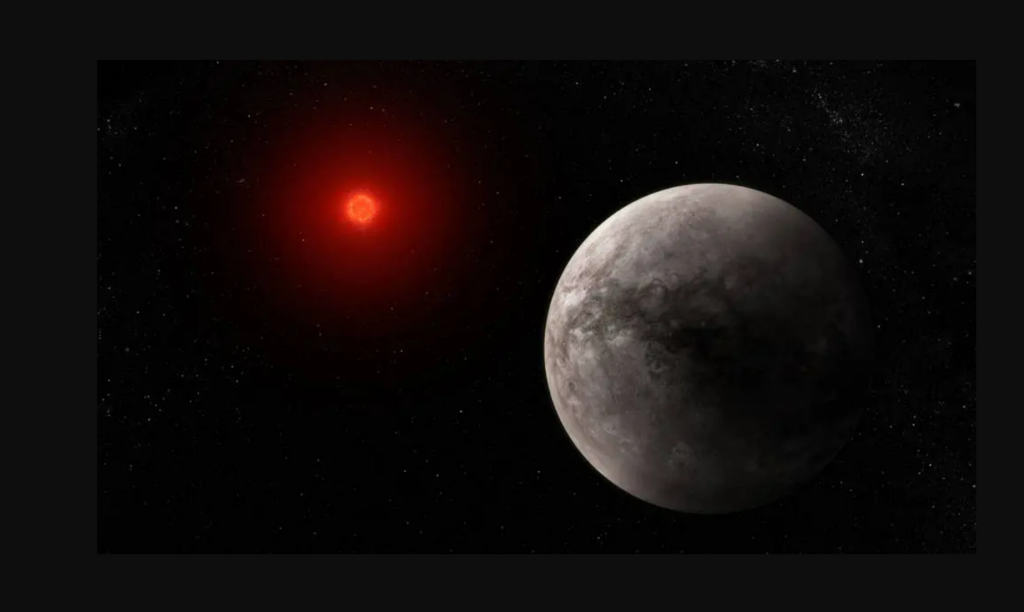

The "Belgian" exoplanet TRAPPIST-1b – some 39.5 light years from Earth and outside our own solar system – is too hot to be inhabitable and likely does not have a significant atmosphere, new data collected by the James Webb telescope suggests.

An international team of researchers used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to measure the temperature of the rocky exoplanet TRAPPIST-1b, based on its thermal emission: heat energy given off in the form of infrared light detected by Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). They found that the planet’s daytime temperature is over 500 Kelvin (232 °C) and it has no significant atmosphere.

"These observations really take advantage of Webb’s mid-infrared capability," said Thomas Greene, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Ames Research Center and the study's lead author. "No previous telescopes have had the sensitivity to measure such dim mid-infrared light."

This is the first detection of any form of light emitted by an exoplanet as small and as cool as the rocky planets in our solar system, marking an important step in determining whether planets orbiting small active stars (like TRAPPIST-1) can sustain atmospheres needed to support life. It also bodes well for Webb's ability to characterise temperate, Earth-sized exoplanets using MIRI.

Why is TRAPPIST-1b called a 'Belgian' exoplanet?

Belgian astronomer Michaël Gillon from the University of Liège made a major contribution to the discovery of exoplanets through his use of the TRAnsiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope ("TRAPPIST") in Chile.

The name was also given to the star around which the seven planets orbited – a clear nod to Belgium's beer culture, Gillon later revealed. The exoplanets were given the name of their star, with the letters b to h as extensions.

Belgian astronomer Michael Gillon poses with his trophy after winning the Walloon of the Year 2021 prize in Namur. Credit: Belga/Maxime Asselberghs

In early 2017, astronomers reported the discovery of seven "Earth-like" rocky planets orbiting an ultracool red dwarf star (or M dwarf), 40 light-years from Earth. Although they all orbit much closer to their star than any of our planets orbit the Sun, the star is relatively small so they receive comparable amounts of energy as our planets from the Sun.

It was the first time that so many Earth-like planets were discovered around just one star. Their distance from the star raised the possibility that they contain liquid water and might even host alien life.

TRAPPIST-1b, the innermost planet, has an orbital distance about one hundredth that of Earth's and receives about four times the amount of energy that Earth gets from the Sun. While not within the system’s habitable zone, observations of the planet can provide important information about its sibling planets, as well as those of other M-dwarf systems.

No atmosphere

"There are ten times as many of these stars in the Milky Way as there are stars like the Sun, and they are twice as likely to have rocky planets as stars like the Sun," said Greene. "But they are also very active – they are very bright when they’re young, and they give off flares and X-rays that can wipe out an atmosphere."

Characterising terrestrial planets is easier around smaller, cooler stars, said co-author Elsa Ducrot from the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) in France, who was on the team that conducted earlier studies of the TRAPPIST-1 system.

"If we want to understand habitability around M stars, the TRAPPIST-1 system is a great laboratory," she added. "These are the best targets we have for looking at the atmospheres of rocky planets."

Related News

- Astronomers from the University of Liege discover new planetary system

- Space telescope measures temperature of Earthlike planet 40 light years away

- Research on exoplanets proves more difficult than expected

Additionally, no evidence was found to indicate that the exoplanet has an atmosphere, which would lower the temperature by better distributing the heat around the surface.

"This planet is tidally locked, with one side facing the star at all times and the other in permanent darkness," said Pierre-Olivier Lagage from CEA, a co-author on the paper. This means that TRAPPIST-1b does not spin on its axis, as Earth does. "If it has an atmosphere to circulate and redistribute the heat, the dayside will be cooler than if there is no atmosphere."

Whilst this makes it unlikely that there is alien life on the exoplanets, the NASA experts stressed that the discovery highlights the capabilities of the James Webb telescope, which opens the door to even more striking and promising discoveries about other exoplanets, their atmospheres and temperatures.