He was born as Jozef de Veuster in 1840 in Tremelo, a small village in Flemish Brabant. Better known as Father Damien, he worked as a missionary in Hawaii between 1864 – 1889 during a critical period of its history when it was colonised by the US and its population decimated by infectious diseases.

For 16 years, Father Damien dedicated his life to the people with leprosy on Molokai, an island in Hawaii, until he succumbed himself to the disease. In 2009, he was canonized by the Catholic Church as Saint Damien of Molokai. Father Damien has become a legend in both Belgium and Hawaii and achieved the status of national hero in both countries.

In 2005, he was chosen by the TV audience of the Flemish broadcasting company as the greatest Belgian of all times (“Grootste Belg”). In a similar poll organised by the French-speaking broadcaster in Wallonia, he came in third place (“Plus grand Belge”).

In the US, each state is represented by two statues in the National Statuary Hall in the Capitol building in Washington. The statues depict persons “illustrious for their historic renown or for distinguished civic or military service, as each State may deem worthy of this national commemoration.”

During the colonial era, the missionary movement played a significant role in Belgium, and it is estimated that 10% of all Catholic missionaries around the world were Belgian. Damien became far more than just a “converter” however, and may have acted more as a human rights defender in a colonial world when this concept did not exist. Loved and respected by the Hawaiians, his shrine is well visited today, and inspires locals and visitors from around the world.

Hawaii chose to send statues of Father Damien, an immigrant and non-native who became one of their own, and King Kamehameha I, the ruthless founder of the Kingdom of Hawaii in 1810. Both statues were unveiled in the Capitol Rotunda on 15 April 1969.

The day is also the day when Father Damien passed away and is celebrated annually in Hawaii as Father Damien Day. To the Hawaiians, he embodies the fundamental values of family and community (ohana), of attention and care for each other (malama pono) and of love and solidarity reaching across borders (aloha).

Recent controversy

It came therefore as a surprise during the coronavirus crisis when an American politician, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez – a Democratic member of the US House of Representatives – singled out Father Damien as a symbol of “patriarchy and white supremacist culture.” Or maybe it was not a surprise considering the demands to tear down or remove statues of American-Confederate generals, European slave traders and King Leopold II who colonised Congo.

“Even when we select figures to tell the stories of colonized places, it is the colonizers and settlers whose stories are told – and virtually no one else,” she wrote on Twitter, besides a photo of Father Damien. “This is what patriarchy and white supremacy culture looks like! It’s not radical or crazy to understand the influence white supremacist culture has historically had in our overall culture and how it impacts the present day.”

Her remarks sparked an uproar, and, facing worldwide criticism, she was forced to retract. “At no point did I say Fr. Damien was a bad figure. It’s about the fact that a huge supermajority of statues in the Capitol are white men. Barely any women or BIPOC (black, Indigenous and People of Colour).”

“It was quite common in the 19th century to become a missionary,” explains Ruben Boon to The Brussels Times, director of Project Damiaan Vandaag in Leuven, a project run by the same Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, which Father Damien had joined. The Congregation works closely with the Father Damien Museum in Tremelo to keep the legacy of Father Damien alive.

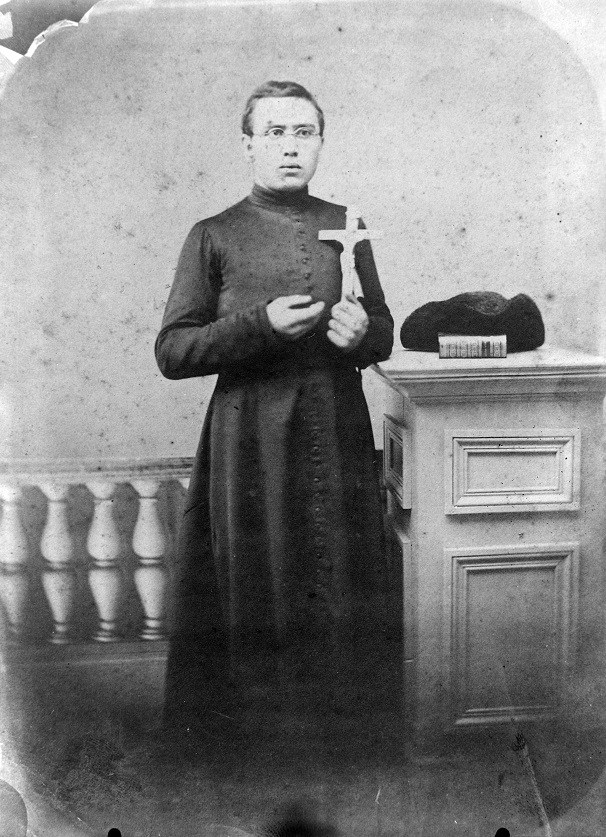

Father Damien in Paris before his departure to Hawaii, October, 1863. Credit: SS.CC., Leuven

”Father Damien was definitely not the only missionary who left his motherland at a young age. There were many male and female missionaries who did the same thing but are much less known. The missionary movement from Belgium was actually very common in the 19th century and also continued strongly in the first half of the 20th century,” says Boon.

How can we understand Father Damien's motives and beliefs from his diaries or letters?

“Father Damien's motives and beliefs were very clear,” Boon replies. “In his farewell letter to his parents and family, when he left Europe for Hawaii, he stated that he went there to spread the gospel and convert the people.” He was not unaffected by European cultural prejudices and believed in Christianity, especially Catholicism, as the only way to redemption.

Not a typical missionary

But Damien became far more than a converter. After his arrival in Hawaii, he studied hard to learn the Hawaiian languages and to become a priest. He arrived in March 1864 in Honolulu after a boat trip of five months. By May 1864, he was already ordained as priest. Shortly thereafter, he was sent as a missionary to the biggest island of the Hawaiian archipelago.

He did there what every “classical” missionary did in those times: baptizing people, teaching religion, celebrating mass, organizing processions, visiting the sick, spreading the gospel and converting people. As a very practical person, using his skills from his farm life in Belgium, he even built churches and chapels.

“Damien was a special person and built up a strong and affectionate relationship with the Hawaiians despite the prevailing colonial mindset. He spoke with the Hawaiian people in their own language, visited them in their homes and stayed with them for dinner. He was there for them when they needed him and cared for them. He started to love the Hawaiian people, and they felt the same way about him,” says Boon.

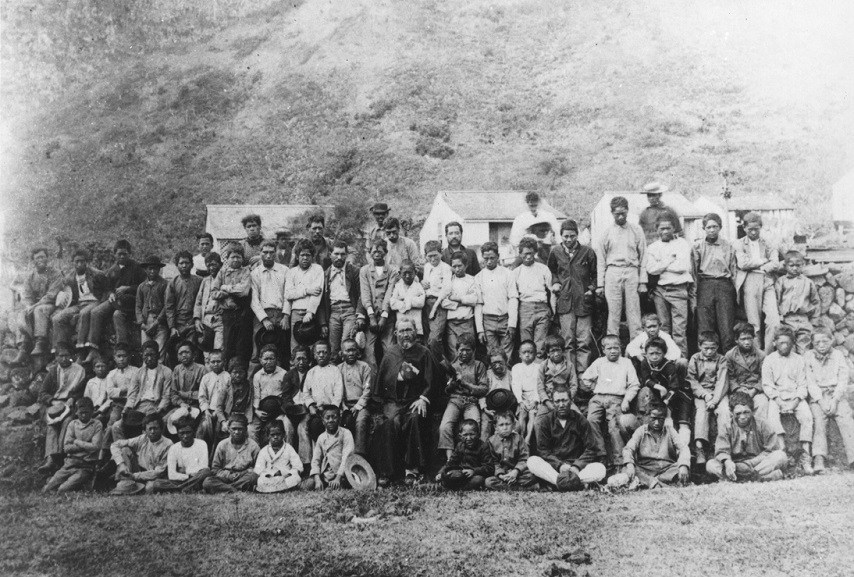

Father Damien with a choir, Molokai 1878. Credit: SS.CC., Leuven

This might explain his own transformation from a typical missionary to a social worker and activist. He reacted against the ruling that every person who was infected with leprosy should be turned in and sent away to a natural prison on the island Molokai. Hawaiian families were torn apart by this ruling. The act was against Hawaiian cultural values that prescribe society to take good care of sick people and not to send them away.

“Father Damien saw the pain and suffering of these families and became another person and another kind of missionary,“ Boon says. “He wasn't any longer a converter of souls in the first place. He became a religiously inspired activist defending the cause of the Hawaiian people. He chose their side against the warnings of his superiors and volunteered to assist the sick people in the leprosy colony of Molokai.”

In fact, he had committed himself to do whatever it takes to help people in need already when he took his religious vows. “In Molokai, he shared his life with incurably sick people and gave his life for them. He took care of their physical, psychological and spiritual needs, organised their social life and became their voice to the outside world.”

Against all odds, Father Damien tried to build a miniature model community in which every person was respected and taken care of, as part of one family or ohana (Hawaiian for family). Most of the time there was no resident physician or nurse in the colony. Eager to find a cure for leprosy, Father Damien corresponded with physicians abroad and experimented with medicines.

Father Damien, Molokai 1889. Credit: SS.CC., Leuven

Because of his differences of opinion with his hierarchy, he was often accused by them of disobedience, but Ruben Boon thinks that this is a misunderstanding, which has been refuted by research. “It’s true that Damien was strong-tempered, and it wasn't always easy to get along with him. But everybody who knew him better, admitted that he had a good heart and that he was ready to apologize. He wasn’t at all a quarrelsome person and had good relations with his first bishops and superiors.”

But the hierarchy did not understand the very special conditions in Molokai and might have envied him. In 1881, Father Damien was appointed to Knight Commander of the Royal Order of Kalākaua by Princess Lili'uokalani, the future queen of Hawaii. The international attention he received for his work in the leprosy settlement would overshadow the rest of the mission in Hawaii.

Legacy

Father Damien was proposed for beatification already after his death but it would take until 1995 and then to 2009 until he was canonised by Pope Benedict XVI. King Albert II of Belgium was present with Queen Paola at the ceremony to mark his canonisation. While no miracles are linked to him, his whole life was considered a miracle.

“It is difficult to say why it took so long,” Boon says. “He was a kind of a rebel who had clashed with his superiors in Hawaii and in Europe and that might be an explanation.” But in Belgium, Father Damian was admired both during his lifetime and even more after his death in 1889.

“The first statue of him was raised in Leuven in 1894,” explains history professor Idesbald Goddeeris at KU Leuven. “When his bodily remains were brought back to Belgium in 1936, they were received by the Belgian king. After a journey around the country, the remains were laid to rest in Saint Anthonus’ Chapel in Leuven. On the centenary of his voyage to Hawaii, a new statue was erected in Tremolo in 1963.” Currently, Flanders has more than ten outdoor statues, certainly six indoor statues (mostly in churches) and at least 28 streets or squares named after Father Damien or Jozef De Veuster, he adds.

Father Damien Statue in front of the Hawaii State Capitol. Credit: Daniel Ramirez

Professor Goddeeris teaches colonial history and has studied postcolonial debates in Belgium and the memory of missionaries. “Every Belgian knows about Father Damien from early school years. He is looked upon as an inspiration for all and has become an important figure in Belgium, even in Wallonia, which is less Catholic than Flanders.”

“Father Damien is regularly commemorated, not only in religious ceremonies but also in a secularized way, because his life transcends national and religious boundaries and everyone can identify themselves with him,” he adds. In the 60s, in the wake of decolonisation, a medical charity NGO (Damien Action) was formed in his memory.

Both Ruben Boon and Idesbald Goddeeris admit that the colonial context in the 19th century should be taken into account and that colonialism and the missionary movement are interlinked. On the one hand, missionaries tried to protect and help the native population, on the other hand they were also part of colonialism.

But in the case of Hawaii, the European missionaries there were not sent by European colonial powers to promote their interests. It was the American missionaries and their descendants who played a double role, overthrew the Kingdom of Hawaii by the threat of force in 1893 and paved the way for the US annexation of Hawaii.

Hawaii became an American territory, or colony, with a small minority of native Hawaiians who had survived the diseases that foreigners had brought to the islands. Its status changed in 1959 when it became a state. The memory of the suppression of Hawaiian culture and the illegal annexation of Hawaii is still a painful memory that was recognized by the US congress in 1993 in the Apology Resolution.

In the non-binding resolution, Congress conceded that "the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the US … The Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the US their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaii or through a plebiscite or referendum."

What about the remarks of Ocasio-Cortez? “She has a point that there are many white men among those statues in Washington,” admitted Ruben Boon. “And Damien was undeniably a white man. But the choice of Damien as an example of white male supremacy weakened her own argument.”

“Damien was not a white ruler. He spoke the language of the Hawaiians. He deliberately chose their side against the white rule. He eventually gave his life for them. In that sense – even for the Hawaiians themselves – he is much more Hawaiian than Belgian, white or whatever.” Inspired by his Christian faith, Father Damien was a human rights defender in a colonial world when this concept did not exist.

Father Damien: a short biography and historical background

Belgium had only existed as an independent country for less than ten years when Jozef – the future Father Damien – was born on 3 January 1840 in Tremelo, a village 17 km north of Leuven. His life can be divided into three distinct periods: his childhood and upbringing in Belgium and his joining a religious congregation (1840 – 1864), his first years as an ordinary missionary in Hawaii (1864 – 1873) and his work as a priest-social activist until his death at the leprosy colony in the island Molokai (1873 – 1889).

It was a turbulent period, politically, socially and economically with new technical inventions. In Belgium, the Catholic church took advantage of the freedom of education, association and press to expand its influence over society. Many new religious congregations were founded, just as in France and other countries in Western Europe.

One of them was the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, which opened its first house outside France in Leuven in 1840, the birth year of Jozef. At that time, choosing a religious calling meant becoming “born again” and receiving a new name and even identity. These religious organisations did not stay confined in monasteries but worked hard in the local community to provide education, health care, and assistance to the poor – social services that are taken for granted in modern welfare states.

Jozef grew up in the Flemish part of the country, speaking Dutch. He attended secondary school in the Walloon part of the country, being taught in French. His parents were farmers and traders, religious, enterprising and progressive. He was the youngest of three brothers and four sisters in a Catholic family. His parents hoped that he would take over the farm while other siblings would choose a religious profession. But at the age of 19, he was convinced by his brother to enter the same congregation as he had done, the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary. By doing so, Jozef also changed his name to Damien and studied to become a priest at the congregation’s headquarters in Paris.

Father Damien’s parental home in Tremelo. Credit: SS.CC., Leuven

He dreamt about missions far away but it was a pure coincidence that he went to Hawaii. His brother had been chosen to go to Hawaii as a missionary but he fell ill and Damien took his place though he had not yet been ordained as a priest.

From Europe, Catholic and Protestant missionaries travelled to all the continents as messengers of the faith, to spread the Christian religion and bring “Western civilisation” to other parts of the world. Missionaries of different confessions competed for saving the souls of unbelievers. In fact, the missionary movement played a significant role in Belgium and it is estimated that 10% of all Catholic missionaries around the world were Belgian.

When Father Damien arrived in the Hawaiian Islands in March 1864, he was introduced to a vibrant and multicultural society – a product of the fast-paced nineteenth century, with all its changes. At the beginning of the century, King Kamehameha I had unified the Hawaiian Islands into one kingdom. The US, Great Britain and France tried to strengthen their hold on the islands.

A white minority of missionaries and businessmen, descendants of the first Protestant missionaries who had arrived from the US in 1820, dominated the native Hawaiian people. Western worldviews, capital and products influenced the Hawaiians and replaced the Hawaiian culture.

The missionaries revealed themselves to be either accomplices of the foreign powers or activists for the Hawaiian people. According to Hawaiian history professor Jonathan Osorio, a class of “haole” (non-native or white) businessmen, which made up a small minority of the population, dominated the government in the 1880s.

In fact, Hawaii’s encounter with the outside world started with British explorer James Cook’s landfall in 1778. As happened centuries earlier when the Spanish colonised America and brought diseases which would decimate the local population, the same happened in Hawaii. Cook’s crew introduced sexually transmitted diseases.

Because of their isolation, the Hawaiians lacked immunity to these and other infectious diseases like measles and smallpox. Hit by waves of epidemics, the Hawaiian population was drastically reduced during the nineteenth century and almost wiped out. Even the royal couple Kamehameha II and his queen Kamamalu, who visited London in 1824, were infected with measles and died there.

In his letters home, Father Damien was aware that the Hawaiian population was being decimated by disease. When he worked as a missionary in the Hawaiian Islands, the spread of leprosy claimed many Hawaiian victims.

The local government reacted with a policy of isolation and confinement in an attempt to halt the epidemic. Since the beginning of 1865, a Hawaiian law stipulated that all persons infected with leprosy had to be deported to two settlements, Kalawao and Kalaupapa, at the northern end of the peninsula of the island of Molokai, which functioned as a natural prison.

According to Anwei Law, a Hawaiian author who has studied the history of Molokai, an estimated population of 8,000 inhabited the leprosy settlements between 1866 and 1969. At least 90% of them were native Hawaiians. Father Damien wrote in his letters that there were 700-800 people with leprosy during his first years there and that he buried 190 – 200 every year.

In 1873, the year Father Damien volunteered to share his life with the deported Hawaiians, the Norwegian doctor Gerhard Hansen discovered the leprosy bacillus. But for the remainder of the nineteenth century, scientists were unable to find a cure, and it would take several decades until antibiotics were found that would eradicate leprosy from the world. With early diagnosis and treatment, the disease can be cured today.

During his lifetime, Damien continued to work hard to improve the living conditions and quality of life of the leprosy patients. He received support and sympathy from the Hawaiian authorities, the royal family and the outside world, but met also opposition, slander and envy from within the Church and its hierarchy.

By Mose Apelblat