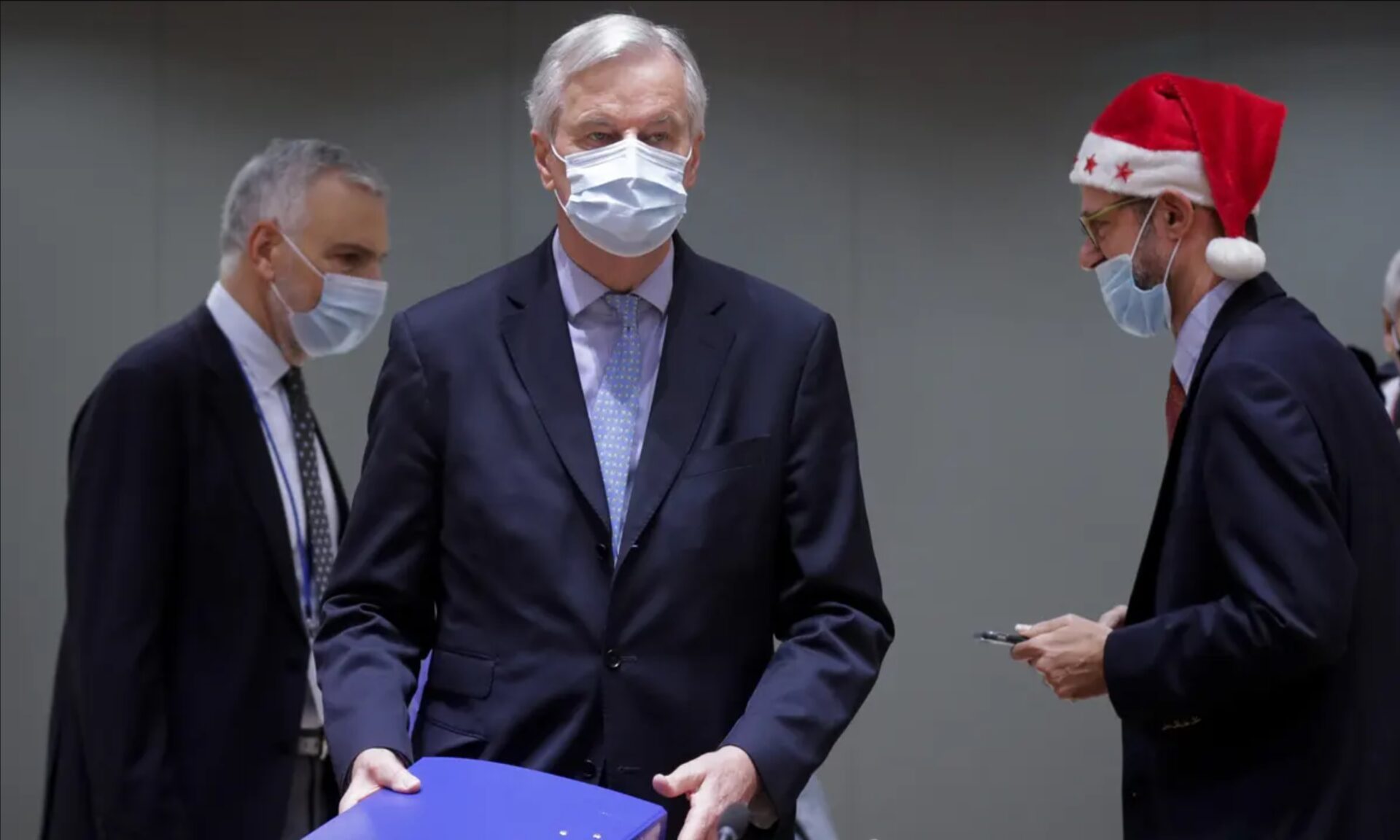

“On 24 December a few were still in the office close to midnight and some continued working throughout that night from home. Barnier spent the evening of Christmas Eve by himself in his rental place in Brussels instead of with his family in France and prepared what to say at an extraordinary COREPER meeting with the 27 ambassadors at 11 am on Christmas Day."

"It was a fitting end to three-and-a-half years of extraordinary efforts by EU officials to get Brexit done. Cancelling holidays and missing concerts, weddings and birthday parties since 2017 preceded the gloomy 2020 Christmas in the Berlaymont, at the service of a Brexit project which none of them considered to be beneficial, neither for the UK nor for the EU.”

This was the final effort of the EU’s Brexit team led by Michel Barnier, as described in Inside the Deal. How the EU got Brexit done, a thrilling account recently published by Stefaan De Rynck, one of its senior members.

It all started on 23 June 2016, when 37% of the British electorate — 52% of those who voted — replied no to the question “Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union?”.

To most people in Brussels this came as a surprise, and to many as a disaster. For some of them, it meant above all the stupid sacrificing of the economic benefits of a larger market, the painful loss of one of the net contributors to the EU budget, a dramatic shrinking of the demographic, economic and diplomatic weight of the Union, or a sudden halt to what they believed to be the irreversible march of European integration through both deepening and expanding.

For others — myself included — it meant first and foremost a sad regression from regarding the Brits as some of “us” to regarding them as just a “them”, from joint deliberation aiming at fairness and the common good to inimical bargaining in the service of our respective separate interests.

After the first shock, it quickly became clear that a complex exit deal would need to be struck, and that a bad deal could make the disaster even worse. By recreating a physical border between North and South, Brexit could re-ignite civil violence in Northern Ireland. By highlighting the very different extents to which member states were affected by the UK’s departure, it could unleash fierce public tensions between the remaining member states. By allowing the UK to keep some access to the single market while evading its rules, it could trap the EU in the “Thatcherian” dream of downward tax, social and regulatory competition. And by allowing the UK to cherry-pick the elements of the European construction that were to its advantage, it would encourage more member states to secede in turn, thereby precipitating the disintegration of the Union.

The EU saw the dangers and acted promptly. On 27 July 2016, just over a month after the referendum and two weeks after Theresa May replaced David Cameron as the UK’s Prime Minister, former EU commissioner Michel Barnier was appointed EU chief negotiator. He immediately formed a small task force, started mobilizing expertise from all corners of the European Commission and undertook to meet systematically the governments of the 27 other member states.

The UK was informed that no negotiation would start before it had officially requested the activation of Article 50 of the Treaty of European Union, thereby triggering an obligation to reach a withdrawal agreement within two years. It was also informed that the discussion of the future relations between the EU and the UK could only seriously get off the ground once the withdrawal agreement had been signed.

Article 50 was activated by Theresa May on 29 March 2017. The clock started ticking, but progress was not smooth. On 8 June 2017, Theresa May lost her absolute majority at the national election she had called. Her attempts to strike a mutually acceptable deal led the following year to the resignation of two successive Brexit ministers, David Davies and Dominic Raab, and of one foreign secretary, Boris Johnson.

The draft deal that emerged from the negotiations was rejected three times by the British Parliament between January and March 2019, despite extra assurances by the EU. In order to avoid a no-deal departure, the Article 50 deadline was extended to from 29 March to 31 October 2019, thereby forcing the UK to take part in the May 2019 elections for the Parliament of the Union its government was so desperate to quit.

This was the memorable period in which the European public discovered with a mixture of amusement, horror and admiration that the people standing in the middle alley of the House of Commons were not subordinate staff but MPs who had arrived too late to get a seat, that the Speaker of the House was expected to act as both a moderator and an entertainer, and that MPs could not vote by pushing a button as their colleagues can do all over the world but had to get up and gather in an “Aye lobby” and a “No lobby” in order to be counted.

On 24 July 2019, Boris Johnson replaced Theresa May as British Prime Minister. He called another national election for 12 December. To the paradoxical relief of many in Brussels, the campaign he conducted under the motto “Get Brexit done” gave him a comfortable majority.

A revised withdrawal agreement was soon approved by both the British and the European Parliament. On 31 January 2020, the UK ceased to be a member state of the EU, while retaining most of its obligations and rights until the end of a transitional period due to end on 31 December 2020.

Pressed by the deadline, discussions could then officially start on the “future relations”. They led to the “Trade and Cooperation Agreement”, approved by PM Johnson and Commission President Ursula von der Leyen on 24 December and given a final touch on Christmas eve 2020, as narrated in the quote above.

In his book, Stefaan De Rynck narrates how Barnier’s team had to navigate these many false starts, mishaps and upheavals. It was a thankless, arduous, stressful job, but also an important and even gratifying one. De Rynck does not hide the pride, indeed even sometimes the joy, of being part of a strong, cohesive team, led by an empathic and astute politician assisted by competent and committed top officials.

Against all odds, they managed to maintain solidarity between the 27 member states, even amidst tense negotiations on issues some of which affected directly just one member state — Northern Ireland — or just a few — North Sea fishing rights.

Their brief, fundamentally, was to ensure that the Brits, notwithstanding the naïve or unscrupulous promises made to them by some of their politicians, could not have their cake and eat it. Did they succeed? Some recent statistics suggest that they did. Successive YouGov surveys show that the percentage of the British electorate that considers Brexit to be a wrong decision has steadily risen to 56%, while the proportion of the electorate that considers it to be a good decision has dropped to 32%.

WhatUKThinks’s data indicate that in the event of a new referendum, 58.5% would vote to rejoin the EU and only 41.5% to remain out of it. And the bi-annual European Social Survey showed that support for leaving the European Union dropped significantly in all 27 member states between 2016 and 2022.

Total disaster averted? If so, mission accomplished, Mr Barnier.