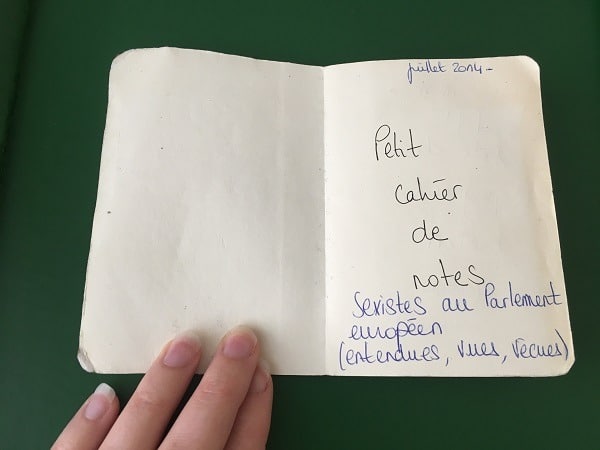

Stored away in a European Parliament office cabinet is a small, flower-patterned notebook. The pages contain anonymous entries – handwritten notes detailing an array of disturbing experiences within the institution, the majority of which have never been spoken of or heard by anyone else before. This book is called the Petit cahier de notes sexistes.

A clamour of voices tremble from the pages, the lamentations of the victims – those who had previously been silenced for fear of reprisal or scrutiny. Here, amongst the time-eroded records, their songs of tragedy are heard in a terrifying clarity. The book contains the very first accounts of sexual harassment in the European Parliament.

In 2014, an intelligent and sprightly 24-year old French woman arrived at the doors of the Parliament’s imposing Altiero Spinelli building. Her name is Jeanne Ponté, and, following years of intense study in the field of European law, she came to Brussels to embark on a career, which she hoped would allow her to contribute to the ideals of the European project and espouse the wider virtues of the union.

“I thought that as the house of representatives for EU citizens and women, people would be more open-minded and understanding here,” Jeanne tells me. Her words are muscle-tight and firm – she speaks with a resolve completely void of any self-pity.

When Jeanne started working at the Parliament, many instances of everyday harassment, be they inappropriate comments, touching, psychological manipulation or offers of sexual bribery, were accepted as run of the mill practices. Things to be endured, almost as terms of employment.

“Women would offer advice to one another about who to avoid in the elevators, ‘be careful with that guy if you are alone together in the corridor, have someone around with you when you’re with him,’ they told me when I first arrived.”

Face-to-face with harassment

Ten days into her new role as a Parliamentary assistant in Brussels, Jeanne was subjected to an experience that would bear the stimulus for the creation of the Petit cahier.

A group of industry lobbyists had congregated directly in front of the European Parliament, for a networking event. Jeanne, along with two of her colleagues, attended.

“I saw this old guy, standing at the corner of the group,” Jeanne recalls. She averts her gaze from mine and crosses her arms – it’s an uneasy memory to revisit. “His eyes were crawling all over me, he stared at me for quite some time. I became uncomfortable and I tried to leave the area, to get away from him. He started to follow me.”

“As I attempted to leave, he blocked my way with his arm across my chest. ‘Are you new here? I haven’t seen you before. Let’s go for a beer or a coffee after work,’ he said.”

During this display, there was a large group of political officials and parliamentary staff in the area. The man in question, Jeanne told me, exhibited an arrogance indicative of a sense of immunity that MEPs feel to do as they please, and to whomever.

“I thought, ‘I don’t want this to be a part of my working life.” Jeanne says. As a means to wrestle with such day-to-day incidents of sexual harassment, she started writing down her experiences in a small, inconspicuous notebook. After a while, others got wind of her practice.

Jeanne’s “Petit cahier”, detailing first accounts of sexual harassment in the European Parliament, has led to the establishment of the #MeTooEP movement inside the European Parliament as well as a resolution on combating sexual harassment.

Those that came first were other victims – they came to contribute. “The book became a place for solidarity because the women were from different political colours, different nationalities, different ages, different work contracts,” Jeanne says. “They all came to me and shared their stories.”

However, as the Petit cahier gained repute within the mirrored walls of the European Parliament, there were those who sought out the book for altogether ulterior motives. “People were entering my office without me being there. They were trying to find the notebook to obtain information about the incidents.”

“I’m not sure for what reason. I eventually decided to take the notebook home.”

Awareness begins

And it wasn’t only within the Parliament that the Petit cahier started to cultivate interest. When the MEP she works for, Edouard Martin, was called onto a French radio station to talk about sexist comments made by a member of the French government in October 2017, he cited Jeanne’s book. Soon after, she found herself pasted across headlines all over the continent.

The result of this spike in publicity for Jeanne’s Petit cahier? A substantial increase in victims coming forward, which subsequently led to the establishment of the #MeToo movement in the European Parliament. A small group of MEPs wielded the political baton of the cause, including Malin Björk, Édouard Martin, Terry Reinke and Angelica Mlinar.

The undertaking gave rise to the adoption of a resolution on combating sexual harassment, but, thus far, not enough has been done to implement the measures outlined in the text. One such area, Jeanne says, is the mandatory enforcement of sexual harassment training for all Parliament staff. Currently, it’s obligatory for all administrative staff to take part in workshops on the subject, but MEPs are not required to do so – reifying their sense of exemption from wider workplace guidelines.

As the movement gained prominence and the pages of the Petit cahier filled up fast, a greater challenge was also assumed: to provide a larger and more accessible platform for the testaments. The MeTooEP online blog was launched. To this day, entries continue to be submitted, detailing the examples of everyday sexism at Parliament. Jeanne hopes the blog will continue well into the next mandate and beyond.

The struggle goes on

Fortunately for some, the forces of populism did not overwhelm the recent European Parliamentary elections as many had thought they would have done. Rather, the EU witnessed a fracturing of its dominant poles on the centre-right and left, resulting in an increase in popularity for liberal and green, as well as Eurosceptic outfits.

Nonetheless, Jeanne remains concerned that a Parliamentary composition made up of around 60% of new members may diminish the prominence of the #MeToo campaign.

“We rely on progressive political forces,” she says. “They tend to make more space for victims to speak out. We hope that the progressive voice will not be lessened going into the new mandate.”

“The resistance could be harder,” she adds, a pace in her voice and a look of concern etched across her face. “We won’t be surprised if there is a backlash to our movement. We may lose some of the support we have built up.”

In a bitter twist of fate, one person who won’t be returning to Brussels after the elections is Jeanne herself. She is not however ceding the fight against sexual harassment. “I will take some much-needed time off,” Jeanne tells me. “I will still be active inside the movement. It’s what I created, so I will not let it go.”

She sighs and twists a curl in her hair. “Politics is a hard world for women,” she adds. “They suffer.”

For the incoming MEPs, however, Jeanne has two unambiguous messages. One: We are here to care for you and Two: We are watching you.

“The biggest challenges we have? We need more men to support our cause. We need a broader coalition of political support, from all over Europe,” she says. A steely determination negotiates itself to the forefronts of her eyes:

“It’s time to take these stories outside of the European Parliament.”