Britain has never been an enthusiastic member of the European Union – and soon it could be the first to leave. With a referendum expected as early as June, the In and Out camps are neck and neck in the polls. Betting markets put the chances of British exit, or Brexit, at around a third. But I reckon the odds are more like fifty-fifty. And with the crisis-ridden EU already unravelling at an alarming rate, Brexit could cause it to disintegrate even further.

The immediate focus in Brussels is on Britain’s renegotiation of its EU membership. The good news is that a deal is doable, with luck at the summit of EU leaders on 18-19 February. Prime Minister David Cameron wants to keep Britain in the EU – and so do other EU leaders, for a variety of reasons. Liberals appreciate the UK’s generally outward-looking, pro-market views. Even statists value its defence and foreign-policy clout. Almost everyone is glad that it dilutes German dominance. Even its scepticism of poorly thought out grand EU visions can be helpful. Above all, losing the EU’s second-biggest economy – and a member with a UN Security Council seat – would diminish the EU’s global standing and set a terrible precedent.

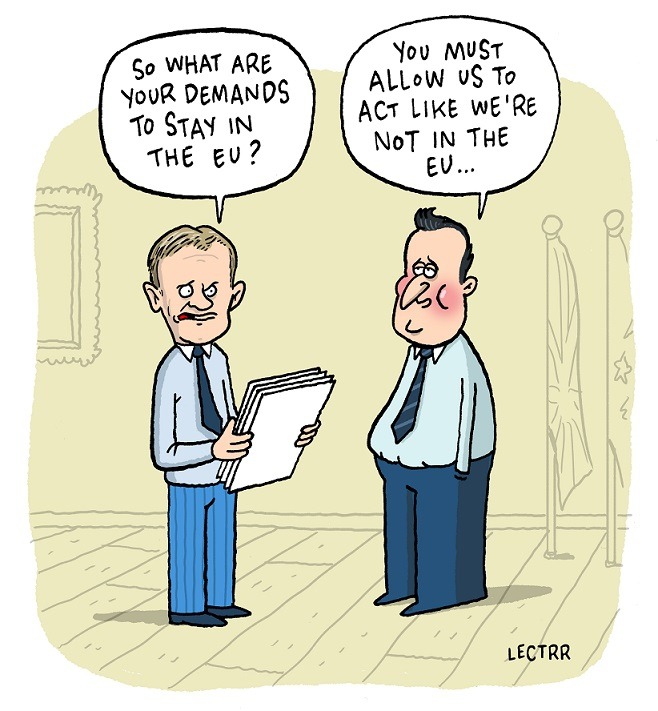

Cameron’s counterparts want Britain to stay – but not at any price. He has tailored his demands accordingly. He is seeking relatively modest changes in four areas: business competitiveness, sovereignty, safeguards for non-euro members and migration. With flexibility on all sides, much of this is achievable.

On business competitiveness, Cameron’s call for the EU to advance the single market, seek foreign trade deals and scrap unduly burdensome regulation goes with the grain of thinking in Brussels. On sovereignty, he is seeking confirmation that the EU Treaty commitment to “ever closer union” is not binding on Britain. Since the UK has permanent opt-outs from the euro and much else, it clearly isn’t; putting that down in writing shouldn’t be too difficult. Cameron also wants to enhance the power of groups of national parliaments to object to unwanted EU legislation. This is probably achievable too, so long as it stops short of giving them an outright veto.

Cameron’s most important demand concerns protecting the interests of non-euro members. Those nine countries can now be outvoted, not least on vital single-market issues, by the 19 euro members, who together form a qualified majority. So far this hasn’t happened, not least because countries such as Germany and Greece hardly see eye to eye. But if the eurozone were to integrate further and create more common institutions, this would certainly be a genuine concern.

EU leaders will doubtless agree to confirm that nothing the eurozone does should damage the single market and that Britain won’t be forced to contribute to future eurozone bailouts. An additional concession would be a double-majority voting system requiring the consent of both euro and non-euro members, like the one adopted during the creation of the eurozone’s banking union. Another would be a form of emergency brake that stops short of an actual veto.

The most controversial issue is migration. Cameron is seeking to deny EU migrants access to in-work benefits for four years. This seemed like a non-starter, since it would discriminate against EU citizens and disproportionately harm people from countries such as Poland. But with EU governments reeling from the refugee crisis and under attack from increasingly popular xenophobic parties such as Marine Le Pen’s “Front National” in France and Germany’s “Alternative für Deutschland”, longstanding principles suddenly seem more bendable. So a solution may be found after all.

The details of the renegotiation deal are unlikely to sway many British voters, who aren’t obsessed with the minutiae of safeguards for non-euro members. But the agreement is still important. A February deal would allow the referendum to take place in June, before the expected peak of summer refugee arrivals. Polls also suggest that Cameron’s endorsement of staying in a “reformed EU” could win over wavering Conservative voters. Above all, a deal would free Cameron to start campaigning on the broader case for Britain to stay in the EU.

A solid case can be made that Britain enjoys the best of both worlds. It is inside the EU, with full access to the single market and an important say in setting its rules, but outside the dysfunctional and mismanaged eurozone and relatively isolated from the chaos of a collapsing Schengen area and the EU’s ineffective attempts at a common asylum policy. Cameron will argue that EU membership enhances Britain’s economic and national security.

But referendums tend to be decided by emotion, not reason. For instance, the case for EU cooperation in combating cross-border terrorism seems self-evident, yet only last December, after the Paris attacks, Danes rejected closer police cooperation with the EU in a referendum dominated by fears about refugees and terrorism. And in the Brexit referendum, the Out campaign’s pitch is beguiling – freedom from Brussels, regaining control over Britain’s destiny – whereas the In camp is tarred by the reality of the EU, warts and all.

The referendum on Scottish independence in 2014 is a warning. Scotland is hardly an oppressed colony, yet the Scottish National Party managed to convince many angry Scots that all their problems were due to remote politicians in London, for which the solution was a blank slate called independence. Scaremongering by the Unionist camp about the potential consequences of independence failed to prove decisive. When a poll suggested the pro-independence camp would win, UK politicians scrambled at the last minute to bribe Scots to remain in Britain with promises of extra devolved powers.

At a time of anti-establishment rage and EU crisis, the Out camp’s strategy of blaming everything that people dislike about their life and modern Britain on Brussels bureaucrats and EU migration has obvious appeal. Out voters can then project their personal ideal country on to a post-EU future. Free-marketeers fantasise about a global, liberal Britain stripped free of regulation. Leftists dream of building socialism in one country. Xenophobes and reactionaries have visions of pulling up the drawbridge, turning the clock back to the 1950s, and stamping on difference.

Since few Britons have a heartfelt connection to the EU, the In camp’s main emotional card is fear: of an uncertain future outside the EU and the economic cost and political isolation that this may entail. But while most voters are risk-averse, such scaremongering may not work, not least because the EU’s future seems so uncertain at the moment in any case. Nor do fears of a loss of influence for British officials necessarily resonate with voters. Wheeling out business leaders and financiers to make the case for EU membership may repel as many voters as it convinces. And the EU is too unwieldy for it to make last-minute concessions to win over sceptics.

It is complacent to assume that the status-quo option of remaining in the EU will inevitably triumph. The risk of Brexit is very real. And if Britain votes to leave, other Europeans are likely to demand a referendum too. Marine Le Pen is ready to pounce.

By Philippe Legrain