All countries of the WHO European Region – encompassing 53 Member States across Europe and Central Asia - currently face severe challenges related to the health and care workforce (HCWF), according to a new report published on Wednesday by WHO/Europe.

The report was released at the 72nd session of the WHO Regional Committee for Europe, which took place this week in Tel Aviv, Israel, the first in-person Regional Committee meeting in three years.

It offers a picture of the HCWF in the region based on available data provided by countries in 2022. In many cases, these data are incomplete. The report focuses on six groups of health care workers for whom data are available - medical doctors, nurses, midwives, dentists, pharmacists and physiotherapists. No data on informal health workers are included.

An ageing workforce is the most important among the challenges. 13 of the 44 countries that have reported data on this issue have a workforce in which 40% of medical doctors are already aged 55 years or older. An ageing health and care workforce was a serious problem before the COVID-19 pandemic, but even more so now, with severe burnout and demographic factors contributing to an ever-shrinking labour force.

Adequately replacing retiring doctors – and other health and care workers – will be a significant policy concern for governments and health authorities in the coming years. WHO/Europe is urging countries to act now to train, recruit, and retain the next generation of health workers.

Another key finding is the poor mental health of the HCWF. Long working hours, inadequate professional support, serious staff shortages as well as high COVID-19 infection and death rates among frontline workers—especially during the pandemic’s early stages—have left a mark on the European Region’s health workforce.

Health worker absences in the European Region increased by 62% amid the first wave of the pandemic in March 2020, and mental health issues were reported in almost all countries in the Region. In some countries, over 80% of nurses reported some form of psychological distress caused by the pandemic and a majority of them had declared their intention to quit their jobs.

Mixed picture across the region

While the 53 countries of the European Region have on average the highest availability of doctors, nurses and midwives compared to other regions, Europe and Central Asia still face substantial shortages and gaps, with significant sub-regional variations.

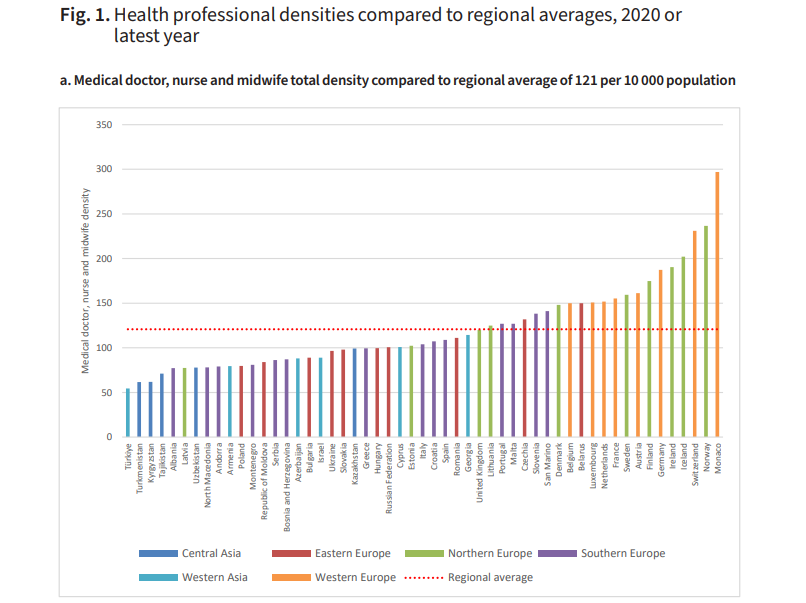

The regional average of the aggregate doctor-, nurse- and midwife-to-population density is 121 per 10,000 people but varies five-fold between countries. It ranges from 54.3 per 10,000 people in Turkey to over 200 per 10,000 people in Iceland, Norway, Monaco, and Switzerland. At sub-regional level, central and western Asia have the lowest densities and northern and western Europe the highest.

Credit: WHO/Europe

Based on the latest data available for 2022, the WHO European Region has on average 80 nurses per 10,000 people, 37 doctors per 10,000 people, 8 physiotherapists per 10,000 people, 6.9 pharmacists per 10,000 people, 6.7 dentists per 10,000 people, and 4.1 midwives per 10,000 people.

A breakdown by health care worker category shows significant differences in density by country - what should be the right balance?

“There is no ‘right’ or recommended balance or skill mix across professions,” Dr Tomas Zapata, Regional Adviser, Health Workforce and Service Delivery at WHO/Europe, and lead editor of the report, told The Brussels Times.

“However, the regional average ratio of nurses and midwifes to doctors is about 2.27. This means that most countries actually have more nurses than doctors to provide health services. In for example Greece, with the highest medical doctor density, the ratio is the inverse with nearly twice as many doctors as nurses.”

He added that nurses play an important role in providing promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative care. That’s why WHO/Europe recommends that nurses play a more active role in the provision of care. Also, multidisciplinary teams (teams made up of different specialists such as doctors, nurses, psychologists, social workers, midwives, physiotherapists) are more effective in primary care services and are able to really provide comprehensive care to patients.

Ten actions to strengthen HCWF

In WHO’s 2016 global strategy for human resources for health, the threshold for aggregate health worker density was set at 44.5 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000 people. All countries in the European Region are therefore currently above the threshold, but this does not mean they can be complacent, according to WHO.

“Personnel shortages, insufficient recruitment and retention, migration of qualified workers, unattractive working conditions, and poor access to continuing professional development opportunities are blighting health systems,” said Dr Hans Henri P. Kluge, WHO Regional Director for Europe.

“These are compounded by inadequate data and limited analytical capacity, poor governance and management, lack of strategic planning and insufficient investment in developing the workforce. Furthermore, WHO estimates that roughly 50,000 health and care workers may have lost their lives due to COVID-19 in Europe alone.”

“All these threats represent a ticking timebomb which, if not addressed, are likely to lead to poor health outcomes across the board, long waiting times for treatment, many preventable deaths, and potentially even health system collapse,” warned Dr Kluge.

“The time to act on health and care workforce shortages is now. Moreover, countries are responding to the challenges at a time of acute economic crisis, which demands effective, innovative and smart approaches.”

WHO/Europe is urging Member States to waste no time by implementing a practical ten-point plan to address existing gaps and strengthen the health and care workforce, even in those countries with above-average HCWF densities at the present time.

In his concluding speech at the meeting, Dr Kluge said that the plan includes making health sector jobs more attractive by increasing salaries, developing future healthcare leaders, supporting professional development and mental health, improving data-gathering, and making better use of digital tools.

The latter is one of the flagship pillars of WHO/Europe's Programme of Work, whose action plan was formally adopted by the Member States at the meeting.

Tackling the health and care workforce crisis is absolutely critical to successfully navigate the Dual Track in what he called the New Normal. “In a world of ever-rising health crises, at a time of economic turmoil, we must accept and work within the reality of a New Normal – requiring a Dual Track approach to health.”

“This means, on the one hand, we must significantly invest in preparedness for mounting and often overlapping emergencies. On the other hand, we must ensure that we maintain and strengthen day-to-day, essential health services all the more. Equal emphasis and priority for both. A Dual Track approach for the New Normal. And this is really a lesson learnt from COVID-19.”

M. Apelblat

The Brussels Times