Feared and reviled down the centuries, freemasons are still treated with suspicion.

Seven starving Belgian political prisoners sat around a table in barrack Number 6, a wooden hut in the Nazi concentration camp at Esterwegen in northwest Germany on a freezing day in November 1943. A Catholic priest, also an inmate at the camp, kept a lookout while the men inside held the inaugural meeting of a masonic lodge. They named the lodge Liberté Chérie or Darling Freedom.

As the oldest freemason present, Paul Hanson, a 54-year-old judge from Liege took on the role of leader, or Worshipful Master of Liberté Chérie. The others were all professional types too: lawyers, teachers, journalists, pharmacists and doctors. Liberté Chérie lodge only existed for a few months but met several times to discuss topics such as the position of women and how to rebuild Belgium after the war.

The story of Liberté Chérie is retold each year at a memorial gathering of Belgian freemasons in Breendonk Fort, near Antwerp. Like Esterwegen, Breendonk was also used by the Nazis to lock up Belgian political prisoners. The fort is a museum now. For the past 33 years, Belgian freemasons have gathered at this grim site to remember not just their brothers, but all the victims of the Nazis.

It’s a sunny morning in May and a crowd of around 150 men and women, mostly middle-aged or retired - but also surprisingly a group of bikers -are walking solemnly in three parallel lines through the eery, windowless concrete passageways of Breendonk Fort, guided by ushers wearing white gloves, some carrying musical instruments. No one speaks.

At various points along the two-hour guided tour of the fort’s dungeons, dorms, exercise yards and gallows, the ushers would stop and break into nostalgic song. Lili Marleen, Auld Lang Syne with lyrics from the trenches of the First World War. Imagine by John Lennon. A lot of effort has been made to set the mood.

Fort Breendonk

“We went to Breendonk to remember. Not just the freemasons but all people persecuted by the Nazis, all victims of totalitarianism. The message is very simple: never forget,” says Dr Alain Cornet, the Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Belgium masonic lodge, and Belgium’s most senior freemason.

Threat levels

Before taking on the three-year elected post of Grand Master Dr Cornet worked as a urologist in his native Flanders. He spoke to The Brussels Times in a personal, not official capacity, in his office above the Belgian Museum of Freemasonry near Place de Brouckère in downtown Brussels.

Since its inception in the early 18th century, modern freemasonry has acquired powerful enemies. The Nazis shut down Masonic lodges in Germany, as well as in the countries they occupied during the second world war. Freemasonry all but disappeared in Russia in the 19th century and only resurfaced again after the fall of communism in 1991.

The Roman Catholic church sees freemasonry as a threat. Popes from the 1730s through to the 21st century forbid Catholics from joining the movement.

“Freemasons have always promoted free thought, self-determination. Churches are very hierarchical: you don’t ask questions and you obey orders. Freemasons ask questions and they do not obey orders. The church doesn’t like that,” says Dr Cornet, describing it as a clash between “dogma and adogma”.

But in the mid 19th century the threat from freemasonry to the Catholic church started to resemble a battle for the souls of future generations. Freemasons were among the most prominent advocates for the creation of non-religious, or Laic public education.

Dr Alain Cornet, the Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Belgium masonic lodge. Credit: Paul Meller

“Education is where freemasonry has left its most important mark on Brussels,” says Roel Jacobs, a freemason and author of Bruxelles-Pentagone, a book about the architecture and history of the city. “Brussels had a secular public school system before Paris, and it’s in large part thanks to the efforts of freemasons.”

The Universite Libre de Bruxelles (ULB) was founded by Pierre-Theodore Verhaegen, a prominent freemason, in 1834, breaking from the Catholic University of Leuven’s (UCL) dominance of higher education in Belgium.

Thirty years later, Isabelle Gatti de Gamond, a Belgian educationalist and feminist created the first secular secondary school system for girls. She became a freemason in her autumn years, at the turn of the century. And around the same time, celebrated Belgian architects including Victor Horta and Henri Jacobs, also freemasons, were building secular kindergartens and primary schools in Brussels.

The liberalising zeal of Belgium’s freemasons extended beyond education and continued throughout the 20th century and into the 21st. Women were finally allowed to vote in Belgian national elections in 1949, thanks partly to freemasons who stood up to Catholic pressure to suppress women’s voting rights.

Inside the Brussels temple

Roger Lallemand, a prominent socialist politician and lifelong freemason led the drive to legalise abortion in 1990. In 2002 Belgium was one of the first countries in the world to legalize euthanasia, and again, freemasons were on the ethical front line facing down the Catholic church in that debate.

As with Christianity, freemasonry also had a schism. In the late 19th century, freemasons in France, Belgium and other predominantly Catholic countries broke off from the lodges in Britain, by declaring that freemasons no longer had to believe in the existence of a Supreme Being or revealed God, or grand architect of the universe, as freemasons put it.

Two distinct versions of freemasonry emerged from this split. Most lodges in countries including the UK, Sweden and, significantly, Germany, held on to the theology, while most lodges in Belgium, France and other Catholic countries turned their focus from religious-like beliefs to progressive values.

Fear and loathing

Despite its role in spreading progressive values in Belgium, and the fact that it was despised by totalitarian dictators from both the left and the right, and shunned by an ultra-conservative Catholic church, freemasonry still gets a bad press.

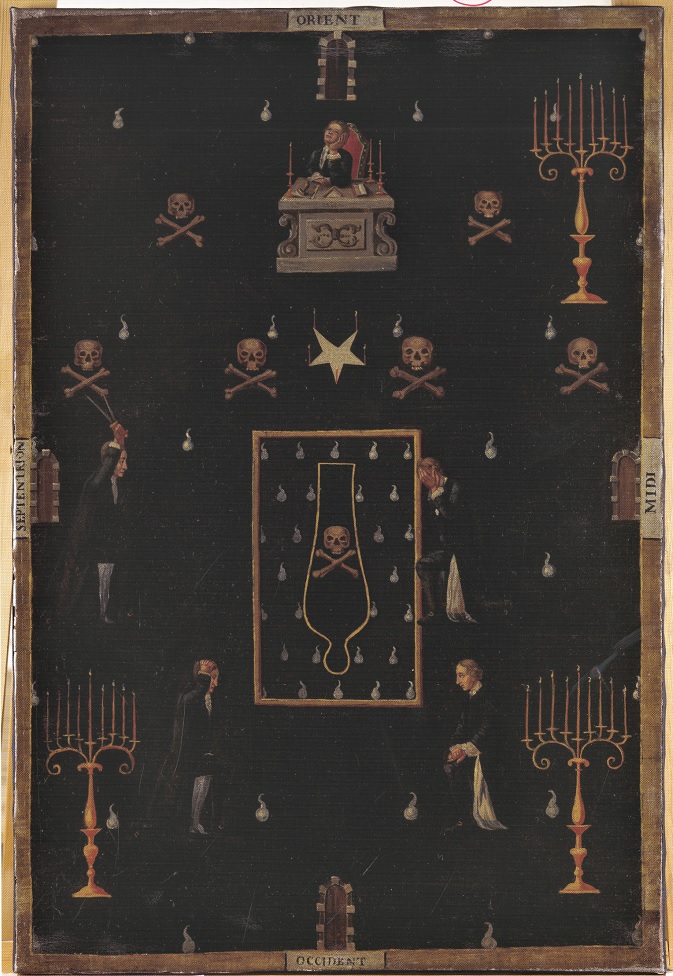

A common perception among people outside freemasonry is that the movement is creepy. A secret society with sinister symbols including skeletons and ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, secret initiation ceremonies, obscure Latin phrases connected with alchemy and strange costumes.

Freemason tapestry

Some view masonic lodges as closed shop gentlemen’s clubs where members go to eat and drink and network. Even some freemasons criticise the cronyism and self-advancement that comes to light from time to time. Accusations of antisemitism are occasionally levelled at freemasonry too – although to the Nazis, freemasons and Jews were synonymous.

Then there are the conspiracy theorists who point to masonic practises such as the secret handshakes, and the coded messages or phrases dropped into public speeches that have special meaning to masons and allow Brothers to identify themselves discretely to one another at public events. To them, freemasonry is shorthand for hidden power.

Dr Cornet tackles some of these perceptions. Long before the Second World War, German masonic lodges were accused of antisemitism because they refused to allow Jews in, he admits. Some lodges in other predominantly protestant countries like the Netherlands and the UK did allow Jews to join the movement. Germany was an exception, he says.

As for Belgium, lodges accept men and women from all faiths. “The huge majority of the roughly 27,000 Belgian freemasons are either agnostic or atheist. There are freemasons with Jewish and Muslim roots, but I doubt if they still practice their faith,” Dr Cornet says.

The secrecy surrounding the lodges is necessary, he insists. “In liberal freemasonry, the lodges are like ideas labs, where you can incubate questions and possible solutions to problems and discuss ideas in an open way. It’s not secrecy. It’s discretion, so you know that what you say in a lodge stays in a lodge,” Dr Cornet says.

Closed shop gentlemen’s clubs? It’s true that membership is usually by invitation, but Dr Cornet insists men and women can apply to join a lodge. “You can write an email to a lodge and submit a CV. Then there are discussions with an applicant to allow that lodge to get to know the person.”

Cronyism? “It’s true there are people who join freemasonry thinking they can use it to better their careers, but they soon get disillusioned and leave,” Dr Cornet says.

Conspiracies and cults

A lot of the conspiracies surrounding freemasonry come from “popular historians” with a taste for the esoteric, says Jean van Win, a historian and author of the book Bruxelles maçonnique, faux mystères, vrais symboles.

Brussels Park, also known as the Royal Park, lies between the royal palace at one end, the house of parliament at the other, with Belgium’s oldest banks located along its western side and the US embassy opposite.

Not surprisingly, given its location at a fulcrum of power in Brussels, the park feeds myths surrounding freemasonry, Mr van Win says. “The Park has been a ‘victim’ of a long series of bullshit stories about freemasonry,” he says. He blames two people in particular for dressing up wild speculation as history: Paul de Saint Hilaire and Joël Goffin.

The greatest myth about the park concerns its layout. Goffin, who claims the park is “the largest masonic space in the world”, says that the diagonal paths leading from a fountain at the Parliament end of the park were designed to imitate the masonic symbol of a compass. He outlines his theories and research in his book "Le Quartier Royal : un chef-d’œuvre maçonnique" which was published in May this year by Samsa.

To a casual observer, this may seem true – and given the park’s location it’s not surprising that the park has fed the hidden power conspiracy theories. Not so, says van Win. The Royal Park layout is a patte d’oie, or goose’s foot design first used in the gardens at Versailles, which pre-date modern freemasonry. Parks around the world have emulated this feature at Versailles. “Serious historians are clear on this. It’s definitely not a compass,” van Win, a freemason himself says.

But there are masonic links in and around the park, van Win says. One, in particular, is quite sinister. But again, it’s not all that it’s cracked up to be.

V.I.T.R.I.O.L.

Along the southern end facing the Royal Palace there are two dips in the otherwise flat park. Paths lead down roughly 15 metres to two areas of shrubs and trees that ignore the meticulous symmetry on show in the rest of the park.

On the wall facing the palace in the dip on the right, there are large wrought iron letters spelling out the word: V.I.T.R.I.O.L.. And in the dip on the left, the same word is written backwards.

“Visita Interiora Terrae Rectificando Invenies Occultum Lapidem”, or “Visit the interior of the earth and rectifying (purifying) you will find the hidden stone” appears in the chamber of reflection in a masonic lodge, where part of the initiation ceremony of new freemasons takes place.

It’s more mischievous than sinister though. The letters were erected in 1991 as part of a temporary art exhibition about symbolism. The other exhibits were taken down but the letters remain to this day.

No masonic lodge was involved with the exhibit, van Win says. “It was the work of a group of individuals. The reason it was left in place after the exhibition is simply that it was forgotten,” he says. The Royal Palace had no information about the letters. The City of Brussels Archives also drew a blank.

The first Belgian monarch, Leopold I, was a freemason, but the royal family has been staunchly Catholic since the reign of his son, Leopold II. Could the unknown group behind the letters in the park possibly be individual freemasons making a statement aimed at the royal family?

Could some Belgian freemasons just be having a bit of fun, by playing up the mystery surrounding their movement?

“I don’t think so in a formal sense, but some freemasons may like to play with that idea,” says Dr Cornet.

But it is the more serious side of Belgian freemasonry that has caught the attention of freemasons around the world. Shawn M Gormley, a freemason and academic from Pennsylvania has urged his brothers to look to Belgium for inspiration, pointing to the story about Liberté Chérie, the lodge set up inside the Nazi prison camp at Esterwegen. “If you are a member of a stale and boring lodge, let me ask you this; after what you just read, are you content with your Lodge remaining stagnant and stale, or are you going to honour our Masonic brothers who have been persecuted and killed because of their devotion to our craft,” he wrote.

Freemasonry: a potted history

What is freemasonry? In some ways, it is like a religion. Many freemasons believe in God. There are strange rituals, odd costumes, ancient history and temples. Like monks and nuns, freemasons – in Belgium at least - call each other brother or sister.

But it isn’t a religion. In fact, over time, it became the antithesis of Roman Catholicism in Belgium and other predominantly Catholic countries in Europe (see main article).

Freemasonry’s history is puzzling. Some historians trace its roots to the craftsmen’s guilds of the Middle Ages, whose crests adorn the beautiful facades around the Grand Place in Brussels. Others claim it is inherently Christian, and dates back to the Crusades.

But early 18th century masonic orthodoxy dates its origins far further in time.

Related News

A thousand years before Christ, King Solomon of Israel is believed to have built the first Temple of Jerusalem on the Temple Mount, which today is the location of the Al Aqsa Mosque and the Wailing Wall (the remains of the Israelites second temple). The building, which is said to have housed the Ark of the Covenant, was an architectural marvel. When modern freemasonry was born in the early 18th century, Solomon was considered the first Grand Master of freemasonry.

The first Temple of Jerusalem became a metaphor for perfection. “The aim of freemasons is to build a temple of humanity – an ideal that begins within each individual, but extends to society,” says Dr Cornet. Many masonic symbols feature the tools of the stonemason: the compass and the square, for example.

Freemason tapestry

In 1717 four masonic lodges in London joined together to form a federation – the Grand Lodge of London. Six years later James Anderson drafted a Constitution of Freemasonry. The movement spread rapidly around the British Empire, including the United States, and also to neighbouring countries in Europe and beyond.

Freemasonry took root in Belgium in 1833, with the founding of the Grand Orient of Belgium, but its influence here began in the 18th century when the country was part of the Austrian Netherlands, and later during French rule.

The Belgian Museum of Freemasonry is a treasure trove of artifacts and documents chronicling the movement’s presence in Belgium. The museum’s recently appointed curator, Annick Born, says she wants to make freemasonry more transparent, while striking a balance between the mysticism and the history.

An academic from Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) and Ghent University, Born is not a freemason herself, but is committed to opening up the movement in Belgium. “It’s not a dark society,” she says. “There are normal people in it. Here in Brussels, we are at the centre of modern Europe. There are lodges working in different languages – English and Italian, for example.”

Born also wants to draw attention to what freemasonry is doing to improve society: the mystical side is still there, but the focus is shifting to the here and now. “My aim is to explain what freemasonry does,” she says.

Famous Belgian freemasons past and present

King Leopold I - monarch

Felicien Rops – painter

Elio di Rupo – politician

Anne-Marie Lizin – politician

Jean Rey – politician

Victor Horta – architect

Henri Jacobs - architect

Pierre-Theodore Verhaegen – founder of the ULB

Guy Spitaels – politician

Jules Bordet – scientist

Charles de Coster – novelist

Isabelle Gatti de Gamond – educationalist, feminist

Roger Lallemand - politician

Jules Ansbach - politician

Famous freemasons from around the world include Voltaire, Rudyard Kipling, Sir Christopher Wren, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, Winston Churchill, George Washington, Franklin D Roosevelt, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, Mark Twain, Sir Alexander Fleming and André-Gustave Citroën.