If Vladimir Putin decided to invade the European Union, Russian tanks could be in Brussels within 48 hours. The heavily militarised Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, which is squeezed between Lithuania and Poland, is a mere 600 km from Berlin. And from Germany’s capital to the EU’s is only another 765 km.

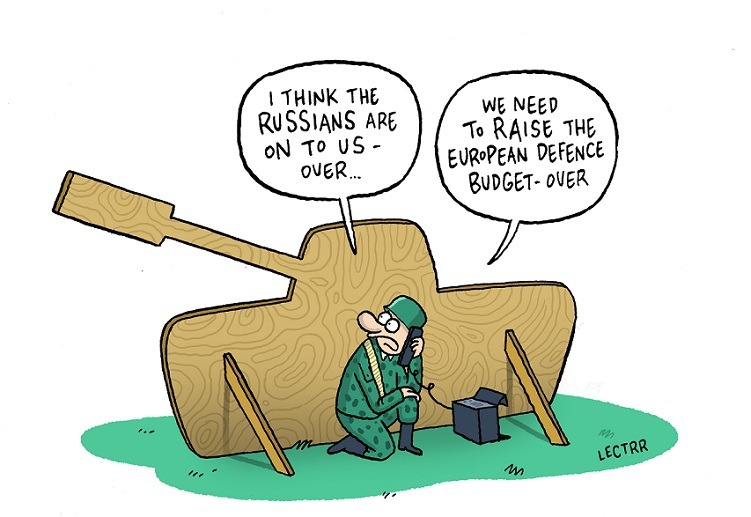

A surprise attack would likely encounter little resistance. Germany’s armed forces are so depleted that it has planes that don’t fly, tanks that don’t drive and submarines that don’t sail. As for Belgium, more than a third of its puny defence budget goes on pensions. The EU itself has no army at all. The siege of the Berlaymont would doubtless be over sooner than you can say “we surrender”.

Such a scenario may seem far-fetched. And my point is not that such an invasion is imminent. But is it really inconceivable? Would you bet Europe’s future that it couldn’t ever happen? And shouldn’t Europe be doing more to defend itself against a whole host of threats?

Until recently, one could suggest at least three reasons why Russia would never invade Europe. Russia wasn’t a threat. American nuclear weapons would deter any potential aggression. And in any case, war didn’t happen in Europe any more. Yet all three of those reasons now look much less robust than before.

For a start, Russia certainly is a threat. President Putin feels aggrieved by Russia’s diminished stature since the end of the Cold War. The break-up of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact enabled eastern Europe to escape Moscow’s writ. That ten of those sovereign states have since democratically chosen to join the EU is seen as impudence on their part and as a power grab by the EU.

While Putin’s animosity towards those he feels belong in Russia’s sphere of influence is particularly great, he also resents the EU itself. By clubbing together in the EU, European states can resist Russian bullying and even impose collective sanctions against the Kremlin. Soviet leaders once eyeballed American presidents as equals; now mighty Gazprom, a state-owned company that enjoys a monopoly on Russia’s gas exports, must bow before a woman from tiny Denmark: the EU’s competition commissioner, Margrethe Vestager.

Whipping up Russian nationalism and anti-European sentiment is also a convenient distraction from domestic discontent at the corruption, brutality and economic mismanagement of Putin’s regime. So too is military aggression. Russian forces invaded Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014. In 2015, they intervened to prop up Bashar al-Assad’s barbarous regime in Syria. An added bonus from Putin’s perspective is that this displaced many refugees, destabilising European governments.

Make no mistake: Russia poses a direct threat to the EU. Its illegal annexation of the Ukrainian province of Crimea in 2014 – the first forcible redrawing of a frontier in Europe since the Second World War – is a grave challenge to the EU’s belief that international relations should be governed by the rule of law.

Russian supported forces killed 298 civilians, most of them Dutch, when they shot down Malaysia Airlines flight 17 over Ukraine. Putin’s henchmen tried to sway the recent French and German elections by stirring up lies and hate and promoting pro-Russian far-right and far-left politicians. Its spies have used chemical weapons to assassinate people on British soil. And its fighter planes regularly invade Swedish airspace and its submarines Swedish waters. So alarmed are the Swedes that they are bringing back military conscription.

Europe can no longer take American support for granted

The Russian threat would be less alarming if the United States was fully committed to Europe’s defence. But President Donald Trump isn’t. He resents the fact that Europeans spend much less on the military than Americans do. He has called the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) – which commits the US, Canada and their European allies to come to each other’s defence if attacked – “obsolete” and has threatened to “go it alone”.

He has even designated the EU as America’s greatest “foe”. It is little comfort that Trump’s main reason for seeing the EU as an enemy is its huge trade surplus with the US. After all, he explicitly seeks to use America’s security guarantee as leverage in trade disputes.

Trump meeting European leaders at the most recent NATO summit held in Brussels in July.

For sure, Trump is erratic. A lot of what he says is bluster. Having threatened North Korea with nuclear annihilation, he now professes to be best buddies with its dictator, Kim Jong Un. And he hasn’t pulled the US out of NATO – and indeed can’t do so without the approval of the US Senate.

But ultimately it is the president who would decide how the US would respond to a Russian attack on Europe, or the threat of one. And American support can no longer be taken for granted.

In her typically low-key style, Angela Merkel captured it well. “The times in which we could completely depend on others are on the way out,” the German Chancellor observed last year.

But what are Europeans going to do about it? It is complacent to believe that war in Europe is unthinkable. For sure, the EU is an amazing achievement. Neighbours who used to settle their differences on the battlefield now do so through bleary-eyed haggling in overnight European Council meetings.

But there is a dangerous tendency for pride in the EU way of doing things to shade into arrogance and wishful thinking: that the rest of the world ought to operate according to EU norms – and that if others don’t, the EU still ought to act as if they do so until they realise the error of their ways.

There is much to be said for managing international relations through peaceful negotiations and multilateral institutions. But in the face of violence, force – or the threat of it – is often needed to restore order. When war broke out in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, European diplomacy was powerless to stop it; American military muscle was also needed.

Can Europe defend itself?

Now that Europe can no longer count on America to defend it, it needs to be able to defend itself. While Trump is obnoxious, he is right that Europeans don’t spend enough on their defence. The post-Cold-War peace dividend was welcome; it isn’t a birthright.

To point out, as some in Germany do, that Germans spend more on development aid than Americans do is scarcely pertinent; how does that deter Russian tanks? Such soft power is not a substitute for hard power; it’s a complement to it.

Europe doesn’t just need to spend more on defence; it needs to do so more effectively. While European NATO members together spend around four times what Russia does on defence, they get much less bang for their euro. All too often governments cosset national champions in the defence industry. Instead there needs to be much more joint development and collective purchasing of expensive military hardware.

Since some EU countries are officially neutral and others are reticent about closer cooperation on defence, closer integration needs to proceed more rapidly among coalitions of the willing, as France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, has rightly suggested. But the EU’s recent defence initiative, known as Permanent Structured Co-operation (PESCO), is unambitious and unwieldy.

The crux of the problem is that only two European countries – France and Britain – have a heavy-weight army with a nuclear deterrent, and one of them is soon due to leave the EU. So while there are practical hurdles to security cooperation with a non-EU state, it would be foolish not to keep Britain involved in European defence efforts.

So it is good that President Macron’s new European Intervention Initiative includes Britain and eight other countries. Its purpose, he says, is to build a “common strategic culture”, as part of a broader effort to “ensure Europe’s autonomous operating capabilities, in complement to NATO.”

Trickier still, there needs to be a debate in Germany and elsewhere about developing a national – or better still, a European – nuclear deterrent.

Defending Europe’s borders is vital. So too is combating insidious threats such as cross-border terrorism and state-sponsored cyberattacks that could cripple vital infrastructure. But perhaps the most alarming security threat to the EU comes from within.

Putin now has allies in the Italian, Austrian, Hungarian and Greek governments. There are photos of Austria’s foreign minister Karin Kneissl, who was appointed by the pro-Russian far-right Freedom Party, dancing with Putin at her recent wedding. Other Kremlin allies include Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France, and the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Die Linke in Germany.

Putin may not need to invade the EU to destroy it; his allies may destroy it from within.