In Europe as elsewhere, the realization of bold ideas requires long, strenuous, continuous efforts by people who never lose faith. A popular senior Brazilian politician who campaigns tirelessly, sometimes beyond his own limits, for the introduction of an unconditional basic income, provides a role model for all those who struggle for a more just society around the world.

Philosopher Philippe Van Parijs reflects on current debates in Brussels, Belgium and Europe

A very unusual trajectory

It should have been his congress, the culmination of the worldwide impact of his relentless struggle. But on the first day of the 24th congress of the Basic Income Earth Network (BIEN), held in Maricá and Niterói (close to Rio de Janeiro) on 25-29 August 2025, he had to be hospitalised and resign himself to online participation from his hospital bed.

The 84 years old reluctant patient is an exceptional person. His name is Eduardo Matarazzo Suplicy. Through his mother, he is one of the many descendants of Count Francesco Matarazzo, an Italian immigrant and entrepreneur who contributed more than anyone to making São Paulo Brazil’s industrial capital.

With a doctorate in economics from an American university, he became a professor at Brazil’s top business school, the Fundação Getúlio Vargas in São Paulo. None of this could have made one expect that in 1980, together with a fierce labour leader nicknamed Lula, he co-founded Brazil's Workers Party, the PT, nor that, in 1991, he became (and remained for 24 years) the party’s first federal senator.

Eduard Suplicy (future senator), Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (future president) and Fernando Henrique Cardoso (future president) in 1978

I first met him in Rio de Janeiro in July 1994 and invited him to attend, in September of the same year, the London congress of the Basic Income European Network, a network founded in Louvain-la-Neuve in 1986. He soon became convinced that an unconditional basic income was the way to go, in Brazil no less than in Europe. In October 1996, I was back in Brazil and we went together to Brasilia to meet President Fernando-Henrique Cardoso, his former colleague at the Fundação Getúlio Vargas.

On the way towards a universal basic income

At the time, several municipalities, most notably Campinas and the federal district of Brasilia, had introduced a Bolsa Escola, a modest means-tested guaranteed minimum income scheme coupled with a condition of school attendance. But these were relatively rich municipalities. To be feasible elsewhere, such a scheme required federal funding.

Cardoso was receptive to our arguments: the deployment of such a scheme in the whole country would be (and could be politically sold as) an investment in Brazil’s human capital and would help slow down migration from the rural North to the favelas of overcrowded metropolises. In 2001, he introduced a nation-wide Bolsa-Alimentação for poor families with small children entirely funded at the federal level.

This was a major step forward, but Suplicy was convinced that it was desirable and possible to go much further. In 2003, during the first year of Lula’s presidency, he managed to get both chambers of Brazil’s parliament to approve a law that created a “citizenship basic income” for all Brazilians, to be introduced gradually, starting with the neediest households. The law was signed by President Lula during a ceremony held at Brasilia’s presidential palace on 8 January 2004.

The “gradual implementation” took mainly the form of a general social assistance scheme labelled Bolsa Familia, the key tool for realizing Lula’s electoral promise of Fome Zero (zero hunger). The provisional measure that created it in October 2003 was converted into law on 9 January 2004, one day after the signing of the basic income law.

Like the Bolsa Escola, the Bolsa Familia is conditional upon school attendance for families with school-age children. Both the level of the benefit and the share of the Brazilian population receiving it have expanded considerably since then, including, under the temporarily modified name Auxilio Brazil, during Bolsonaro’s presidency.

Exploring the next steps

The Bolsa Familia has inspired many other social assistance programmes elsewhere in the world. It has uncontroversially contributed to reducing extreme poverty in Brazil and to lowering its level of inequality, one of the highest in the world. But it is not sufficient to satisfy Suplicy’s more radical ambition.

With his team, he is now studying the possibility of funding a nation-wide universal basic income by re-introducing the tax on all financial transactions that was in place in Brazil between 1997 and 2007. The tax had been introduced under Cardoso but was terminated under Lula because it could not get the two-thirds majority in the senate that was required to extend it. With a rate of 0.38%, the revenues it generated were of the same order as those of Brazil’s income tax.

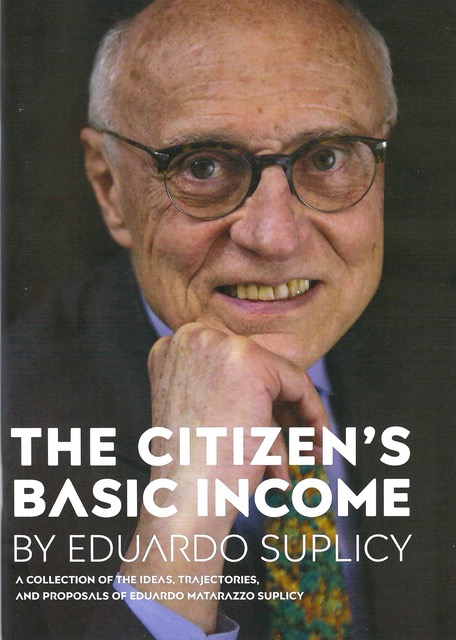

Eduardo Suplicy’s latest book (São Paulo, August 2025)

Suplicy’s team is also exploring the possibility of introducing a state-level universal child benefit in the state of São Paulo (where he is now a member of the state assembly), funded by an increase in inheritance tax. Inheritance tax is a state-level competence, with the Brazilian constitution imposing a maximum rate of 8%. Some states adopted a progressive tax profile rising from 2 to 8%. São Paulo has a uniform rate of 4%.

Suplicy’s plea for an unconditional basic income also inspired two widely discussed local schemes closer to it than the Bolsa Familia: an individual uniform benefit funded by royalties on the extraction of oil and paid in a local currency (the mumbuca and the arariboia, respectively) to a large proportion of the residents of the cities of Maricá and Niterói.

This twofold initiative, along with the hospitality offered by the universities of Vassouras (in Maricá) and Fluminense (in Niterói), explains the choice of venue for this 24th BIEN congress. It is also one reason why this congress would not have been held there had it not been for Eduardo Suplicy’s campaigning. But it is not the only reason.

A realistic utopia for the whole world

Soon after he started attending the congresses of BIEN, at the time still the Basic Income European Network, Suplicy started lobbying for the network to become global. At the time, I was BIEN’s secretary and found it hard enough to keep it going at the European level (this was still the pre-internet era). Above all, I thought that an unconditional basic income only made real sense in the context of countries with developed welfare states that had shown their limits.

However, in January 2004, I attended in Brasilia the ceremony during which Lula officially signed Suplicy’ basic income law. I returned home converted. In September 2004, at its 10th congress held in Barcelona, the Basic Income European Network became the Basic Income Earth Network.

Eduardo Suplicy offers an extraordinary example of persuasive power and persevering militancy in the service of a “utopian” proposal intended to make our societies more just. For this reason, the University of Louvain awarded him an honorary degree (at the same time as the founder of Wikipedia, Jimmy Wales, and the architect Paola Viganò) in February 2016, as part of the celebration of the 500th anniversary of the publication (in Louvain) of Thomas More’s Utopia.

However, the basic income network itself can also be regarded as a model of perseverance. When it was created in 1986, hardly anyone had heard of the proposal for an unconditional basic income, and if you happened to mention it, people thought you were joking — or crazy. Today, the idea has spread around the world. BIEN’s latest annual congresses were held in Brisbane, Seoul and Bath, the next ones will be held in Philadelphia, Wroclav and Taipeh.

In the darkest times

What about Europe? Twenty years ago, a South-African colleague told me: “Philippe, you are as arrogant as Karl Marx. He thought that socialism could only be introduced in industrialized Western Europe. Instead, the revolution happened in agrarian Russia and China.

Similarly, it is in countries such as South Africa that the unconditional basic income will be introduced first.” Perhaps. The war in Ukraine and the catastrophic increase in military expenditure it is causing are certainly not good news for Europe’s chances.

But in Europe as in Brazil, for a universal basic income as for universal suffrage or the abolition of slavery, it is in the darkest times that perseverance is most valuable. As I was checking in at Rio’s airport after the end of the BIEN congress, Eduardo Suplicy called me : “I am better now. Ready to keep fighting until basic income is introduced in Brazil … and in the whole world!”