An international research team of planetary scientists working at the Belgian Princess Elisabeth Station in Antarctica has made a major geological discovery, finding new evidence for a meteorite airburst just above the Antarctic ice cap 430,000 years ago.

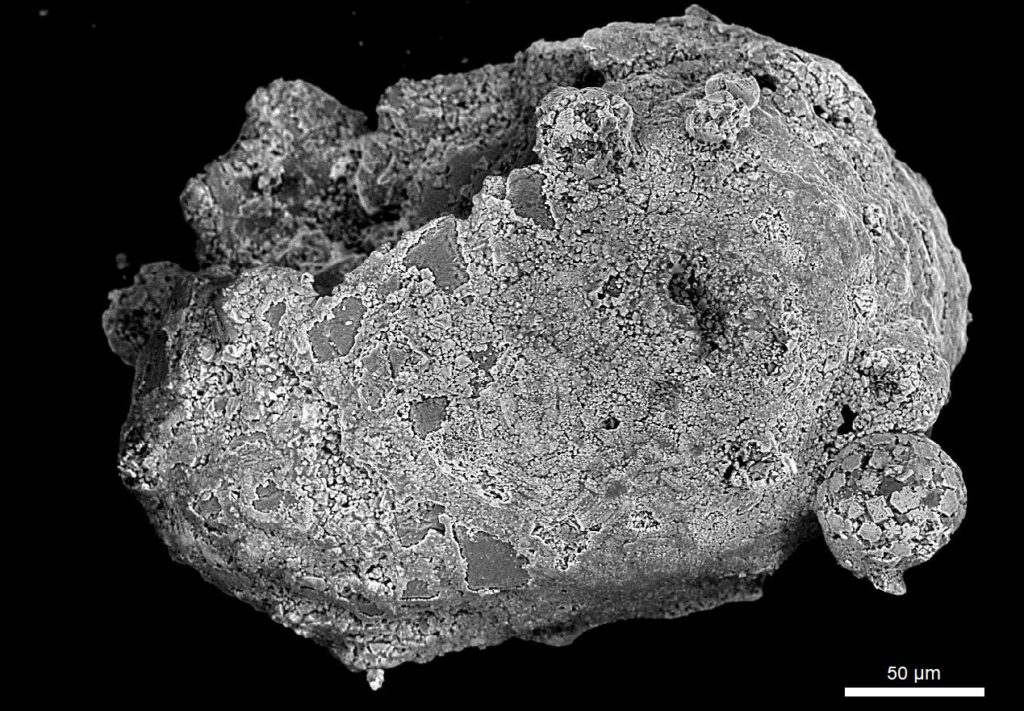

“What we found at the very tops of mountains in east Antarctica were these really small particles in these sedimentary traps where we normally look for micrometeorites and other extra-terrestrial dust,” Dr Steven Goderis, a Belgian Research Professor at VUB, told The Brussels Times.

“When we found these small particles, we realised these were quite special - that they were part of something much bigger.”

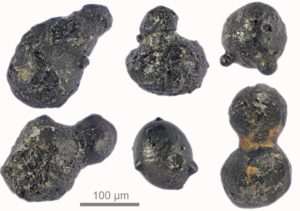

The particles look a bit like the barbells used in weightlifting, which Goderis said is the result of colliding with one another in a cloud of dust and gas during an airburst close to the ice’s surface.

“This is very atypical. It means these things collided with each other. Because you had this explosion so very low to the surface, basically the momentum of the material was not lost and you had jets moving onwards at the same velocity. This led to melting of the ice sheet and the production of these melted and condensed particles that stuck together.”

Photographic image of the extra-terrestrial particles discovered by the research team in the Sør Rondane Mountains, near the Princess Elisabeth Station in Antarctica (credit: Scott Peterson/micro-meteorites.com)

That type of explosion, said Goderis, has less destructive power than the formation of an impact crater might have, but is still significantly larger than when it occurs at a higher altitude, which in most cases is 30 to 50 kilometres.

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, is an important discovery in the field of geology where evidence for such events is scarce. Such impact particles are generally difficult to identify and characterise.

“But in this case, the atypical shape of the condensation particles made it relatively easy to distinguish them from other extra-terrestrial dust particles found in Antarctica, such as micrometeorites and microtektites. The results of this research can therefore help to identify similar events in the geological past,” said VUB PhD student Bastien Soens, co-author of the study.

The discovery came after what was, for Goderis, a fifth visit to the frozen continent.

“Antarctica for us has been this treasure trove,” he said. “The Princess Elisabeth Station is located in the Sør Rondane Mountains of Eastern Antarctica and not a lot of people have worked on this type of topic over there before.”

Getting to the research site where they discovered the meteorite evidence takes a full day of travel on snowmobiles, leaving only a few hours to sample and then get back to the station.

“It's cold and tough, but it’s also fun. It's all worth it, basically, when you have a nice research result like this. It takes a while to get there, multiple years often, but then every once and a while you find something so unexpected, it's really worth the effort.”

And here is a photo of the three adventurers, Alain Hubert, @GoderisSteven and @Matthias_vangi, who braved Antarctica to find impact spherules on top of Walnumfjellet! pic.twitter.com/uusF7tDrCr

— matt van ginneken (@Matthias_vangi) March 31, 2021

The study underlines the importance of mapping the threat posed by medium-sized asteroids as accurately as possible, since future objects of a similar size are likely to explode in the atmosphere and generate a shockwave.

If an explosion were to occur too close to the Earth’s surface, the damage could be severe, especially in densely populated areas.

“We know that this happens every 1,000 to 5,000 years,” said Goderis. “Another problem with these smaller ones is that you can't see them coming. It’s really difficult to have ground tracking programs detect these sizes of asteroids. Still, 5,000 years is a long time, of course.”

After passing through the atmosphere, meteoroids larger than 100 metres can form an impact crater in the Earth’s crust, but they will more often explode in the air and cause a powerful and destructive shockwave.

The best-known example of such an event is the much smaller Chelyabinsk impact over Russia in 2013, which destroyed a huge number of windows. The Tunguska event, also in Russia but in 1908, produced an even larger shockwave that toppled trees over an area of 20 square kilometres and caused major damage up to 100 kilometres from the site.

Tiny particles tell a big story!https://t.co/1xzRsPgjai

Shout-out to Mark Garlick @SpaceBoffin pic.twitter.com/Uw2jGRcxmm — Steven Goderis (@GoderisSteven) March 31, 2021

The new discovery in Antarctica is a major one because of how important it is to try to identify these types of events in order to assess their frequency and better identify potentially dangerous asteroids in terms of size and speed.

“If such an explosion were to take place over a region with a large population, it would be absolutely catastrophic, with a huge number of casualties,” said VUB professor Philippe Claeys.

The research was led by Dr Matthias van Ginneken of the School of Physical Sciences at the University of Kent, a former researcher at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, the Université libre de Bruxelles, and the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.