At the end of February, rockets rained down on Ukraine’s capital city of Kyiv. Russian forces launched attacks into the north of the city, pushing into the Troieshchyna and Obolon districts. Enemy saboteurs marked buildings for destruction in the dead of the night. Strict curfews served as a backdrop for the hunt of Russian reconnaissance parties.

In Kyiv, the situation was dire. Locals feared that they would soon lose their homes, or worse, their country.

Just two months later, however, the city looks remarkably different, and so do the city's locals. Young people gather for coffee in colourfully decorated cafés in Kyiv’s chic Zoloti Vorota neighbourhood. Far from rationing, up-market supermarket chain Silpo sells imported avocados and sushi sets to office workers from some of the city’s many IT companies.

Locals return to Kyiv

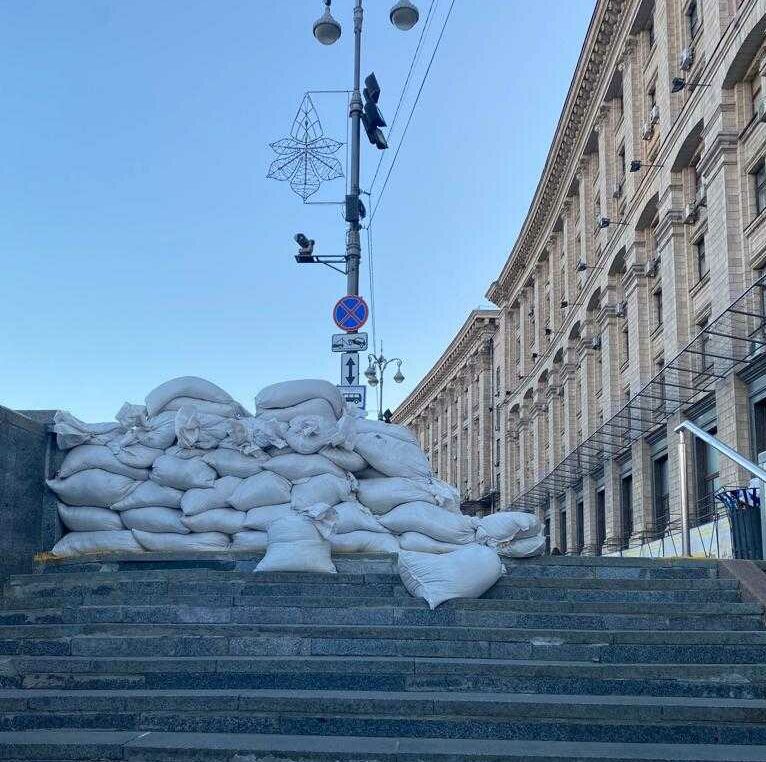

The war has undeniably left its mark on the city. Sandbags pile high in front of key government buildings, the names of certain streets remain taped over, menacing Czech Hedgehog tank traps line some of the city’s busy streets, and some of the city’s northern districts are still littered with mines left by Russian occupying forces.

Sandbags piled up outside of a metro station entrance on Kyiv's iconic Khreshchatyk street. Credit: Vladyslava Belau

While the war rages fiercely in the east of the country, Kyiv is relatively stable. Ukrainians are returning to the city en masse. According to Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko, the population of Kyiv has returned to around 71% of its pre-war levels.

While the city is slowly recovering, the mayor has warned that it is still not entirely safe to return. Kyiv is just 150 kilometres away from the border with Russian puppet state Belarus and the risk of new provocations and rocket attacks is high.

At the Davos conference on 24 May, Klitschko warned that the Kyiv administration could not give “guarantees of safety for every citizen because every second, every minute, a Russian rocket can land in an apartment building. That’s why we say to everyone, if you decide to come back, it is at your own risk.”

Despite the Mayor’s warning, Kyiv’s young and increasingly international population are beginning to return to their everyday lives. Vladyslava Belau, originally from Kherson, a city under occupation by Russian forces since March, made the decision to return to Kyiv on 13 May.

Home

One day after the outbreak of the war, Belau fled Kyiv by train as thousands attempted to flee the capital. “It was a total disaster. It was the most terrifying thing during this war,” she told the Brussels Times. Like many other Ukrainians, she settled with a friend’s family in the western Ukrainian city of Lviv.

The population of Lviv more than tripled since the outbreak of the war. Belau stated that she did not want to flee abroad because the experience would be too difficult. “It’s safer, but emotionally, I think, it’s worse.”

Belau had split much of her childhood between three Ukrainian cities, Kherson, Kharkiv, and Kyiv. At that time, Kharkiv was being mercilessly bombed by Russian forces and Kherson was under Russian control. After spending around three months in the west of Ukraine, Belau became increasingly restless.

“Russia had taken away from me all my homes, and the moment when Bucha, Irpin, and this stuff was liberated by the Ukrainian army, I thought like- so now I have one home, I should live there,” Belau said.

Some street names were deliberately covered up by Ukrainian forces to disorientate potential Russian invaders. Credit: Vladyslava Belau

The decision to return, of course, was not without its worries. At the end of April, a rocket attack against the capital had killed a journalist. “It’s really hard to make a decision to go back to a place where you once felt unsafe,” she said.

Her return to the capital, she rationalised, would be like an “expedition.” Speaking to the Brussels Times at that time, Belau had been in Kyiv for a week, and said she had definitely made the right decision.

“The first day when I moved back, it was such a lot of dopamine. I couldn’t sleep because it felt like you’re falling in love with someone… and for me that’s a sign that I can feel safe.”

Kyiv learns to live again

Belau says that life in Kyiv is now comparable to the situation that existed during the Covid-19 lockdowns in Ukraine. The streets are noticeably quieter, but people “really want to live their lives.”

“You’re riding your electric bikes, riding with Airpods in your ear, feeling happy that you are living in such a city of Kyiv, but you are riding through these sandbags. We sit in cafes with hipsters, we drink our cappuccinos with coconut milk and so on, but military guys are sitting with us. It’s surreal,” she explained.

Related News

- 'It was mayhem': A Belgian’s escape from Ukraine

- Ukraine and Moldova given official EU candidate status

- Belgium to reopen embassy in Kyiv

Belau acknowledges that this sounds weird, especially for Belgian readers. War rages around the country, but a large contingent of Kyiv’s population continue with their social lives, enjoying the city’s many popular restaurants and cafés.

One could almost believe things had completely returned to normal, if not for some strange new realities that Kyivans have become accustomed to. “You’re not allowed to go outside from 11 pm. But I know some Ukrainian don’t really care about this rule sometimes,” she explains.

Belau saw her friends in Kyiv again after nearly three months of absence. Credit: Vladyslava Belau

As a result of this strange new reality, young sociable Ukrainian young people now plan their social lives around these new military curfews, sleeping at each other's houses, or even partying through the night in secret bars until the curfew lifts in the morning.

Locals talk of a certain secretive and illegal underground bar which has become a hive for journalists and off-duty soldiers to drink and gather, and even shelter from rocket attacks. “Co-working with alcohol”, Belau calls it.

“At any moment, rockets, missile strikes can kill you. But you’re just still living your life. You’re planning meetings with your friends, you even drink alcohol on the street, no one cares about it. I don’t know what changed. Maybe people have changed,” she explained.

Not quite normal

Other issues are more serious. Petrol and other fuels are in short supply. The immediate impact is that the streets are increasingly devoid of cars. Petrol is increasingly hard to find because it is being heavily used by the army, which also leads Russia to target Ukrainian fuel depots to frustrate supply.

As such, there are few journeys being taken by car and taxi drivers are struggling to make a living. A record number of locals are buying electric scooters and bicycles to help them get around.

Kyiv's metro system continues to work as normal. Credit: Vladyslava Belau

“I’ve seen long, long queues for petrol. It leads to different humanitarian infrastructure problems. People living in destroyed houses outside the capital, they need humanitarian aid. Because of a lack of petrol, people cannot drive to get this humanitarian aid,” Belau explained.

[custom-related-posts title="Related Posts" none_text="None found" order_by="title" order="ASC"]

There is also a growing sense of apathy towards rocket early-warning systems. People are increasingly ignoring rocket warning and sirens as they have grown so accustomed to the threat of bombardment. “I just keep sitting at the coffee table, drinking beer, doing my work. I don’t know. It’s like no one really cares anymore.”

People may care again soon. Rocket attacks could increase in intensity at any time. There is even the threat that Belarus may join the conflict and launch attacks across the borders with Ukraine. When asked whether she would consider leaving again, Belau faltered.

“Yes I think so… I don’t know. Maybe not. I regret that I left Kyiv sometimes. I think, this time, I would stay because I really believe in our army. In Kyiv we were once afraid, but now I’m not scared to even go to Kharkiv,” Belau concluded. “I guess you build up a tolerance.”