This is not about politics or ideology. It's about a mother, Saliha Ben Ali, a victim of radical Islam, and the son she never had the opportunity to bury.

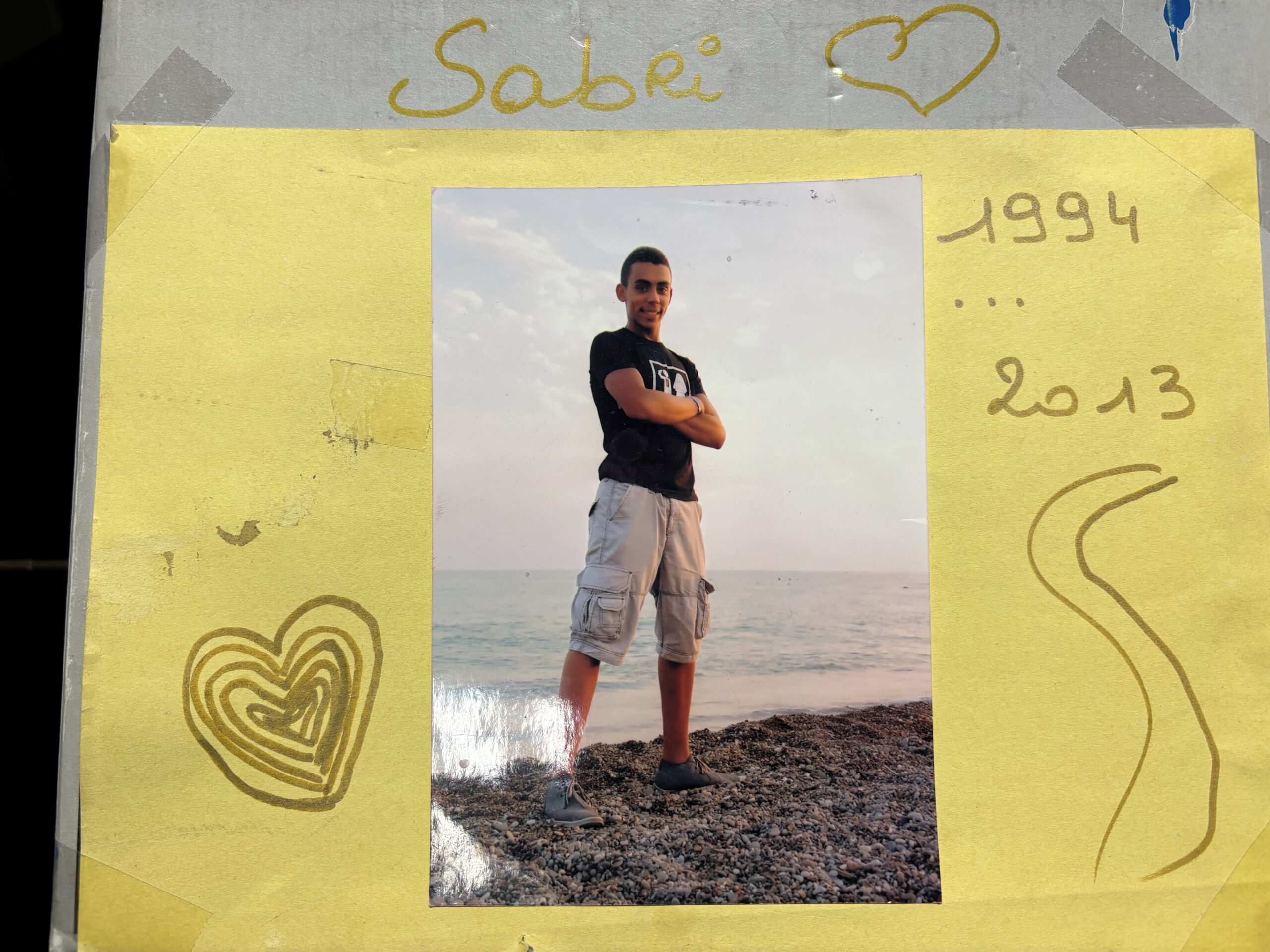

Sabri was 19 when he left Brussels. He never came back. He was executed somewhere in the Syrian desert. A decade on, his mother still hasn't seen a grave. But she has chosen to speak. Not to point fingers, but to ensure others understand how easily it can happen.

The boy who never came back

Nothing in the Ben Ali household screamed "radicalisation" ten years ago. Saliha was an ordinary mother from a working-class background in Belgium. Her son Sabri was a typical teenager. His dream was to become a professional basketball player. He sometimes skipped class to train harder. One day, he skipped breakfast in the morning and never returned.

She received a phone call from Syria in December 2013. It was the last time anyone heard from Sabri.

"He’s dead, but we can’t prove it," Saliha explains. Officially, Sabri is still considered a wanted person. Convicted in absentia for belonging to a terrorist group, to this day, he's a subject of an international arrest warrant. "Every year we get fined because he hasn’t filed his tax return," she says. “It’s hard because we can’t grieve properly"

She holds a small yellow box, made by Sabri’s little sister. Inside are photographs and keepsakes. "It’s his coffin, in a way," she says. "There is no grave. Nothing to bring closure."

The recrutement phase

Security services are aware that Brussels is seen as a recruiting hub for radical islamists. The State Security (VSSE), military intelligence (SGRS), and the Coordination Unit for Threat Analysis (CUTA) all monitor known radicalised individuals. Some roam free in the capital.

When asked whether any recent attacks had been foiled, Belgium’s Interior Minister Bernard Quintin (MR) responded cautiously: "Listen, I don’t know. But I can tell you that we are extremely vigilant," he said, referring to the coordination with international partners. "All these services function well. The coordination works."

But the law remains the law. And prosecution requires evidence – even when the warning signs are flashing.

Pieces of evidence, a flag of the Islamic State (IS) pictured at the trial of the attacks of March 22, 2016, at the Brussels-Capital Assizes Court, Tuesday, 06 December 2022. Credit : Belga / Didier Lebrun

"Radicalisation doesn’t always start with ideology. Often, it begins with a lost identity" Saliha stressed. "Discrimination, alienation, and an absence of belonging make some young Muslims in Europe acutely vulnerable to recruitment." She adds.

Sabri knew little about Islam. Religion was never part of the household. Saliha had grown up under a strict, pious father and had consciously chosen a different path for her children. They celebrated Eid more as a cultural tradition than a spiritual obligation.

When Sabri began attending the mosque in Vilvoorde, she assumed he was exploring his 'roots'. But things changed quickly. He stopped playing football. He removed his posters. He stopped listening to music. His father thought it would pass. Saliha feared otherwise. She couldn't do anything.

Soon, he was travelling further afield, to Schaerbeek, where he met members of the extremist group Sharia4Belgium.

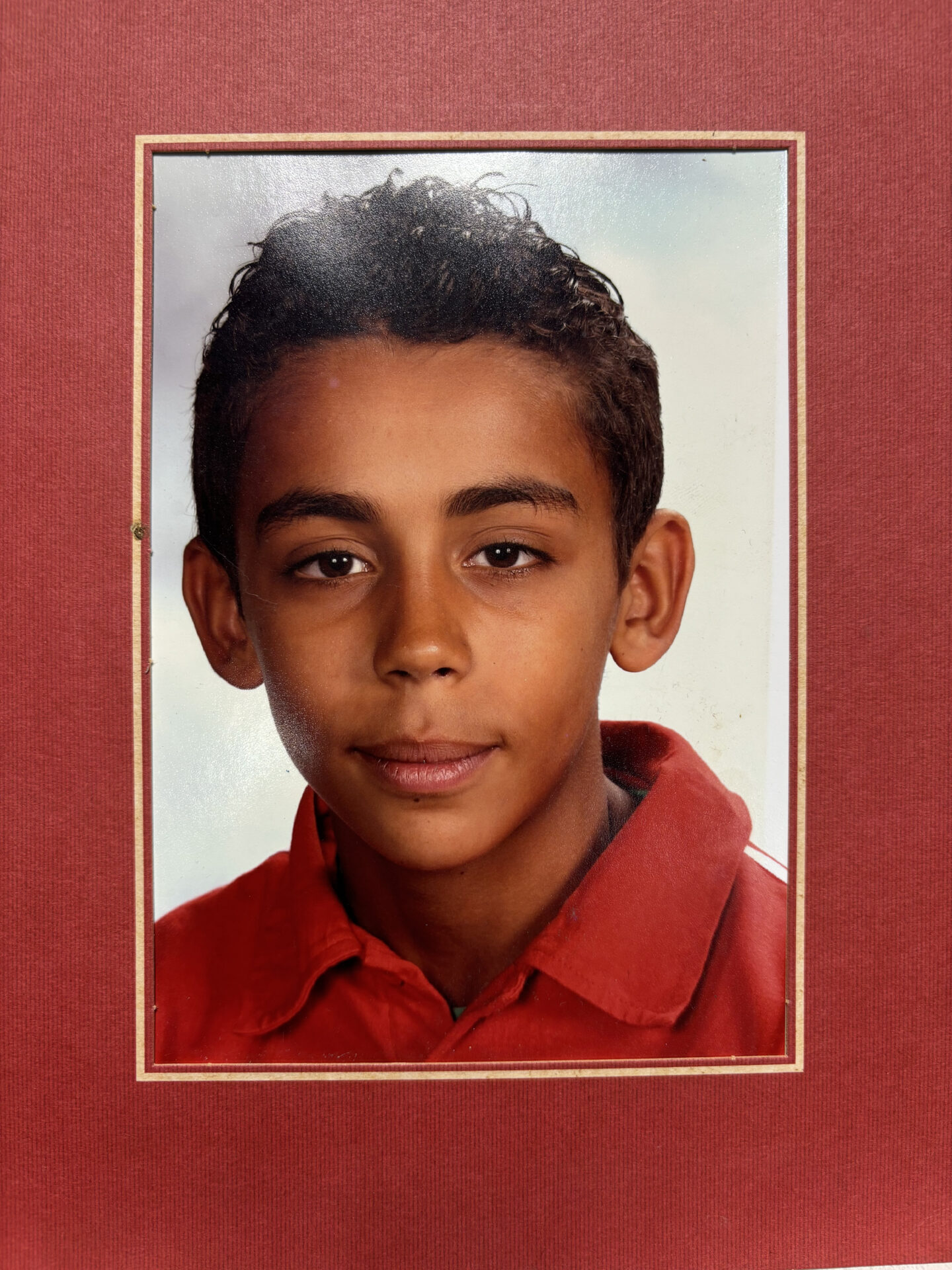

Sabri, Saliha's son at 9 years old. Credit: Anas El Baye.

Three Months to Syria

Summer 2013 was pivotal. Ramadan coincided with a trip to Morocco. "Sabri kept looking at me," Saliha remembers. "As if he’d already made up his mind."

Three days after returning to Belgium, Sabri disappeared. Police quickly confirmed he had flown to Antalya, Turkey. From there, he crossed into Syria.

A message followed via Facebook Messenger: "Mum, don’t be angry. I’ve gone to the Shām."

Sabri had joined Jabhat al-Nusra – then al-Qaeda’s branch in Syria – and was later accused of war crimes by several NGOs. The group had a shifting relationship with ISIS, with whom it occasionally collaborated.

Saliha doesn’t know whether her son fought or killed. There are no photos of him with a gun.

Yellow box containing Sabri's pictures. Credit : Saliha Ben Ali

A reckoning

Three years after Sabri’s presumed death, Saliha travelled to the Syrian border. She distributed bags of his clothes in refugee camps – a symbolic gesture, she says, to honour what she believes were his true intentions.

"I’m convinced he didn’t harm anyone. He sincerely wanted to help the Syrian people," she insists.

But the more profound truth is more complicated.

"I experienced Sabri’s disappearance like a kidnapping," she says. "As though someone had taken him from me."

Saliha has since become a vocal advocate against radicalisation. But her story is not one of vengeance – it’s one of grief, confusion, and the painful silence of unanswered questions.

Radicalisation doesn’t happen overnight. But in Sabri’s case, it took just three months.

And for his mother, it has meant a lifetime without closure.

How did Sabri end up on the frontlines of the Syrian war? Why did he become radicalised in just three months? Who is responsible?

Walking on eggshells

To answer this questions, is to walk on eggshells, because it's a very thin and fine line between faith and extremism when it comes to Islam. Like Christianity or Judaism, it encompasses a broad spectrum of theological interpretations, cultural expressions and political viewpoints. The moment Islam becomes 'radical' is not defined by piety or devotion, but by a shift in intent.

We can often trace this type of radicalism to the 18th-century puritanical movement of Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia, later weaponised by jihadist groups that reject democratic governance, pluralism and coexistence with non-Muslims. And the consequences are dire for the Muslim communities worldwide.

In countries like France, debates about Islam, secularism and identity have become daily flashpoints. Whereas in Belgium, it's mostly avoided. For political reasons; some say wrongly so.

In Muslim-majority countries, the threat is even more pronounced. From Nigeria's Boko Haram to Pakistan's Taliban, radical Islamist groups have targeted fellow Muslims in brutal campaigns, aiming to impose a strict, exclusionary version of Sharia law. But this is nothing new.

Countering radical Islam requires more than intelligence operations. It demands honest conversations about integration, education and religious literacy. But mostly: historical literacy. It also means supporting Muslim Europeans who believe religion can be separated from the state, including scholars and community leaders. In the meantime, other questions remain unanswered, and pointing the finger is to undermine the legitimacy of the collateral damages of radical Islam.