Amid the opulence of 15th century Bruges – a city alive with trade, textiles and the patronage of dukes – the Book of Hours became an unlikely literary sensation.

Compact and portable, yet often richly adorned, these devotional manuals bridged private piety and public prestige. A new publication, Books of Hours, Books of Hope, curated by the Public Library of Bruges, explores these artefacts not just through scholarship, but through sight.

Originally designed as simplified versions of monastic liturgy, Books of Hours offered a daily rhythm of prayer to the Virgin Mary and other sacred figures. They sanctified the hours from Matins before dawn to Compline at nightfall.

But as the images on these pages show – from intimate miniatures of Christ’s Passion to the elaborate trompe-l’oeil rosary beads inked into margins – their purpose extended beyond devotion. The illuminations would have guided prayer and reflected pride. These books were expressions of personal identity, talismans of protection, and, for the wealthy, status symbols as finely crafted as jewellery.

Bruges was a powerhouse in this trade. Its Guild of St John the Evangelist brought together scribes, illuminators, binders, and stationers into a bustling manuscript industry. The modular production methods illustrated in the accompanying photos – with miniatures, text blocks and decorative borders created separately and later assembled – reveal a surprisingly modern efficiency. Among the most touching details in the book are signs of use: wax stains, thumbed corners, and inked marginalia that turn each copy into a lived artefact.

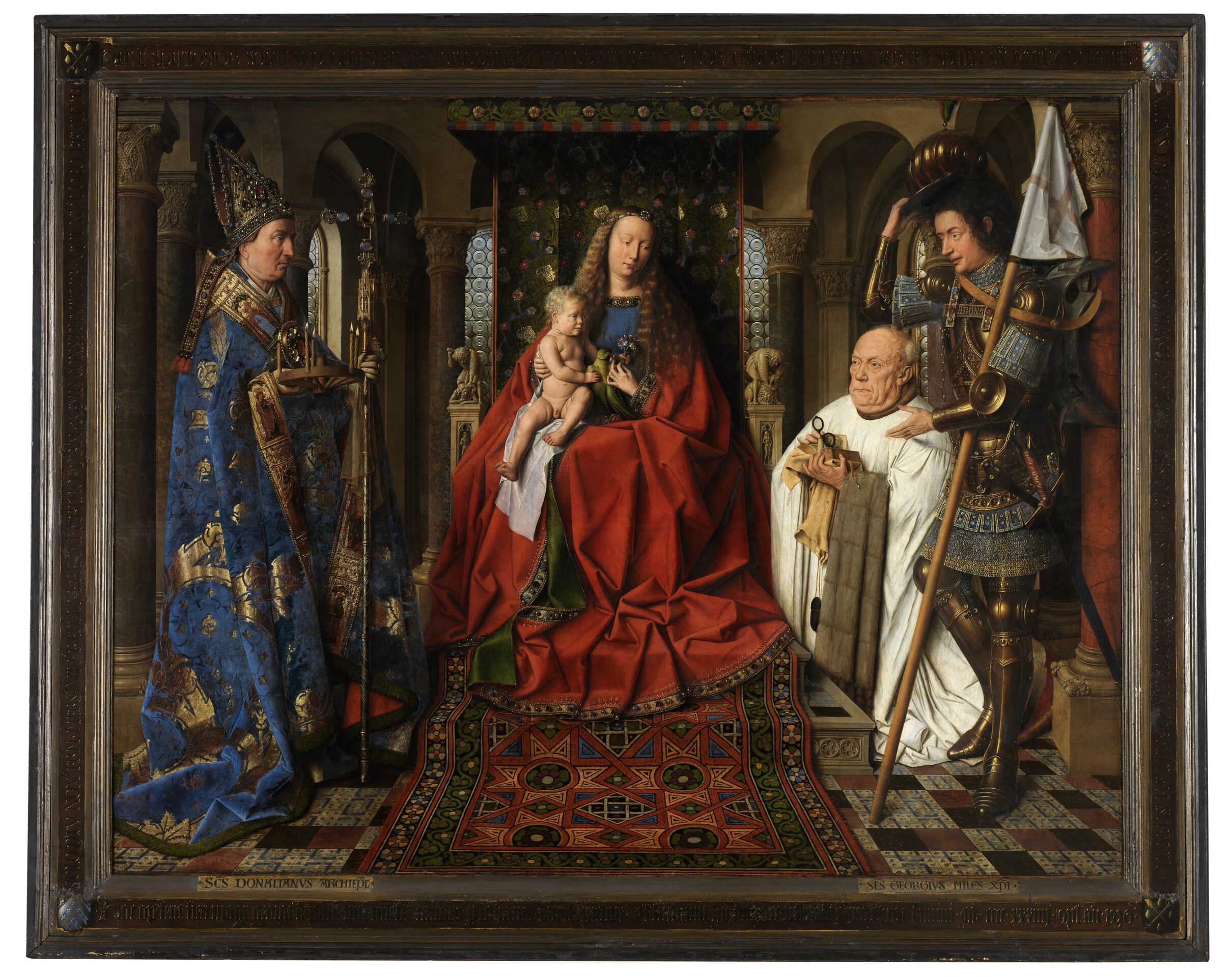

Book of Hours in art: Petrus Christus, Isabella of Portugal with Saint Elisabeth.

One manuscript, shown here with haunting clarity, records the deaths of seven children in one family – stark reminders of medieval mortality. A note from a mother, Dorothea, mourning her infant daughter, brings a human voice across six centuries. This visual evidence complements the text, showing how Books of Hours functioned not only as guides to salvation but also as registers of sorrow and hope.

Importantly, these images also illuminate the roles of women – as readers, scribes, and even illuminators. Women made up nearly a quarter of the Bruges guild’s members, and in several images, we glimpse the handiwork of female artisans, including the illuminator Kerstinekin Yweins, who ran her own workshop. Other folios show the devotional choices of female readers: saints associated with childbirth, intercessory prayers to Mary, and notes written in a woman’s hand.

Even the margins tell stories. Drolleries – comic and sometimes irreverent images of monkeys, snails or peasants – play along the edges of sacred texts, revealing a culture that embraced both solemnity and satire (see pages XX on the rabbits in medieval marginalia). These juxtapositions, visible in the pages accompanying this article, reflect a worldview in which joy and faith were not contradictions, but complements.

In a world flooded with digital content, the Books of Hours offer something defiantly tactile. Their illuminations, so vividly reproduced here, invite not just reading but looking, feeling – remembering. They are, in every sense, books to be held.