Belgium has a big birthday coming up. In 2030, the country commemorates its bicentenary and in Brussels at least, the main venue for events will be the park in the east of the city where it held its fiftieth.

The Cinquantenaire, named after the 1880 golden jubilee (it is called Jubelpark in Dutch) will see its existing and somewhat dusty attractions, the Art & History Museum, the Military Museum and Autoworld, spruced up and adjusted to modern tastes.

The federal government is providing an initial €155 million in funding, and in seven years a thorough restoration of the flora and monuments dotted across the 34-hectare site should be complete. Most exciting of all perhaps is a proposal to cover the urban expressway that scythes a 190-metre-long cutting through the centre of the park.

However, while organisers want the Cinquantenaire to be an inspiring example of modern design, they reject what they call “post-Bilbao starchitecture solutions” – referring to the Basque city’s introduction of a spectacular museum to draw in visitors. This is not least because the park is a protected monument in its entirety.

The resulting proposals for the road-covering suggest it should be both eye-catching and invisible. As elsewhere in the city, the paradox of the road tunnels of the cars-everywhere age threatens to hijack plans for a gentler, more human-orientated future. Too expensive to remove, they are too unsightly to ignore, but with the 19th-century appearance of the park largely frozen since the tunnels were completed in the 1970s, leaving them be could be less controversial than covering them up.

Overlaying any material upgrades meanwhile will be a symbolic reimagining of the Cinquantenaire site. The project was presented to the press in April 2023, an event attended by the federal secretaries of state responsible for the national institutions, the minister overseeing Brussels’ infrastructure, the president of the Brussels region and the mayors of the two communes in which the park sits, Etterbeek and Brussels City.

In line with local traditions dating back to the tunnel era, the references were American. As befits the political capital of a federal state, the Cinquantenaire will become a ‘National Mall’ evoking Washington DC. Alternatively, as befits the cultural and economic capital, journalists were invited to present the scheme as ‘Central Park’, evoking New York City.

The Moonshot

Europe is invited too. The European Commission wants to associate itself with the covering-over of the road tunnel, where it detects an opportunity to make its “achievements more accessible and tangible to the public.” The Belgian government hopes the Commission will pay for this part of the scheme. It is already funding the plans to reorganise the Schuman roundabout a few steps away from the park and believes that together, the sites “could serve as an ‘agora’ to discuss the past, present and future of Belgian society and its place in the European family of peoples.”

The arch, in it's splendor

An EU-funded Cinquantenaire/Schuman axis could also form a section of the Brussels Region’s concept of a ‘Green Museum Mile’ snaking south-west along Rue Belliard/Belliardstraat to Leopold Park and west along Rue de la Loi/Wetstraat to the Park of Brussels and the Mont des Arts beyond, at the fringe of the historic city centre.

The Commission describes all this as “walking the talk,” and Belgian Prime Minister Alexandre de Croo called the project for the park a “Moonshot”. How will everyone keep their feet on the ground while reaching for the stars?

The park, from above

With so many cooks, local, regional, national and supra-national, gathering around such a rich broth, the government prudently appointed an ad hoc committee to liaise between them and steer each vision to create a cohesive whole ready for bicentenary year, both in terms of constructions and events.

The Horizon 50-2030 committee’s masterplan aims to place the Cinquantenaire among the top five most-visited attractions in the Brussels region, thanks to “the most ambitious heritage project in Europe.”

Problematic monuments

As the 2030 horizon closes in, it is perhaps the heritage challenges that threaten to stir the pot. The entire site was listed as a protected monument in 1976, shortly after the expressway cutting through it was completed.

Among the protected contents of the park are some highly-problematic monuments that celebrate Belgium’s colonial ventures in Congo. An official report by a special commission on “The Decolonisation of Public Space in the Brussels-Capital region” published in July 2022 addressed their future but its conclusions were kicked into the long grass. There is less appetite for that discussion of Belgium’s past than the report’s authors hoped for.

The Robert Schuman bust next to the General Thys memorial

As things stand, a 1964 bust of one of the EU’s founding fathers, Robert Schuman, sits cheek by jowl with an allegory of Belgium guiding the Congo, a memorial to General Thys, a businessman and key figure in Leopold II’s imperial schemes. Winged train wheels flank its base, in reference to his role promoting rail in the colony.

Between them, inscribed on a bronze medallion, the general’s face gazes west towards the city, a few steps away from that of Schuman, who is doing the same. Is this juxtaposition, this cohabitation, one of the sustainable and cohesive solutions the EU wants to put its name to?

The throughway that rises into the park

With such statues and the rest of the site considered protected monuments, the Royal Commission for Monuments and Sites (CRMS in French, KCML in Dutch), a panel of specialists in the built environment, must be consulted over any plans.

That includes interruptions to the view Thys and Schuman are enjoying, the historic perspective into central Brussels and one of the original features of the site dating back to its creation. The CRMS already signalled this as a priority when it opposed a nearby redevelopment plan for the Schuman roundabout. The developers of the 2030 project enjoy anything but a free hand.

Blank canvas

The historic nucleus of the Cinquantenaire site, dating from 1880, is the monumental hemicycle and its attached wings. These were designed by Gédéon Bordiau, an assistant to Joseph Poelaert on the gargantuan Palace of Justice project and whom he had succeeded as architect to the City of Brussels.

Unlike his mentor, who infamously razed an entire working-class neighbourhood for the new law courts, Bordiau was working on a blank canvas on the edge of a new suburb. The site chosen was a wide, flat expanse created a generation earlier as an exercise ground for the army, which had departed in 1876.

Budget restraints defeated initial plans for a Universal Exposition and Bordiau’s brief was to create a suitable frame for both the independence ceremonies of the summer of 1880 and a dual exhibition on Belgium’s achievements in the fields of art and industry.

With just two years to prepare and with construction only starting in May 1879, the deadline was missed. Only the two exhibition halls and the base of the colonnade were complete when the festivities began. Painted canvases and plaster models held up by wooden frames filled in the gaps.

The centrepiece of the 1880 celebrations was a ‘fête patriotique’ held on August 16th commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Belgian Revolution. Artillery salvos were fired from 8am until nightfall. Painters hoping for public commissions stalked the grounds that day, taking preliminary sketches for canvases that years later would remember the timber stage set as stone galleries capable of supporting teeming crowds.

The lavish celebrations Belgium's 'Fête patriotique', in 1880, including veterans of 1830

Guests of honour included the few surviving veterans of the uprising against rule from the Netherlands and aged signatories, both liberal and Catholic, of the 1831 constitution. Old political foes reconciled in a symbol of national unity at the festivities by an ancient rail locomotive.

The 1835 engine, Belgium’s first and, more importantly for national pride, mainland Europe’s first, elicited “a tender devotion” among the crowds. “It was revered as a symbol and as guarantor of the as-yet-undefined progress of the future,” according to the historian Henri Pirenne writing after a further 50 years had elapsed, at the time of the centenary.

That future quickly took shape. Five years after the intimate and inward-looking celebrations of a small country’s resilience, its second monarch, Leopold II awarded himself personal rule of an area of central Africa 80 times the size of Belgium.

Universal values

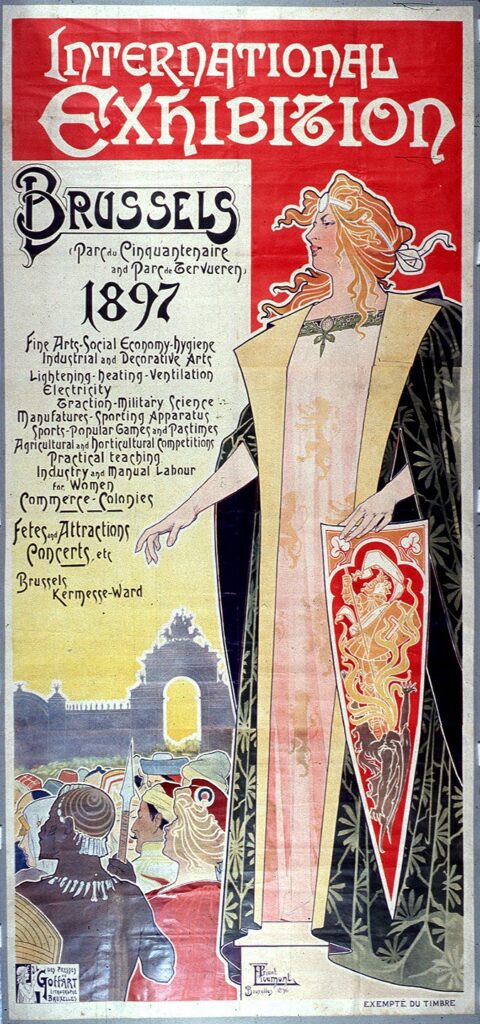

The high tide of the Cinquantenaire as a venue for the national pageant arrived in 1897 when Brussels, its economy transformed by the acceleration of free trade in Europe and by Belgium’s activities in Africa, finally hosted a Universal Exposition.

Poster for the 1897 International Exhibition, held in the park

The original plan before the 1880 celebrations had been to retain a small central section of the park as gardens around a decorative arts museum and develop the rest of the vast site as high-class housing. Mapmakers published views showing a belt of phantom streets decreed by the Brussels town council around the site and named on the theme of the proposed museum: lace, ivory, jewels and marquetry. However, the success of the 1880 national exhibition convinced the state to expand the site instead.

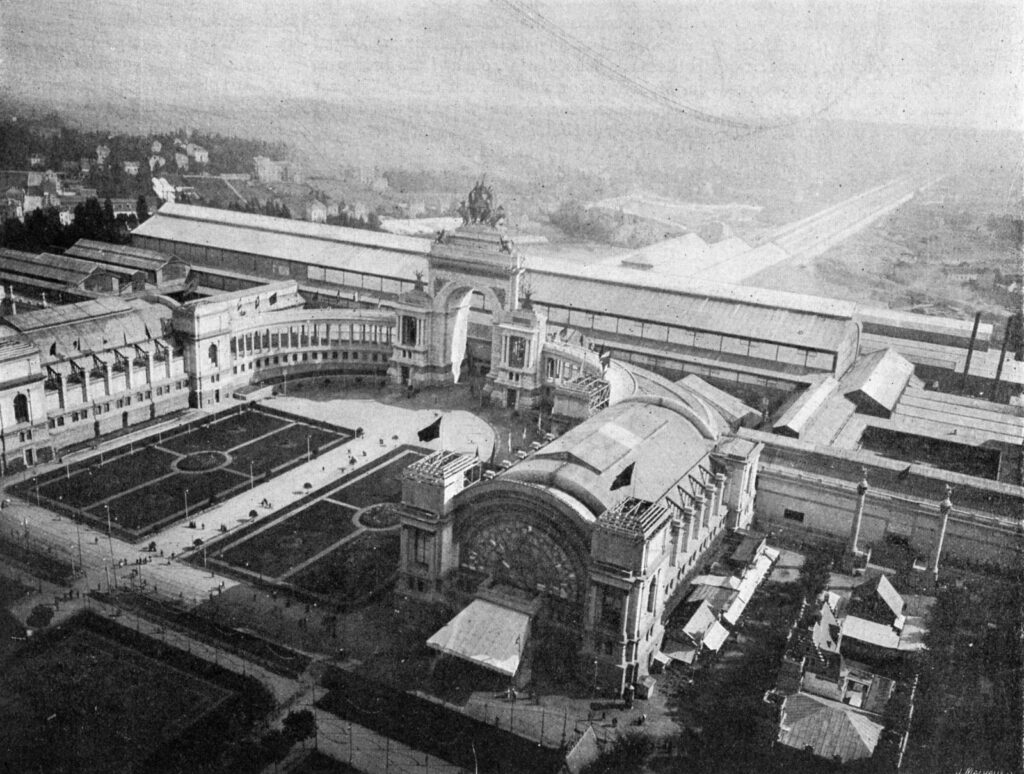

View east through unfinished Cinquantinaire arcade, before 1905. The huge Quenast stone columns were later knocked down to make way for the tunnels

For the 1897 events, the park, confirmed in its present-day pentagon, retained certain existing monuments from the earlier festivities, such as the two enormous columns framing the colonnade and supplied by the porphyry quarries of Quenast. New ones were added to showcase Belgian materials and craftsmanship.

The temporary Cinquantinaire arcade designed by Gédéon Bordiau, in a photo from 1888

Instead of new streets at its west end, the park gained Horta’s Temple of Human Passions, a circular building housing a vast painted Panorama of Cairo (now the Brussels Grand Mosque) and twin stone exedras to promote the quarries of Hainaut (these benches are now a popular backdrop for TikTok videos).

The missing piece however was a permanent triumphal arcade joining the two sides of the colonnade and closing the vista along Rue de la Loi from central Brussels. As Leopold’s debts racked up in anticipation of rewards from the Congo Free State, insufficient funds and a strike among quarry workers meant that once again, a plaster mock-up was deployed in 1897 to complete the unfinished arch. A painted canvas depicted a quadriga, a classical chariot, on top of the temporary monument.

Dynamite

It was thanks to modern chariots that Leopold would finally overcome his debts and complete the cherished arcade. The new global automobile industry had an insatiable thirst for natural rubber, a resource that the king’s African possessions could produce in abundance.

Unexploited land across the colony had been nationalised and divided into concessions granted to private companies set up to organise production. The crown retained one of the largest zones and a hitherto unpromising enterprise began to yield vast profits.

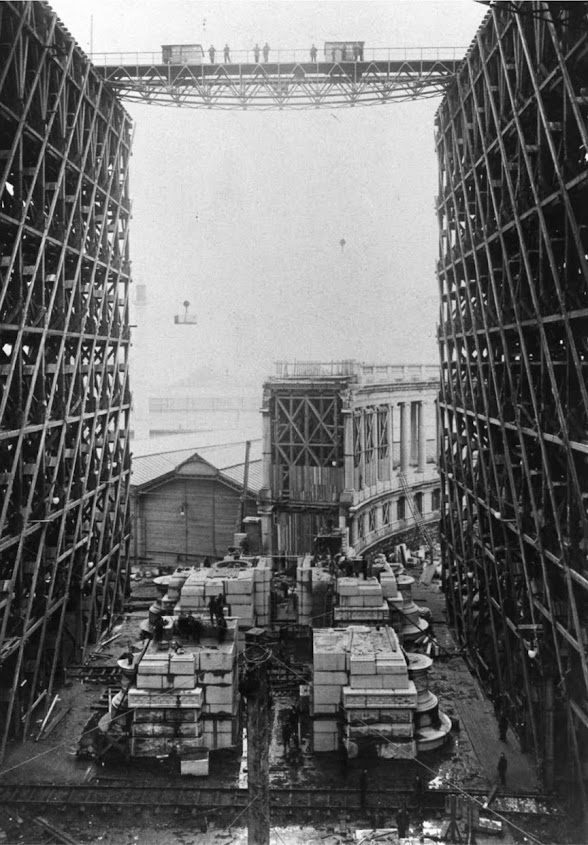

Construction of the new arcade in 1904

With his credit repaired, Leopold hired Parisian architect Charles Girault to complete the arcade. Girault dynamited Bordiau’s uncompleted work and in just nine months the arcade we see today was built in Belgian blue stone, ready for the commemoration in September 1905 of the 75th anniversary of the Belgian revolution.

Thomas Vinçotte, who would later add a controversial tribute to the Congo pioneers to the monuments in the park, sculpted a new quadriga representing the province of Brabant and finally cast it in bronze.

But the wheels were about to come off Leopold’s private empire. The rubber concessions were responsible for some of the worst abuses in the colony, relying on forced labour to meet production targets and punishing resistance with mutilation.

International protests multiplied and in 1905 as Girault rushed to meet his construction deadline, Emile Vandervelde, the socialist leader in parliament, referred to the project as “what people will perhaps one day call the arcade of severed hands”. Three years later, Leopold surrendered private ownership of the Congo Free State, which was annexed by the Belgian state.

Sunset over the Cinquantenaire

As the sun set on Leopold’s personal empire, the Cinquantenaire, by now surrounded by prosperous inner suburbs, entered a period of semi-retirement as a venue for events. For Belgium’s next Universal Exposition in 1910, it played second fiddle to a more spacious site in Solbosch to the south (now the university, ULB).

For the 100th anniversary of independence in 1930, plans for a Universal Exposition in Brussels were drawn up for the Heysel Plateau in the north and the Boulevard du Centenaire was named for the occasion. The event was cancelled however, to allow Liège and Antwerp to hold centennial events, and Brussels instead hosted a Universal Exposition in 1935 in unrepentant commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the Congo Free State as well as for the 100th birthday of Belgian rail (the first locomotive was wheeled out once again).

The controversial monument to the Congo pioneers

For the Cinquantenaire, meanwhile, 1930 ushered in a new role for its buildings as repositories of the past and for its grounds as a neighbourhood park. The revival that year of the medieval Brussels Ommegang folklore parade culminated here as work on the Art & History Museum neared completion.

Writing at the time of the centenary, Henri Pirenne asserted that it was "impossible for the current generation to grasp the effect on those who attended in 1880”. By the time Belgium reached 150 in the 1980s, that “current generation” looked back on the Cinquantenaire of 1930 as an already dusty, if beloved suburban playground.

In their book Cinquantenaire Park, a dreamlike, post-surrealist evocation, the writers Marcel and Gabriel Piqueray recalled their childhood as twins growing up in the area in the years leading up to 1930. Discreet bordellos lined the surrounding streets and the boys fetched beer for nanny at the farm-turned-guinguette at the corner of Avenues de Cortenberge/Kortenberglaan and de la Renaissance/Renaissancelaan.

Much as children of today, they toured the attractions of the park waffle in hand: the “prison tower” and the twin columns “erected to the glory of Quenast stone". As they passed through the colonnade, they would breathe “Leopold II passed through here,” and on a summer evening make their way up Avenue de Tervuren/Tervurenlaan, pausing at what would become the Montgomery roundabout to look back at Brussels. “Directing your gaze to the left, you could make out very distinctly the arcade of the Cinquantenaire crowned by the quadriga where the horses’ heads watch the light of day descend along the Rue de la Loi,” they wrote.

The trench

That historic view is an intangible obstacle for the 2030 organisers. Along its axis is a trench cutting through the park, where the entry ramps of two traffic tunnels meet (one emerging from under the Schuman roundabout and built in the 1960s and one from the 1970s plunging under the arcade to Avenue de Tervuren).

Before they were built, cars simply drove through the centre of the park and between the arches. The Piqueray brothers recalled their father being driven through Girault’s sumptuous arcade in a stockbroker pal’s luxury French car, an Avions Voisin (an example can be seen in Autoworld). The next day, the stockbroker was in jail.

The Quenast columns were toppled, somewhat criminally, to make way for the tunnels (no plans appear to exist to reinstate them). Until the end of the 20th century, the hump where the two ramps meet was at more or less ground level. Since then, the expressway they form together has been surrounded by a low wall and masked by a surprisingly effective hedge.

Flattening the two ramps in order to truly bury the roadway isn’t feasible: it would be a costly way of creating an additional stretch of lawn, and besides, the metro is directly underneath. Instead, the regional development agency Urban.brussels proposes that a new structure up to six metres high and 40 metres wide could fully or partially cover the trench.

Designing such a structure is the object of a call for designs from young architects organised by the European Commission as part of Europan 17, the flagship element of the EU’s New European Bauhaus (NEB) initiative for the built environment.

However, there is the cherished view recalled by the twins. The new structure would stand in the centre of the historic perspective from the arcade down the length of Rue de la Loi. This makes it guaranteed to be opposed by the CRMS, which has been battling to preserve this view for a century.

In 1938, it opposed the construction of a tall apartment block on the corner of Avenue de la Joyeuse Entrée/Blijde Inkomstlaan and lost (the building, now listed, is the only pre-World War Two survivor remaining on the street).

More recently, the CRMS issued an unfavourable opinion in April 2023 over the plans for a massive canopy at the Schuman roundabout. It said it wants to “avoid repeating the error of judgement” that allowed The One, a tower rising 94 metres above Rue de la Loi, to nudge its QR-code looks into the view through the arches of the Cinquantenaire from Avenue de Tervuren.

Smoke and mirrors

Urban.brussels says a structure over the trench could be clad in reflective panels, taking such a design cue from the 2021 Tondo, an enclosed footbridge in the form of a giant roll of sticky tape attached to the federal parliament building in Rue de Louvain.

However, the reflective underside of the proposed Schuman canopy failed to win over the CRMS. If the CRMS’s objections mean the scheme is blocked, this could leave the 2030 Cinquantenaire plan without a centrepiece. But the EU would also have plenty of wiggle room to refuse to fund a cover for the trench.

As the Europan briefing note says: the aim is to create “an axis to be seen as a cursor line generating diverse relations. A covering or a catwalk above the tunnel has to be seen as a result of these relations, not as a goal in itself.”

But while the clock is ticking, there is no particular urgency. Nobody now remembers that Bordiau missed his deadline in 1880, that it took another 25 years to complete the arcade, and nobody knew exactly how it would look until shortly beforehand.

We don’t know what the Cinquantenaire will look like in 2030 and nobody will remember that the heads of its organising committee were sacked in the summer of 2023. As an organiser told Le Soir, off the record, 2030 is more of an operational deadline to finalise the shape of the project: “It should be launched in 2030. It’s very good to have this date as a target but we need to be thinking in terms of 2100.”

Onwards and upwards. The covering for the tunnels, dreamed of by locals since the day they were completed, may or may not be realised, but the festivities under the Cinquantenaire 2030 banner start already this year.

From October, the Art & History Museum in the park will host an exhibition in honour of Austrian architect Josef Hoffmann. He created the future himself once, in 1907, when he designed the Stoclet Palace, two roundabouts down from the Cinquantenaire along Leopold II’s ceremonial route to Tervuren. A vast building 20 years ahead of its time and which defies categorisation, the Stoclet Palace dates from a time when Brussels looked towards Vienna for inspiration, instead of Paris or New York.

UNESCO World Heritage-listed, barely anyone has ever been inside the Stoclet Palace as the family that still owns it refuses entry. Perhaps the finest feather in any 2030 organiser’s cap, and the best deadline of all, would be securing public access to that sphinx by the summer of 2030.