After the Brussels attacks last year, it became commonplace to blame the bombings on systemic failures within Belgium, including what some claimed was a culture of corruption. Belgium, they said, had become a breeding ground for radical jihadism thanks to a catalogue of problems, not least corruption and nepotism in public service, which undermined confidence in the police and the judicial system. But is corruption really gnawing at the fabric of public life, and turning Belgium into a failed state?

Most experts say no. From international organisations to NGOs and legal scholars, the studied verdict is that Belgium is doing much like most other rich, European countries in stamping out corruption.

Surveys show corruption is rare and is not an obstacle for doing business in Belgium: there is a well-developed legal and institutional framework, with the Criminal Code criminalising both public and private bribery, passive and active bribery, and bribery of national and foreign public officials.

But there are areas that could be improved, from whistle-blower protection to the allocation of adequate resources for anti-corruption efforts. In January, Belgium was criticised in a report by the Council of Europe’s Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) for failing to properly implement or address any of its 15 recommendations, including rules over lobbyists seeking to influence the parliamentary process.

It came after the OECD’s Working Group on Bribery slammed Belgium’s “limited efforts” to comply with its Anti-Bribery Convention, saying the government was not doing enough to fight against the bribery of foreign public officials, evidenced in part by the lack of resources committed to investigations, prosecutions and sentencing in these cases.

Like in many areas, when it comes to corruption, Belgium is a middling country. Transparency International ranked Belgium as the 15th cleanest nation out of 176 countries in its 2016 Corruption Perceptions Index, down from 19th in 2011, and its all-time high of 29th in 1999. It said that the judiciary is independent and the administration is predictable and reliable, despite complaints concerning cumbersome procedures and unnecessary red tape, nepotism and favouritism sometimes found within public service companies.

The Index said real estate and construction industries are the areas where corruption (more specifically, money laundering) crimes are most likely to occur, and public procurement is the sector most susceptible. But the Transparency International report also offered a few suggestions, including dedicating more resources to enforcement authorities and the courts, and giving higher priority to the investigation and prosecution of foreign bribery offences.

Similarly, a 2014 European Commission report grumbled that proactive anti-corruption policy was often only implemented in response to a major corruption case, like the city of Antwerp after finding local officials had used their professional credit cards for personal purchases. Its own suggestions include:

- ensuring that ethical rules and tools to prevent conflict of interest are implemented for all appointed and elected officials at all levels;

- increasing the capacity of the justice system and law enforcement to avoid that corruption cases are not prosecuted due to expiry of the statute of limitations;

- tighter rules on party funding.

Corruption prevention efforts greatly vary between the country's regional governments. Flemish anti-corruption policies are more developed than in Wallonia. A 2013 Gothenburg University study that measured citizen perceptions about corruption, ‘From Åland to Ankara: European Quality of Government Index’ ranked Flanders 59th and Wallonia 133rd.

The current government under Prime Minister Charles Michel says the fight against corruption is a priority, and enshrined it in the 2016-2019 National Security Plan aimed at raising awareness among companies doing business in international markets for goods and services, by warning them of the many risks and their consequences.

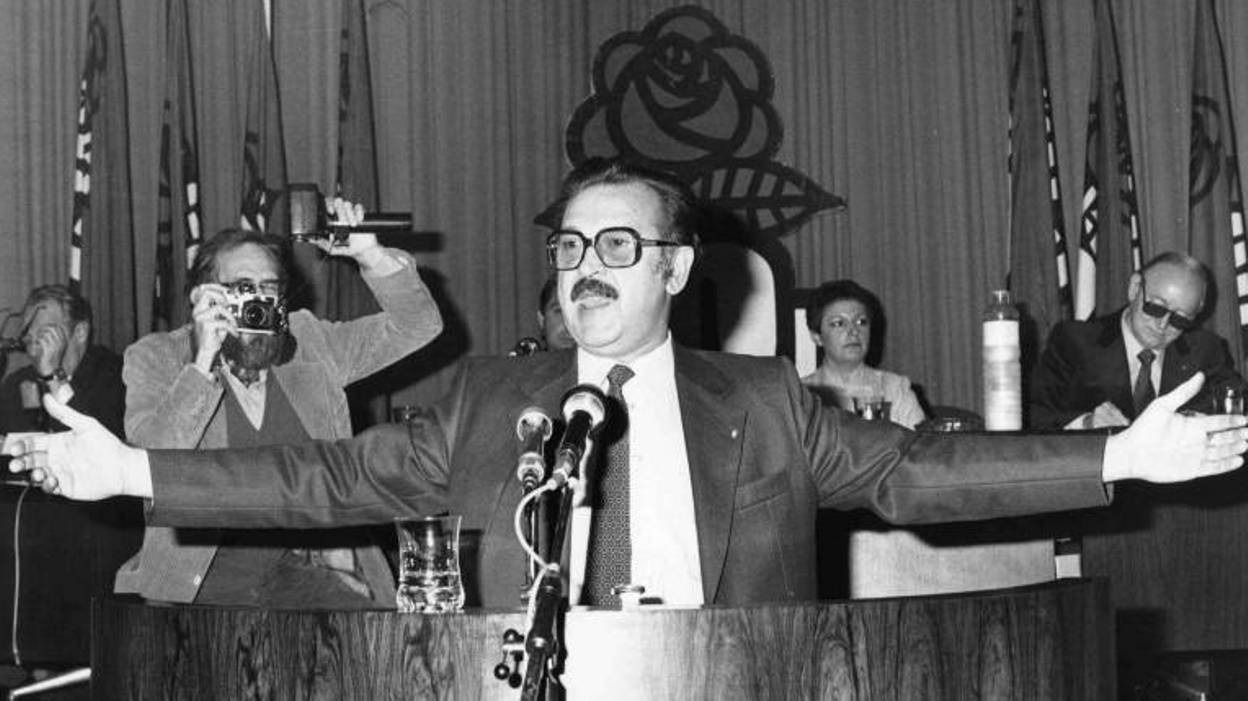

Former Deputy Prime Minister André Cools was gunned down in 1991 by gangsters, seemingly on the orders from within his Socialist party in Wallonia. The murder was linked to a big corruption scandal, known as the “Agusta scandal” which involved bribes paid to several Belgian politicians by aviation firm Agusta in order to secure a 1988 order of army helicopters.

Part of the existing structure was put in place after a series of scandals in the 1990s that exposed a well of political sleaze. Former Deputy Prime Minister André Cools was gunned down in 1991 by gangsters, seemingly on the orders from within his Socialist party in Wallonia. It was linked to the bribes that aviation firm Agusta paid ministers and officials to secure a 1988 order of army helicopters: the scandal led to the conviction of top members of the Walloon and Flemish Socialist parties, including then-NATO head Willy Claes. And when the Marc Dutroux child sex scandal erupted in 1996, it produced a torrent of public outrage over the apparent protection he enjoyed from local political figures in the Charleroi region, as well as Belgium's Italian Mafia gangs.

In the aftermath of the Dutroux scandal, hundreds of thousands of Belgians marched the streets expressing outrage at what was seen as corruption and mismanagement in the juridical system.

At a December 2013 event hosted by the Re-Bel initiative, Antonio Estache, Jeroen Maesschalck and François Vincke said that Belgium contained many conditions that typically encourage corruption. These include: strong internal cultural differences; strong decentralization built into the constitution, religious traditions that discourage challenges to authority; and hierarchical enforcement rather than procedural tradition.

The speakers accepted the evidence for Belgium’s middling score on corruption, but pointed to perceptions that were somewhat more cynical. For example, a 2012 Ernst and Young study showed 42% of 50 Belgian-based firms considered paying bribes is acceptable in times of crisis to get contracts (against 26% in the global sample).

This tolerance for corruption is confirmed by a 2012 Eurobarometer survey, that suggests that 71% of Belgians thinks corruption is a problem at all levels of government, and about 67% think it is part of the business culture (below the EU average of 76 %). About half believe that it is a problem for public tenders and building permits, 40% for construction, food, health and sanitary inspectors, and about a third see it as a problem to obtain business permits.

While this matches other European countries, what stands out is the reason Belgians think corruption is a problem; that authorities are not trying hard enough to deal with it and, most importantly, that there is some degree of fatalism in the way the problem is treated. The Eurobarometer data shows that 83% of Belgians agree that corruption is unavoidable, compared with 70% for the EU.

All this suggests that while corruption in Belgium is more or less what might be expected from a European country, it feels worse because of other factors, like the weak national identity, and cynicism about government and bureaucracy.