A French travel magazine once listed the Wiertz Museum in Ixelles as one of the most beautiful in the world. And it is. The only problem is that almost no one knows about it. The museum is located in a forgotten corner of the city, hidden away behind the European Parliament. And it is filled with paintings that almost no one likes.

Located on a hill above Place du Luxembourg, the museum was originally built in 1851 as a studio for the Belgian romantic painter Antoine Wiertz. He chose to settle in an unfashionable location on the edge of the city, although he was convinced that the area would one day become “the centre of an immense and rich population”.

Wiertz came up with a cunning arrangement to pay for the studio. In 1850, he wrote to the Belgian interior minister offering to donate all his unsold paintings to the state if they would pay for his studio. The idealistic government agreed to the proposal, seeing Wiertz as an important artist who could enhance the identity of the young nation.

But Wiertz made sure there were some conditions attached. The museum must be free, he insisted, and the paintings had to “remain permanently fixed to the walls” for all time. The French poet Baudelaire thought it was a disastrous arrangement. “What is Brussels going to do with all that?” he grumbled. An article published in The Economist in 2009 made a similar point when it described the deal as “a masterclass in maladministration”.

Yet the government honestly believed Wiertz was special. Born in Dinant in 1806, he studied art in Antwerp, where he spent hours in cold baroque churches copying religious paintings by Rubens. The young artist then headed off to Rome in the footsteps of Rubens to paint romantic landscapes and pretty young women.

Back in Brussels, Wiertz started to work on a gigantic painting which he submitted to the Paris Salon in 1839. He hoped this would be his breakthrough, but the organisers hung it in a place where there was no hope of anyone seeing it. Wiertz never forgave the French.

Still convinced of his genius, Wiertz moved into an abandoned church in Liège where he started working on a huge painting called “The Triumph of Death”. His mother died while he was working on the canvas, which plunged him into a deep depression. But he kept on working in that gloomy church for another year. A friend finally persuaded him to move to Brussels, where he started work on another enormous painting called “The Triumph of Christ”. The foreign critics continued to attack him mercilessly. Baudelaire called him “a charlatan, idiot and thief”.

Two Girls (La Belle Rosine) painted in 1847 is probably Wiertz’s most famous painting, depicting his fascination with death and the fragility of human life.

Yet Wiertz was celebrated as a national hero when he died in 1865 and a monument was put up in his honour in Ixelles. Following his wishes, the former studio was turned into a museum, displaying more than 200 of his works – all fixed permanently to the wall, as he had instructed – along with his easel and other sentimental relics.

In the early days, Belgians would enjoy the macabre thrill of visiting the museum to look at paintings such as “Premature Burial,” in which a terrified man struggles to escape the coffin in which he is about to be buried. They also enjoyed the moral lesson of his painting “Hunger, Madness and Crime,” showing a destitute mother boiling her baby’s leg in a cooking pot. And they no doubt felt empathy for the dead man in “The Suicide,” who blew his brains out after receiving a tax demand.

In the early days, Belgians would enjoy the macabre thrill of visiting the museum to look at paintings such as “Premature Burial,” in which a terrified man struggles to escape the coffin in which he is about to be buried.

The English novelist Thomas Hardy captured the depressing mood of the place in Tess of the D’Urbervilles, where he described “the staring and ghastly attitudes of a Wiertz Museum”.

Belgian art lovers now struggle to find anything good to say about Wiertz. The museum, open limited hours, barely attracts more than a dozen visitors a day. On some days, you will be the only visitor in the vast chilly building.

Yet the huge studio is worth a look. It is a rare example of a perfectly-preserved mid-nineteenth century museum, with rooms lit by natural daylight and paintings protected by low brass rails. It would the perfect setting for a romantic film once the more gruesome paintings had been hidden from sight.

A new deal is signed

One of the most interesting details is seldom noticed by visitors. Hanging on the wall just beyond the little custodian’s office is a framed manifesto. Written by Wiertz in 1839, it is a long rambling tract that dismisses Paris as a second-rate provincial town and calls for Brussels to be recognised as the “capital of Europe”.

Most people thought that Wiertz was deranged when he wrote this. But the cluster of glass-and-steel buildings at the bottom of the hill suggest that this neglected Belgian artist was something of a visionary. The European Parliament (official address: 60 Rue Wiertz) has slowly spread through the old neighbourhood that Wiertz put on the map.

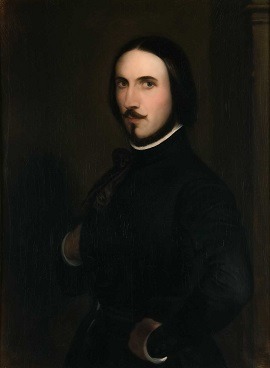

Antoine Wiertz: “Selfportrait”, ca. 1840-1845

A few months ago, the Belgian government finally got rid of its responsibility for maintaining the museum. In a controversial decision announced in October 2016, the state agreed to lease the museum and garden to the European Parliament for a token one euro. A European Parliament spokesperson said the EU institution planned to renovate the museum and use the hidden garden at the back for official events.

But the Leopold Quarter Residents’ Association immediately launched a counter-bid, offering to pay the Belgian state the sum of two euro for the museum. The local action group also launched a petition on change.org which quickly attracted almost 4,000 signatures. As well as criticising “indolent local governments” for neglecting the museum, the association attacked the plan to turn the museum into “the playground of dignitaries and their guests”.

“We want the museum to stay open to everyone,” the action group argues. “Instead of selling it to the European Parliament, we ask the Belgian state to honour the memory and will of Antoine Wiertz by opening the house to artists and ensuring the museum is more accessible.”

“To judge a painter, you have to wait at least two centuries,” Wiertz once wrote. With MEPs from across Europe now discussing the future of his museum, Wiertz might soon get the recognition he knew he deserved.