History does not repeat itself. But there is nothing else we can learn from. The names given to two parks in Brussels’ European Quarter remind us of two ways in which a war can end, 2000 and 200 years ago but also today. One of them enjoys the Pope’s preference. Mine too.

Philosopher Philippe Van Parijs reflects on current debates in Brussels, Belgium and Europe

Louise and Marguerite

In the shadow of the European Commission’s headquarters, lies a string of small parks: Square Marie-Louise, Avenue Palmerston, Square Ambiorix, Square Marguerite. Designed in the 1870s and bordered by some of Brussels’ most famous Art Nouveau houses, they aimed to attract the bourgeoisie of the capital of the Kingdom of Belgium, proud of its newly gained independence and of its rapid industrial development.

The names given to these small parks were intended to reflect this pride. Square Marie-Louise refers to Belgium’s first queen, Louise-Marie d’Orléans (1812-1850), wife of Leopold I. Square Marguerite refers to Brussels-born Marguerite of Austria (1480-1530), who brought up the future Emperor Charles V and governed the Low Countries on his behalf from 1515 to 1530: a glorious period in the history of Brussels, when the gigantic Habsburg Empire was ruled from Brussels’ Coudenberg Palace.

Ambiorix and Palmerston

The third historical moment being celebrated goes back to Caesar’s conquest of this part of the world. His De Bello Gallico contains a sentence that has been repeatedly taught with relish to Belgian pupils ever since Belgium was born: Horum omnium fortissimi sunt Belgae. Of all Gauls, the Belgians are the most courageous. And the most courageous among the most courageous were the Eburones. Their resistance was so fierce that Caesar felt forced to exterminate them: a genuine genocide avant la lettre. Ambiorix, the Eburones’ leader, is believed to have escaped Caesar’s wrath by crossing the Rhine. Two millennia later, Square Ambiorix ensures that he is not entirely forgotten.

Even though Marie-Louise was born in Palermo, even though Marguerite was the daughter of an Austrian emperor, even though Ambiorix died somewhere on what is now German territory, all three can be regarded as locals. But what about Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, British Prime Minister from 1859 to 1865, after whom the fourth park is named? A brief glance at the agitated birth of independent Belgium sheds light on his mysterious presence among this glorious “Belgian” company.

The Dutch-Belgian war

The 1830 “Belgian revolution” against the Dutch King William I triggered a war between Belgium and the Netherlands. The Belgians were supported by the French, who sent an army of over 50.000 men, headed by France’s future prime minister Etienne Maurice Gérard, to help push back the Dutch troops in 1831. And several of the Belgian leaders, including Charles Rogier and Charles de Brouckère, were quite sympathetic to the idea that Belgium should become part of the French Republic. This was not to the liking of the United Kingdom and its newly appointed foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston, however.

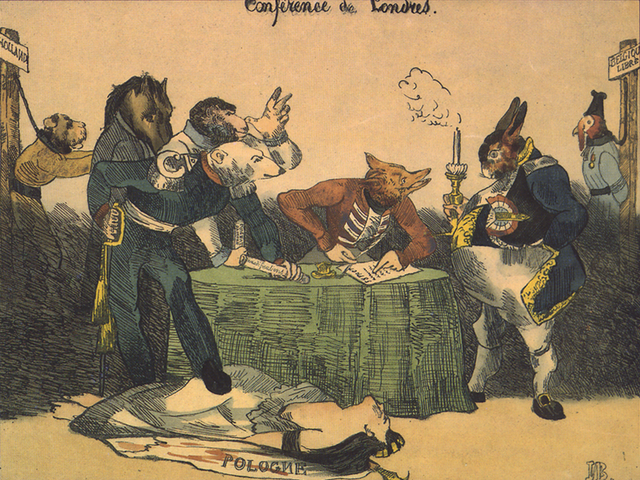

In 1831, Palmerston convened a conference in London at the end of 1830 and managed to get Belgium, together with the great powers of the time — Prussia, Russia, Austria, France, in addition to the UK —, to sign the following year a treaty known as the Treaty of the XXVII Articles (15 November 1831). The proposed agreement granted Belgium independence, providing it renounced its claim to half the province of Limburg and half of Luxemburg. The King of the Netherlands, however, refused to ratify it.

Hostilities continued until 1839, when Palmerston convened another meeting in London which produced another treaty (the Treaty of the XXIV Articles of 19 April 1839), with essentially the same deal. This time, both parties complied with it. Belgium was definitively granted national sovereignty, but at the expense of its territorial integrity. Part of Limburg, including the city of Maastricht, was retroceded to the Dutch King - and the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg, with the Dutch King as its Grand Duke, was carved out of the province of Luxemburg.

Two ways of ending a war

Lying adjacent to one another in Brussels’ European Quarter, Ambiorix and Palmerston epitomize two ways in which a bloody conflict can end: a refusal to submit, which ends up in the suicide of a people, and a negotiation that achieves peace through both parties reluctantly accepting concessions they regard as unjust.

Did Ambiorix ever ask himself whether he should negotiate rather than resist, in order to save his people from extermination? No one will ever know. Do President Zelensky and the Hamas leaders ever ask themselves analogous questions? Have they ever asked themselves whether the responsible thing for them to do would be to renounce their most ambitious territorial claims, a return to the pre-2014 borders, Crimea included, “Free Palestine from the river to the sea”? Did they ever consider doing something similar to what the Belgians did in 1839 and the Irish in 1921: agreeing to renounce territorial integrity for the sake of securing their national sovereignty?

Pope Francis and the white flag of negotiation

Whether or not they did, there is no doubt that pope Francis believes they should do. In the interview broadcast on 20 March by the Italian-medium Swiss TV channel, he said: "Negotiation is never surrender. It is the courage not to lead the country to suicide. I believe that the strong one is the one who sees the situation, thinks of the people and has the courage of the white flag, the courage to negotiate. And today you can negotiate with the help of the international powers… Today, for example, with the war in Ukraine, there are many who want to be mediators, Turkey for example."

Could Erdogan or anyone else play for the Russo-Ukrainian or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict the role that Palmerston played for the Dutch-Belgian conflict? Palmerston’s government had a strong motivation to intervene. If it did not, there was a good chance that France would swallow Belgium. Moreover, the power of the British army was more than sufficient for the mediator to be, if needed, a credible enforcer.

Is any of the “international powers” invoked by the pope both sufficiently motivated and sufficiently powerful? If not, is the Ambiorix scenario unavoidable, with Putin and Netanyahu in Caesar’s role? Or is there hope that, at some point, on each side of the two conflicts, “the courage of the white flag” will put an end to the local butcheries and to the even more disastrous global collateral damages?