When Charlotte Brontë left Brussels in 1844 after her two-year stay at the Pensionnat Heger, the future author of Jane Eyre returned to her Yorkshire village of Haworth with her head crammed with impressions she would set down in her novels.

She departed Belgium, too, with her heart in a turmoil of feelings for the man who had tutored her in French language and literature – Constantin Heger, father of six, husband of the directress of the boarding school where Charlotte had been perfecting her French and teaching English.

Back in Haworth, she employed her newly honed language skills in a barrage of emotional letters to her former tutor. When he proved unresponsive, she sought consolation by using him as the model for fictional heroes such as Jane Eyre’s Mr Rochester.

Charlotte Brontë took back to England not just a throng of impressions and emotions, but a travelling trunk packed with Brussels mementoes, the most treasured of which were gifts from Heger. He had presented his star pupil with books and copies of stirring, patriotic speeches he had made at the annual prize-giving for pupils at the Athénée Royal, the prestigious boys’ school where he taught.

But Charlotte’s trunk also contained a more unexpected offering from her tutor, a piece of wood measuring about ten by two centimetres that would look utterly insignificant did it not bear an inscription in ink that read “morceau du cercueil de Ste. Hélène”.

This tiny strip of wood, now one of the most curious items in the Brontë Parsonage Museum, is a fragment from the coffin of Napoleon Bonaparte, who had been buried in 1821 on his island exile of St Helena.

How did Heger come to own a relic that Napoleon devotees would have been thrilled to have in their possession? Happily, it is possible to trace the intriguing and somewhat circuitous route by which it came into his hands and thence to Charlotte Brontë’s.

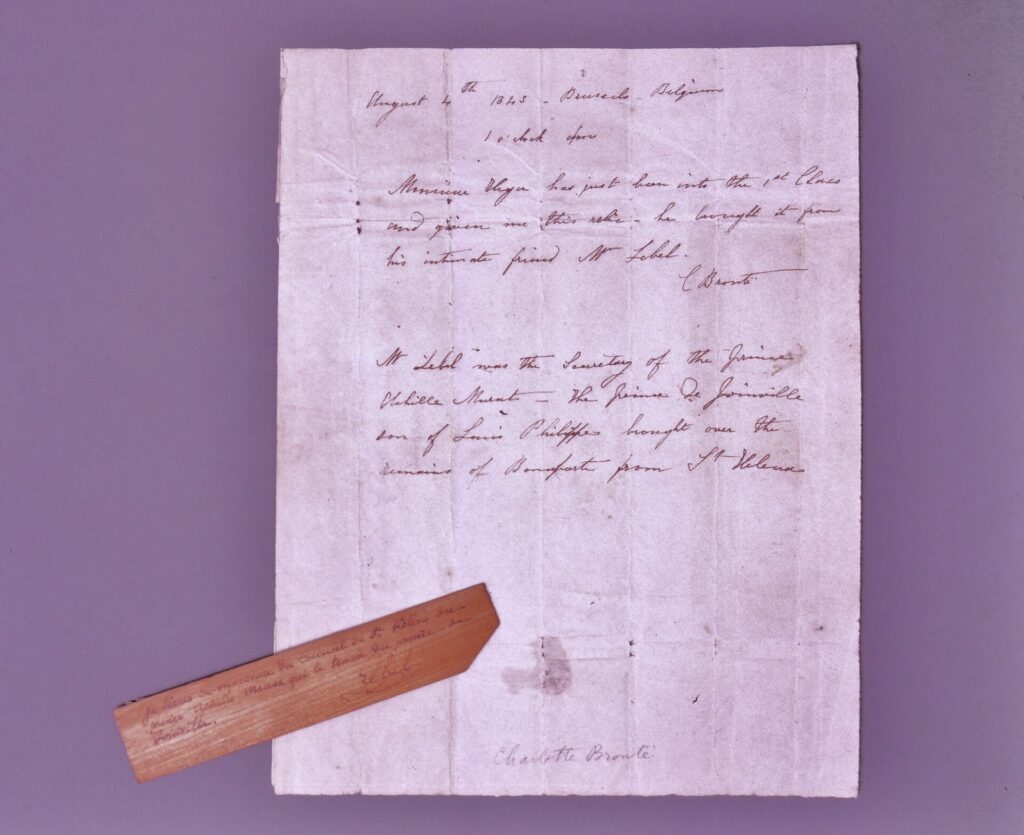

The coffin fragment and the letter from Heger, now at the Brontë Parsonage Museum

The relic had a paper wrapping which has been conserved in the Brontë Museum and on which Charlotte wrote: “August 4th 1843 - Brussels – Belgium - 1 o'clock pm. Monsieur Heger has just been into the 1st Class and given me this relic – he brought it from his intimate friend Mr Lebel. Mr Lebel was the Secretary of the Prince Achille Murat; the Prince de Joinville, son of King Louis Philippe, brought over the remains of Bonaparte from St Helena.”

Lebel was a colleague of Heger’s at the Athénée, a Frenchman on whom Charlotte is believed to have modelled an unsavoury character in her novel The Professor. The full inscription written by him in ink on the wood reads “Je tiens ce morceau du cercueil de Ste. Helene du prince Achille Murat qui le tenait du prince de Joinville. Lebel.” Thus, we have the names of the actors through whose hands the fragment passed to Heger and from him to his devoted pupil: the schoolmaster Lebel, a certain Prince Achille Murat, and the Prince of Joinville.

Why Napoleon?

Before looking at these three Frenchmen and the relic’s passage through their hands it is worth asking why Heger should have chosen Charlotte as its recipient. Was she an admirer of the late emperor?

She would certainly have welcomed the present as a sign of esteem from Heger, particularly at a time when she felt he was increasingly avoiding her. She suspected Madame Heger of keeping her husband away from her. Only days later, when the summer vacation began, his gift could not raise her spirits as she faced the prospect of remaining in Brussels without him while he and his family holidayed on the coast. Loneliness and depression drove her, a Protestant, to persuade a Catholic priest to hear her confession in the St Gudule cathedral.

Apart from its sentimental value as a gift from Heger, the coffin fragment would have been of interest to her as a relic of the man himself. Napoleon had loomed large in her consciousness since early childhood. His defeat at Waterloo in 1815 took place the year before Charlotte’s birth, but she and her siblings shared their father Patrick’s fascination with the Napoleonic wars of his youth. They also shared his admiration of the Duke of Wellington, victor of Waterloo and vanquisher of the French emperor.

The children’s imaginary adventures were first inspired by a set of toy soldiers. Charlotte chose one as her own and named it Wellington, brother Branwell called his Napoleon. These historical personages morphed into fictional characters whose battles and loves were narrated by the young Brontës in tiny notebooks.

When Charlotte and her sister Emily arrived in Brussels in 1842, Waterloo was still a not-so-distant memory and the battlefield was of course close by. Surprisingly, the sisters do not appear to have visited it, but Napoleon was very much present in the classrooms of the Pensionnat Heger.

It was only a couple of years earlier, in 1840, that his remains had been brought back from St Helena and ceremoniously reinterred in Les Invalides. King Louis-Philippe’s decision to allow this revived Napoleonic hero worship. A schoolfellow of Charlotte’s at the Pensionnat recalled a classroom dispute when the other pupils lambasted her for Britain’s conduct in banishing the late emperor to the gloomy South Atlantic island.

Charlotte got her own back in a French essay for Heger titled The Death of Napoleon, vindicating the exile to St Helena and denouncing the emperor’s rapacious ambition. Wellington, she argued, was prompted not by revenge but by the need to avoid further war in Europe. She contrasted Bonaparte’s thirst for popularity and glory with the Duke’s modesty and indifference to public opinion in doing what he believed to be right. Wellington’s glory, concluded Charlotte, would last. Napoleon’s would not.

Charlotte Brontë

Given Heger’s knowledge of Charlotte’s opinions, one can imagine an amused smile on his face as he laid the Napoleonic relic on her desk. In later years, when he read her novel Villette and recognised himself in its schoolteacher hero Monsieur Paul, he would have noted that Monsieur Paul “had points of resemblance to Napoleon Bonaparte.”

It is not clear whether the gift of the coffin fragment was Heger’s idea or that of its owner, his colleague Lebel. Joachim Joseph Lebel, one of numerous French émigrés living and working in Belgium, was director of the boarding house for pupils of the Athénée Royal. If, as is believed, Charlotte took him as inspiration for M. Pelet, the French school director in The Professor, it is to be hoped that some of Pelet’s traits were the products of her lurid imagination. When Pelet’s fiancée, directress of a girl’s school, falls for Pelet’s employee William Crimsworth, the Frenchman becomes wild with jealousy and attacks Crimsworth in a drunken frenzy.

Brussels, city of French plotters

How did Lebel come to acquire the coffin fragment? In the 1830s the young Frenchman was friends with another French émigré then in Belgium: Achille Murat, a nephew of Napoleon’s and one of the most colourful members of the Bonaparte family. He was the son of Napoleon’s sister Caroline and of Joachim Murat, a dashing cavalry leader whom Napoleon made King of Naples.

Murat senior lost his throne to the Bourbons and was executed by firing squad after a failed attempt to take it back. Prince Achille (Murat junior), a restless, adventurous soul, was one of the swarm of Bonaparte relatives in exile intriguing to return to power. Along with various other Bonapartes, he had made a life for himself in America and married a great-grandniece of George Washington. But in the wake of the 1830 July Revolution that toppled the Bourbon restoration in France and brought the liberal Louis-Philippe to the throne, he made his way to Europe.

In the months after Belgium’s own 1830 revolution, when the newly independent country was looking for a king, some Bonapartist intriguers thought of Murat as a pretender for the Belgian throne. Instead, Leopold I was chosen. Shortly after Leopold’s swearing-in, Murat went to Belgium. Pending an opportunity to fight for Italian nationalism, he reckoned he could see military action by helping Leopold fight the Dutch, who were refusing to recognise Belgian independence. However, the scheme ultimately failed: war never came and he returned to the US.

Lebel came to Belgium in 1830, but before he turned schoolmaster he was a sergeant in Murat’s ill-fated regiment of foreign soldiers and remained attached to him as a kind of secretary, carrying out commissions for the Bonaparte adventurer. Their friendship continued after Murat’s return to America. Murat visited Paris in 1841 shortly after Napoleon’s reinterment; it may have been on this visit that he acquired the coffin fragment he passed on to Lebel.

But which coffin did it come from? About this, there is some doubt. Napoleon was famously interred on St Helena not in one but in several, nested, coffins, as described by members of the party who accompanied, Prince of Joinville on the frigate Belle Poule, for the mission known as ‘le retour des cendres’.

When the expedition party arrived at St Helena the coffin or rather coffins were opened to identify and check the state of the corpse, which was found to be in surprisingly good condition. The body had been buried in four coffins in the following order: tin, mahogany, lead and mahogany. The outer mahogany one had to be broken up to penetrate the others and was discarded.

The three remaining ones were placed in three new ones brought from France made of lead, ebony and oak. The remains were thus borne back to France in no fewer than six coffins. The outermost oak one, however, was no more than a protective casing used for transferring the remains to the ship and was discarded once they were safely on board.

The discarded mahogany and oak coffins were both cut into pieces which were distributed as souvenirs among the crew and passengers of the Belle Poule. The appearance of Charlotte’s fragment suggests it might have been from the oak casing rather than the mahogany one, but the type of wood has not been established.

As Charlotte sat in the train pulling out of Brussels with her Napoleonic relic in her trunk, she could not have dreamed that in little over ten years her fame as the author of Jane Eyre would be such that Brontë relics would already be circulating among her fans. Her death in 1854 at the age of 38 began a stream of literary tourists to Haworth that continues to this day. Her father cut up her letters and distributed the snippets to admirers demanding samples of her handwriting.

When the parsonage was being renovated after his death, an American visitor purchased a windowpane and a section of panelling from Charlotte’s bedroom. He used the glass and wood for framing pictures so that he could look at them through the glass Charlotte had gazed through when at her window. Such veneration for the Brontës and anything belonging to them rapidly spawned an industry in ‘Brontëana’ and Charlotte Brontë, rather like Napoleon Bonaparte, became the subject of a cult.