As Brussels rebuilds one of its central boulevards, it preserves a relic of totalitarian worship. The capital of Europe should not celebrate Stalin’s cult — even indirectly.

On a grey autumn morning, I was walking along Avenue Stalingrad in the heart of Brussels — a city that prides itself on shaping the future of a united, democratic Europe. I stopped at a small bakery for coffee and asked the seller what he thought about the avenue’s name.

He shrugged. “It doesn’t matter, as long as business goes well.”

For him, perhaps it doesn’t. But for those of us who come from Eastern Europe, the name Stalingrad cannot pass unnoticed. It evokes the darkest chapters of the 20th century — terror, deportations, and mass repression — all wrapped in the mythology of Stalin’s cult. To see it still inscribed on the map of the EU’s capital, in 2025, feels profoundly dissonant.

A new avenue — with an old ghost

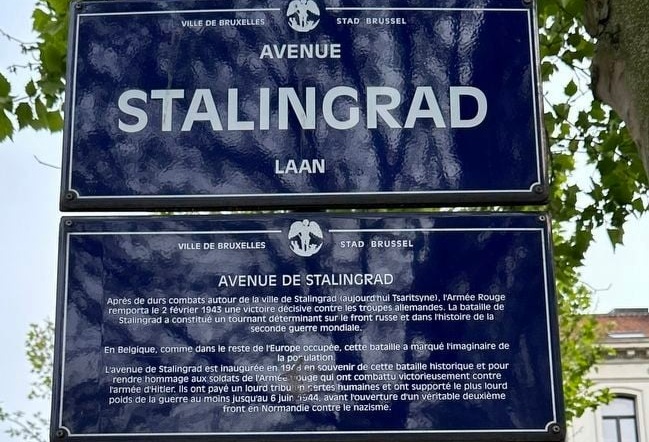

Avenue Stalingrad is currently undergoing a major transformation. The new metro station will soon open beneath it; the sidewalks are being widened, trees are being planted, and cycle lanes are being laid out. When the project is completed, it will be a showcase of sustainable, people-friendly urban design — a true “gem” in the Brussels cityscape.

Yet, amid this modernization, one thing remains untouched: the name.

It bears remembering how this name came to be. A century ago, in 1925, Stalin renamed a city on the Volga River Stalingrad — one of the many acts of self-glorification that cemented his personal cult. The title spread across the Soviet empire, appearing on maps, factories, and schools. Names, Stalin understood, shape memory. And memory, once renamed, can be controlled.

Even if Brussels’ Avenue Stalingrad was named after the Battle of Stalingrad rather than the dictator himself, the origins of that city’s name are inseparable from the regime that created it. After Stalin’s death, the Soviet Union itself recognised the moral weight of that legacy: in 1961, Stalingrad became Volgograd, and Stalino became Donetsk. Any legacy of Stalin was too much even for his Soviet successors.

The revival of a cult

Today, Donetsk is under Russian occupation — and along with the violation of Ukraine’s borders, the glorification of Stalin has crept back into the city, echoing the same cult of power that once dictated its name.

The same pattern spreads far beyond Ukraine. From Moscow to provincial Russia, Stalin’s ghost has been officially invited back — raised on pedestals, reprinted in schoolbooks, and praised on television as the embodiment of “order” and “greatness.” In this revived mythology, the Battle of Stalingrad has become a propaganda weapon — invoked to justify aggression, sacrifice, and obedience to power. Russian commentators have even compared the siege of Bakhmut to “the new Stalingrad,” cynically inverting the roles of invader and defender.

Since 2013, Volgograd has been officially renamed Stalingrad for six days each year — a symbolic sleight of hand that keeps both realities alive. It is precisely this manipulation of history, this double reality, that fuels disinformation and blurs moral boundaries.

Names matter — especially in Europe’s capital

In this light, keeping Avenue Stalingrad in Brussels is more than a historical oversight; it is a symbolic contradiction. A city that hosts the European Parliament and Commission should not normalise the legacy of a tyrant responsible for mass murder.

Imagine, for comparison, an Avenue Hitlerburg — justified because a heroic battle once took place there. The analogy is uncomfortable, but it reveals the absurdity of maintaining the status quo.

France offers a timely precedent. In June 2025, the town of Drap near Nice renamed its Boulevard Stalingrad to a local name. The Russian embassy in Paris condemned the decision, calling it “shameful and forgetful of the heroism of Soviet soldiers and the local population that rescued Europe from Nazism and fascism.” Yet Drap’s decision was not about erasing history — it was about refusing to glorify a dictator responsible for mass crimes.

Europe’s memory test

There is personal heroism in every war. We see it today in Ukraine, where soldiers and civilians alike fight to protect their country — and, ultimately, Europe’s democratic foundations — from a power that revives totalitarian habits. But Stalin’s goal was never to save Europe. If anything, he sought to dominate it — and in a sense, he partly succeeded, through the names he left behind.

The reconstruction of Avenue Stalingrad presents Brussels with an opportunity to rectify its legacy — to match its urban landscape with the values it claims to represent. To leave the name untouched would be to let Stalin’s cult linger, even if only as a shadow beneath new paving stones.

A final thought

An old joke goes:

A tour of Hell. The guide is asked: “Why is Hitler standing in filth up to his neck, and Stalin only up to his waist?”

“Because Stalin climbed onto Lenin’s shoulders.”

Brussels has the chance to step off those shoulders — and finally, to stand on its own.