Facebook’s reaction to the military coup in Myanmar gives the social media platform the chance to reconsider its policies in the southeast Asia region, notably in Cambodia.

The social media platform responded to the Myanmar coup by saying that it is treating the situation as an “emergency.” Facebook is “reducing the distribution of content that likely violates our hate speech and incitement policies, as well as content that praises or supports post-election violence including a coup.”

The coup in Myanmar has attracted greater media attention than the ongoing crackdown in Cambodia, where life under a brutal dictatorship is a daily reality. Prime Minister Hun Sen ordered the supreme court dissolution of the peaceful opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), which was carried out in November 2017. Supporters of the CNRP and other critics of his regime have been relentlessly beaten up and arrested ever since as Hun Sen tries to eradicate the party at grassroots level.

Facebook says in its community standards that it wants people “to be able to talk openly about the issues that matter to them, even if some may disagree or find them objectionable . . . We expect that people will respect the dignity of others and not harass or degrade others.”

These conditions are far from being met in Cambodia. Sam Sokha, a garment worker and mother of three, threw her shoe at a ruling party street banner in 2017. The footage was shared on Facebook and she fled to Thailand as police sought to arrest her. The Thai authorities arrested her and sent her back to Cambodia, where she was sentenced to four years in prison. This was despite an apology from Sam Sokha to Hun Sen.

In January 2019, Kong Mas, a CNRP supporter in Svay Rieng province, was arrested for criticising the government on Facebook over its handling of talks over the European Union’s Everything But Arms (EBA) scheme, which allowed duty-free access for Cambodian exports. The government warned the public not to use “inappropriate words and negative visions” which could create “confusion” over EBA.

“It is Hun Sen who deprived citizens of a democracy. It is the regime of Hun Sen that destroys forests,” wrote Kong Mas, who is a father. He was given 18 months in prison. Cambodia has since partially lost its EBA access due to its dreadful human rights record.

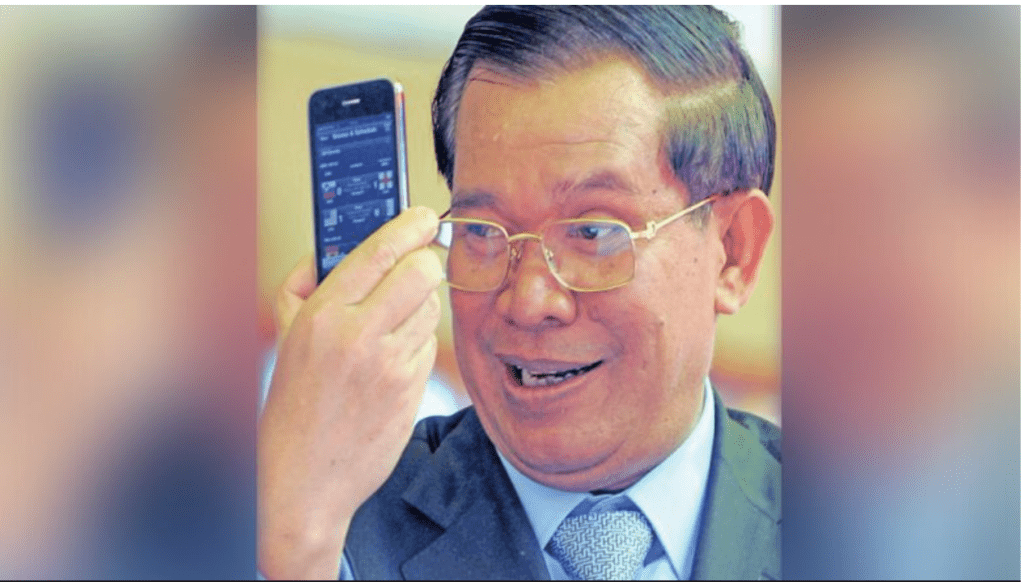

In July 2019, Hun Sen said that any former opposition party member could face arrest for insulting him on Facebook. His aggression extends to his Facebook critics abroad. “You are outside the country, but your property is inside the country. I will confiscate all of it, only when the court rules that I am the winner of the case. This is a message for you,” he said in March 2019. Cambodia’s courts, of course, are under Hun Sen’s political control.

Click Farms

Hun Sen has used click farms in places like the Philippines and India, where the Khmer language is not even spoken, to build a mirage of popularity on Facebook. He keeps his page moving by posting music videos and ordering ruling party officials to share them. His intimidation of dissenting Facebook users occurs in a context where traditional television and print media are firmly under his control. Social media is the only public outlet where dissenting voices can be heard.

The lesson from the mass protests which have followed the coup in Myanmar underlines that given by the pro-reform protests in Thailand. People in southeast Asia have an aspiration for democratic politics that can never be erased. The personal dictatorship of Hun Sen is unable to respond to that aspiration other than through violence and intimidation. His day of reckoning could come at any time.

Increasing Internet penetration creates the danger for Hun Sen that traditional censorship will become ineffective as people turn to online sources for information and opinions unavailable elsewhere. In 2020, Internet penetration in Cambodia reached 48%, versus 39% in 2015.

Facebook has yet to fully understand the implications of this increase, which will continue each year.

The platform has the chance to become a main forum of public discussion in countries subject to mainstream media censorship. Yet that will be impossible if public leaders who bully and intimidate others are allowed to keep posting. Ignoring the problem would mean that Facebook will be seen by many as a tool for dictators. Hun Sen has violated Facebook’s rules on numerous occasions and his page should be suspended and if necessary banned.

By Sam Rainsy, co-founder and interim leader of the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP)