If we managed to close everything down so quickly, why can’t everything open up again as fast? That is a question most of us are wondering about... and may PowerPoints and politicians hand us their curves and their words, I propose a psychoanalytic notion that could help us make sense of our slow policymaking nowadays: the death drive.

It has little to do with physical death: your yoga session this morning, your Stephen King novel last night, your Euro game tomorrow evening and the cigarette you will be smoking during it... they all work up your death drive. A concept that has to do with relaxing – how is it connected to the relaxation of lockdown restrictions? Why is it that we anyway talk of measures needing to be relaxed, not enforced? Why did we not think about a relaxed tourism last summer, rather than a dead one?

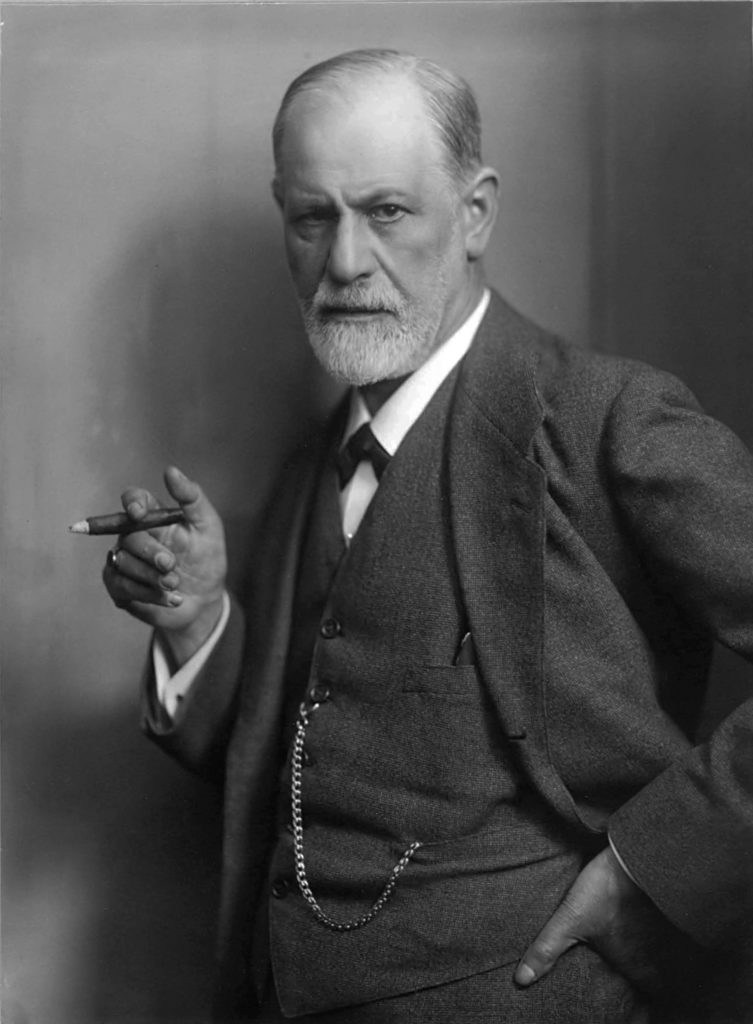

It took Freud a long time to theorize the death drive. Prior to its discovery, the psychoanalyst assumed that human behaviour always aspired for life; that we as people shall do anything, repress anything, to feel alive or to preserve our life – physical, social, political – among mankind. Freud therefore had a hard time understanding masochism, even melancholia... why are we witnessing here a lowering of the libido?

Ultimately, Freud found that the life drive must be continually grappling with its opposite; and he ascribed to that death drive an essential characteristic: a repetition-compulsion; that is, a compulsion to precisely avoid total death, to merely simulate it in loops. From here comes the mechanical, complying, almost deadlike behaviour we sometimes engage in. Aristotle defined life as movement; so the death drive is precisely that which dismisses our duty for motion; that which, so to speak, “makes everything stop.”

Think about the repetition inherent to these new variants we are hearing about – not that the virus itself has a death drive (the opposite is the case), but that the discourse around these ‘new developments’ suggest that we might return to ground zero; that all progress, all life as such, must in reverse mark “a return to an earlier state” as Freud himself characterized the death instinct.

The slowness with which we are moving to ‘return to normal’ – is it mere obedience to the numbers, or is it because of the weight of the death drive; because, geologically speaking, it is easier to roll down a cliff than to climb it back up? Our persevered reliance on facts and figures – is it not also characteristic of that death drive; for numbers themselves are not alive, themselves not inviting us to resurrect the real world?

If it is a death drive that is keeping us from living, living for real, from striking a balance between caution and recklessness, between physical health and mental health... then should we not move to a policymaking that is itself dynamic, itself alive? This would require a change of perspective: not to declaring “all this is over!” but to pledging “none of our lives have to be over!” – the walk up is difficult, but we shall get to the top so long as we are moving.

Life is movement... thus to lift all travel bans and open up all spaces, without deadening exceptions, must be a priority. Give one the freedom to move and may he himself decide to move responsibly – because as Freud knows best, it is best to be conscious of what we do, than to let the Unconscious do it for us!