Over the last several days, concern has arisen over the use of the AstraZeneca vaccine against Covid-19, and the appearance of a number of cases of blood clots among people who have been vaccinated.

As a result, about a dozen European countries have decided to suspend use of the AZ vaccine until the situation can be clarified. The World Health Organisation has pointed out that the number of cases of blood clots is no higher among vaccinees than it might be expected to be among the population at large.

The European Medicines Agency concurs, and the Belgian health ministry has no plans to stop administering the AZ vaccine.

But the question we wanted to look at was: what are these blood clots, and how do I know if I have that problem?

First point: your blood is made to clot. If you have a minor cut, you will notice that the blood flows freely for a time, and then stops. That is the effect of clotting.

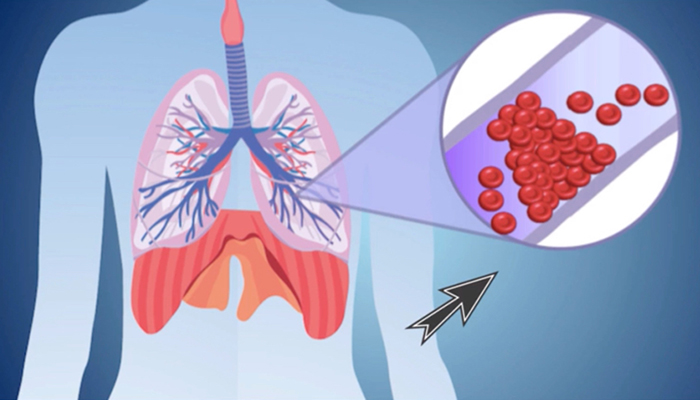

Your blood effectively contains three types of cell in a liquid called plasma: red blood cells, which transport oxygen to your organs; white blood cells, which combat infection; and platelets, which group together to form a barrier whenever you start to bleed into the out-of-body environment.

Those platelets are in your bloodstream at all times, but sometimes they gather together where there is no external wound, and that causes a problem.

Such is the power of platelets to stop blood flow – a power so essential when there is a wound – that when platelets gather in what is normally called a blood clot, but in the wrong place is called a thrombus or an embolism, it can be a medical emergency.

Related News

- Belgium's decision to continue AstraZeneca vaccinations, explained

- Blood-clots also happen without vaccines, says Belgian Health Agency

- EMA meets to reconsider AstraZeneca's vaccine

- AstraZeneca defends vaccine’s safety

In the case of the AZ vaccine, a number of cases have emerged of patients who were vaccinated, and later developed an embolism. That has led to a number of governments deciding to suspend use of the AZ vaccine until more details can be gathered.

What is very clear for the time being is that the number of cases of embolism following vaccination is very small indeed. So small that you would expect that number among the general population even if no vaccinations were taking place.

The governments concerned are claiming to be applying the precautionary principle, which translates in layman’s terms to ‘Better safe than sorry’. But they are first ignoring one of the primary principles of logic: Just because B follows A does not mean that A caused B.

In rhetoric, this is known as the fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc.

In science, it relates to the principle of correlation does not equal causation.

But if you were to be vaccinated, and you were to have an incident of embolism, how would you recognise it?

So far, the matter of blood clots following vaccination has been very vague. There are different kinds of embolism, going from the type in the lung, the pulmonary embolism (PE) which can be deadly (none of those seem to have arisen for the time being).

Otherwise, a blood clot may arise in the arm or leg, resulting in throbbing or cramping pain, swelling, redness and excess warmth. If these symptoms occur, seek medical help immediately. An embolism of this type should be treated as an emergency, since it can still travel to a major organ.

Alan Hope

The Brussels Times