 14th century stone quay, the archaeologists discovered even older structures in wood, objects dating back as far as the 7th century and proof of another tributary of the Senne.

The archaeological finds

The medieval quay, or werf, lay undisturbed on the site for centuries until the diggers carved out the underground car park for Brucity in 2018. Before the 20th century, when reinforced concrete basements penetrated further below ground than buildings of previous ages had stood tall above the surface, cities developed in layers. Each subsequent redrawing of the palimpsest bore the remains of its predecessor, leaving the long-obsolete werf to a centuries-long slumber many metres below the surface.

Fish market on the boulevard

In the mid-16th century, a new canal was completed to the west of the werf. It allowed Brussels merchants to bypass the sluggish, winding Senne and avoid the tolls on that route charged by Mechelen for passage to the Scheldt and international markets. As heavy trade shifted to the city’s western periphery, the municipality saw a chance to ease traffic in the centre by moving street traders to the now semi-deserted riverside. A fish market was built on top of the former dock at the beginning of the 17th century.

Contemporary painting of the werf

By 1825, modern hygiene requirements as well as civic pride demanded certain improvements, and a new, larger fish market was built here on the right bank of the Senne. The stalls were housed beneath a handsome colonnade curving around a fountain and from a new pavilion the catch was auctioned. To the east of the site, along Rue des Bateaux (literally Boats Street), some of that catch was immediately fried and served in the numerous estaminets serving the market workers. To the north, a Marché aux Moules (Mussels Market) sold shellfish and, at a discount, ageing fish condemned by the market authorities.

This second version of the fish market was short-lived. By the 1860s, the City of Brussels launched a colossal 25-point civil-engineering programme to modernise the downtown. As part of a new waste and water network, the now-irrelevant, flood and disease-prone Senne was buried underground. Chief among the new features above ground was a wide boulevard imitating the Paris of Haussmann. Just enough land would be expropriated and razed to make room for the new street and two major monuments. One of these is the Bourse, the stock exchange, completed in 1873 and which still stands on the eastern side of the boulevard: as it celebrates its 150th anniversary in 2023, it is being converted into a new attraction on the theme of beer (and, unlike the Brucity site, the archaeological remains underneath, this time of a 13th century Franciscan monastery, are being preserved).

Paris on the Senne,

For the western side of the grand new street, the city envisaged an enormous covered market complex with eight pavilions arranged in two parallel rows, like the famed Les Halles in Paris, first opened in 1857. For its version, Brussels wanted a 165-metre frontage on the new thoroughfare on a site 95 metres wide, covering over the river Senne and the fish market on its bank.

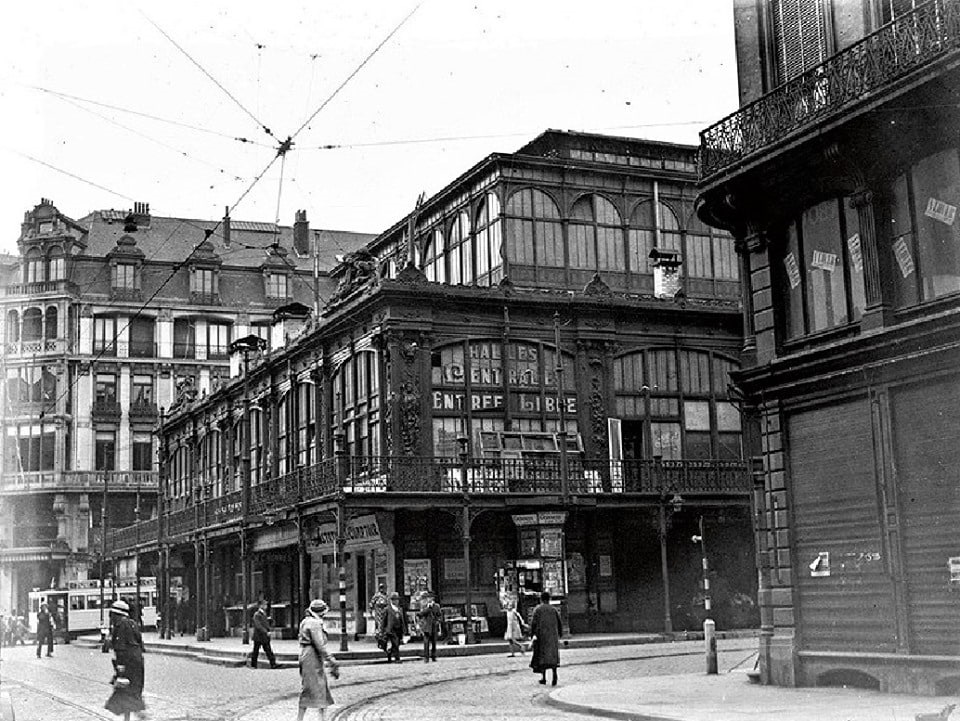

The old Halles Centrales market

Under a public-private partnership agreed between Mayor Jules Anspach and the Belgian Public Works Company, the city would gift the land and a large subsidy to the English firm to build the 16,000-square-metre facility. However, the anticipated contribution from the national government was refused and the plans were scaled back. In 1871, shortly after a fiery intervention from an opposition councillor casting doubt on the viability of the project and accusing the City of being in collusion with the Belgian Public Works company, the English company was liquidated in a cloud of financial impropriety.

The City became the outright owner of the whole project. However, just two of the eight pavilions were built, in a cramped back-streets site and the more prestigious half of the cleared site fronting the street, now Boulevard Anspach, was allocated to Paris-style apartments and the now-vanished Grand-Hôtel. Brussels was stuck with the footprint of a never-built phantom behemoth that continues to shape planning even now.

Both halves of the site struggled to thrive after the failed market plan. The apartment blocks attracted few buyers and ended up remaining the property of the city. The new Halles Centrales market, completed in 1874, was designed by Léon Suys, the master architect of both the bourse and the wider scheme to replace the river with modern buildings.

The ornate design, with its stone base and metallic structure depicting market produce in cast iron echoed its much larger counterpart in Paris. It also presaged the arrival of Art Nouveau architecture a couple of decades later, ushered in by the new department stores, also with iron facades, such as Old England (now the Musical Instruments Museum) and Victor Horta’s Innovation nearby in Rue Neuve.

Competition from such new shopping attractions proved too fierce. In 1893 the city converted the northern pavilion into a hybrid entertainment complex featuring an ice rink called Pôle Nord in winter and a concert venue branded Palais d’Été for the rest of the year. In 1933, amid a global depression, the southern pavilion was converted to a new concept, a branch of the cut-price department store chain Priba (lo-cost), itself owned by Innovation.

Downfall of downtown

After a spell as a theatre, the fortunes of the northern half of the market followed the socio-economic descent of most of downtown Brussels, hosting boxing matches and, after the Second World War, dog-racing.

As the 1950s progressed, it was the turn of the wider Brussels area to undergo huge infrastructure work aimed at harnessing Expo 58 as a boost for the national economy. With Belgium turning its gaze this time across the Atlantic for inspiration, the main stimulus project for downtown Brussels would be a US-style parking garage. The city gave its developers a 70-year lease on the site of the northern pavilion, which was torn down and replaced by the initial section of Parking 58, a modern, multi-storey structure inspired by a garage in San Francisco.

Belle Epoque Place de Brouckère

This co-existed for several years with the shabby but still ornate remains of the southern pavilion but, after a slow start as Belgian drivers became accustomed to the concept of self-service parking, the garage gained extra floors and the city granted a fresh 70-year lease to developers who demolished the remaining half of the market. The two halves of the site were then combined in a single structure which as well as cars, hosted government offices and, at ground level, shops and a supermarket.

While much reviled in its later years, the Parking 58 building was prized for one thing above all, the views over Brussels from its vast flat roof, long prized as a venue for illicit, and later, as demolition approached, officially-sanctioned sundowners.

Parking 58

Ecologically-minded politicians and citizen groups called from the start for free public access to the roof of the city’s new HQ. When it opened in December 2022, with surprisingly little fanfare for such a vast new structure, this was not the case. Brucity’s main entrance is on the grimy and semi-derelict rue des Halles, which the city has promised to clean up, along with the rest of its perimeter over the next 18 months, planting trees and removing street-level parking.

A curvaceous, Instagram-friendly lobby rises through the full height of the building and is lit naturally from above. Access to the upper floors and roof is via two small glass elevators which must be activated by a QR code. A video posted by a city councillor on YouTube shows a rooftop promenade covered in wooden decking bordered with shrubs.

Access to the large, open-plan reception areas on the ground floor of Brucity is open to all comers. The appearance is not unlike a modern retail space, such as Coolblue. Brussels residents can book appointments for municipal services obtained on the upper floors via touchscreens which issue the QR codes to activate the lifts.

Brucity’s lobby occupies the site of the short road that historically linked the main boulevard to the Sainte Catherine area through the middle of the block. Those hoping this path would be resurrected for public access will be disappointed: out of office hours, such a trip requires a detour around the whole site.

Back to the future?

Brucity’s first city council meeting, in the new eighth-floor chamber with more space for public attendance, took place on January 16, 2023, just 300 metres from its now-mothballed predecessor.

Proximity to the historic building in a place within the downtown nucleus of Brussels, the so-called Pentagon, was one of the requirements of the tender offer launched for the new administrative centre in 2006. It’s not clear why this location was a requirement. For over a century, the limits of Brussels City have stretched as far as eight kilometres away to the north and seven to the southeast, as shown on a stencilled metal map of the municipality rising six storeys above Brucity’s entrance.

Why the need to shoehorn the building into the exact same space as Parking 58 and gamble that its architecture will distract from its bulk any more than that of its predecessor? Could a space not have been found in the nearby Northern Quarter, an area devastated in the late 1960s by the failed Manhattan Project promoted by the same city councillor, Paul Vanden Boeynants, responsible for Parking 58 in the first place? An area infamous in the national media for its neglect, where the increased footfall would have been appreciated and where new tram and metro lines are due to arrive over the coming years.

Posterity will judge Brucity’s design, as eye-catching in its 19th century surroundings as Parking 58 (initially much admired by the architectural press) was in its day. However, the choice for location the first monofunctional building on the site since the failed market of the 1870s, is more questionable.

While it may be delightfully bright inside the new glass mammoth, it sucks light from its surrounding streets just as its predecessor did, leaving them with the feel of canyons. Planning rules can be accommodated to allow a development to extend vertically up or down as far as technically feasible but cannot change its horizontal constraints.

For campaign group ARAU, which had called for a city park on the roof of the new building, the project “appears to have sprung directly from the 1950s: more offices and more parking in the form of a monolithic block in denial of and crushing the urban tissue that surrounds it.” It adopts the footprint of the compromise design that emerged from the debacle of the 1870s Halles, a development that sprang from the 1850s. And on a site that repeatedly failed through each cycle of demolition and repeats mistakes on the same theme.

Perhaps worse, it obliterates the cross-street that gave a lightness to that ill-fated covered market, replacing it with a dead end to Rue Grétry, which previously led to Sainte-Catherine through the market from the Îlot Sacré, the ancient heart of Brussels around the Grand-Place.

Collective imagination

In an article on Parking 58 in the Brussels Region’s own magazine on the built environment, published as the building’s demolition became certain in December 2014, architect Sven Sterken suggested that the building’s nature as a semi-public space within the dense, privately-owned and thus inaccessible mesh of the hypercentre had made Parking 58 “a sort of freeport in the collective imagination of Brussels…the historic role of the site in the development of Brussels demands for the future an ambitious urban construction which does more than just serve…a select group of inhabitants and users.”

Harnessing that collective imagination to the fullest, might the solution for this historic site have been to build nothing? For 150 years, this narrow slice of real estate has failed to deliver consistent profits for anyone other than developers. Its transformation into a purely public building implicitly recognises this truth.

The Brussels of Anspach outsourced greenery to the suburbs while concentrating trade and consumption within the heart of the Pentagon. But in an era when commerce could be ruled out in the location, the site of the historic port of Brussels, could a mini Central Park for Brussels not have been contemplated?

Greenery, water run-off, sunlight, a place of recreation for Brusseleirs and tourists to gather away from traffic and shops: such are the stated ideals of both the City of Brussels and its region for the 2020s. The origin of the city itself, the werf, could have been preserved as a modest and thus authentically Brussels monument at the bottom of a park, landscaped to recreate along its 160-metre site the course of the Senne river, fulfilling another ideal cherished by the authorities. With another major project, the Dome, soon to link the redeveloped Bourse to Brucity, such a park could have led the eye and the feet up the historic northern exit from Brussels, rue de Laeken, towards its present, the new developments along the canal, and the next chapter in the story of Brussels, the forthcoming modern art museum.