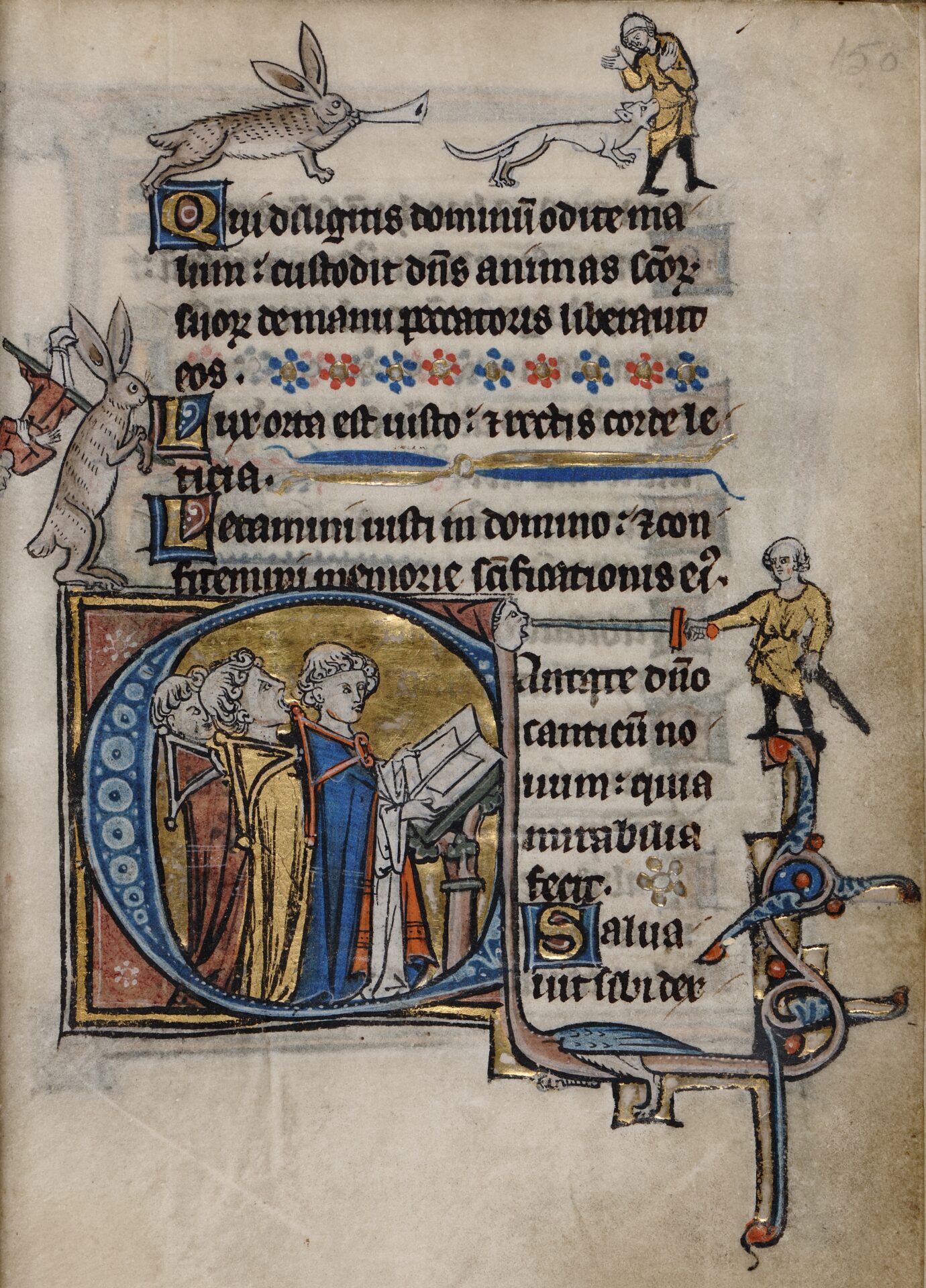

In the margins of medieval manuscripts, rabbits misbehave with glorious abandon.

These are not the meek creatures of Easter. They’re pranksters and avengers in the “world turned upside down”: the mundus inversus of the Middle Ages, where natural and social order was symbolically reversed. Hunters are hunted, clerics are mocked, and propriety is gleefully skewered.

These images are from the Peterborough Psalter and the Psalterium of Guy de Dampierre in the Royal Belgian Library, KBR. Usually found in books made for the clergy, these border illustrations – known as marginalia – could become X-rated medieval doodles. The pages become a stage for satire, not piety.

Why rabbits? In medieval symbolism, they could stand for purity or timidity, but marginal artists loved flipping expectations. In the drolleries that snake around the text, rabbits seize the upper paw – wielding axes, stringing bows, roasting hunters, even boiling their hounds. It’s a merry role-reversal, a visual quip that readers of the day would have read as comic relief and social commentary rolled into one.

In Monty Python and the Holy Grail, King Arthur and his knights fall afoul of the Killer Rabbit of Caerbannog. This was not just Pythonesque whimsy: the movie’s director, Terry Jones, had studied medieval literature at university and knew about the “bas-de-page” tradition of adding killer rabbits to manuscripts.

KBR leans into this humour. The museum’s interpretive texts invite visitors to “die of laughter,” pointing out how 15th-century borders teem with satirical scenes and animal caricatures. In this carnival zone of the page, nearly every social type is fair game, and the jokes can be as bawdy as they are sharp. The rabbiting mischief fits perfectly: a soft, familiar form used to lampoon fear, violence, or hypocrisy – a reminder that appearances deceive and hierarchies wobble.

There’s also a bookish wink. Manuscripts were costly objects – parchment devoured herds; pigments and labour cost a fortune – yet their makers still tucked in visual sniggers on the edges. That tension heightens the gag: amid sacred text and princely coats of arms, a rabbit takes aim at decorum itself. These images, from the KBR’s library of the Burgundian dukes, preserve this double register: solemn devotion centre-stage, subversive comedy in the wings.

Page after page, the rabbits keep misbehaving – not to terrify, but to remind us that even the most serious books made room for sheer, unruly fun.