On the southern edge of Brussels lies a realm of quiet enchantment. Nestled between the clatter of commuter trains and the rustle of broad-leaved canopies, Tournay-Solvay Park is an elegant anomaly – a historic estate turned urban refuge, caught halfway between decay and rebirth, culture and wilderness.

Marked by grandeur, decline, and reinvention, Tournay-Solvay Park sits on the southern fringe of Brussels. Part of the city’s Green Belt, or Promenade Vert, it is orbited by Boitsfort train station, the residence of the Japanese ambassador, and the International School. Its jewel is the recently renovated Château Tournay-Solvay. From scattered ruins of former inhabitants to ponds and orchards, it provides a less polished alternative to the city’s more manicured green spaces. And its juxtapositions are a fitting microcosm for the patchwork city of Brussels.

Despite its generous acreage and noble pedigree, it remains one of the city's least-known green spaces. Overshadowed by more central and better-groomed parks, it offers something altogether more compelling: a layered landscape of memory and moss, of rare trees and secret caves, of ruins and rebirth. In a city that often feels like a mosaic of contradictions, this park may be its most eloquent microcosm.

The story begins in 1877 when industrialist Alfred Solvay – of the Belgian chemical dynasty – purchased a swathe of forested land and set about creating a retreat in the style of an English country estate. The centrepiece, Château Tournay-Solvay, rose the following year in Flemish neo-Renaissance splendour: gabled, turreted, and resolutely dignified.

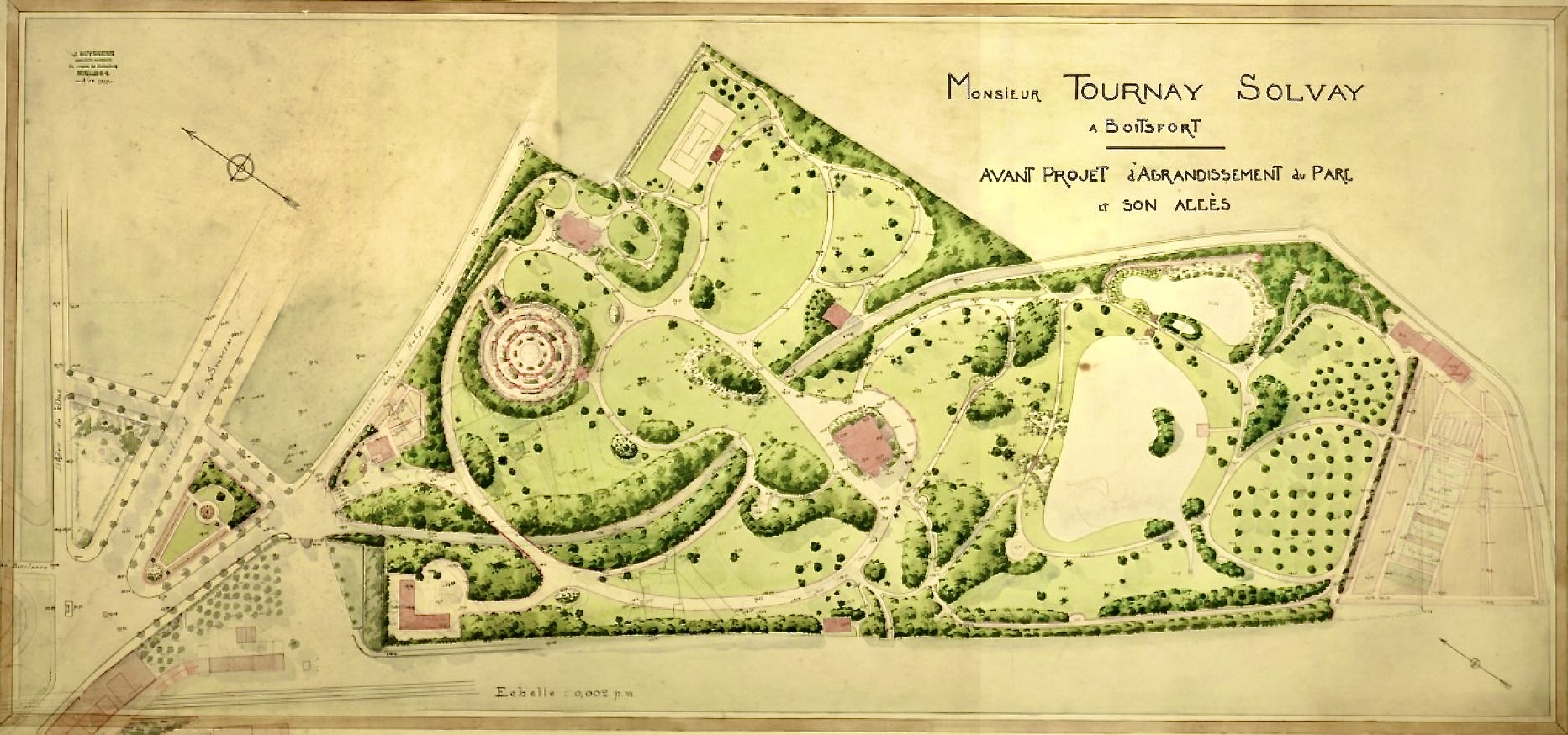

The Jules Buyssens plan for the Tournay-Solvay Park

Solvay’s daughter, Thérèse, inherited the property and expanded its cultivated grounds after her marriage to Émile Tournay. The union bestowed the double-barrelled name the park bears today. In 1911, renowned landscape architect Jules Buyssens was enlisted to lay out the gardens, and he returned in 1924 to design the rose garden – a gem of botanical formality within a park that would come to celebrate the unkempt.

But beauty fades. After Thérèse’s death in 1972, the estate slipped into decline. The chateau was abandoned, its windows broken, its rooms looted. In 1982, it was ravaged by fire – suspected arson – leaving behind a blackened husk that loomed like a ghost over its withering grounds. By 1985, the ruins formed a spooky centrepiece for a newly opened public park. In the same year, the rose garden and orchard were restored. The park’s path to preservation was neither quick nor straightforward but its status as a protected heritage site was formalised in 1993.

But its renaissance has been anything but sterile. Rather than sanitising its history, Tournay-Solvay has embraced it. It is now a place where trees grow crookedly, ruins are left to rot gracefully, and wildness is not a flaw but a feature.

Blend of styles

Covering seven hectares, Tournay-Solvay Park is a patchwork of meticulously planned gardens sitting alongside wilder, more organic spaces. The vegetable garden, perched at the park’s highest point, retains something of Buyssens’ original design that challenges the rest of the park's more naturalistic vibe.

But this polished beginning soon gives way to wilder territory. A descent leads visitors to the large central pond, fringed by wetlands that form part of the EU’s Natura 2000 biodiversity network described as the “backbone of European nature policy”. This ecological status protects a rich diversity of species: amphibians, waterfowl, aquatic plants, and the insects and birds that depend on them.

Pond inside Tournay-Solvay Park

Remarkable trees include a Bysance hazel also known as Turkish hazel – unique for growing as a tree rather than a shrub – as well as a purple beech, broad-leaved lime trees, a Japanese dogwood, and even a Lebanese cedar. The vegetable garden has medicinal, condiment or perennial plants and fruit trees. These stately inhabitants contribute to the sense of being in another time and place.

Near the pond, various marsh plants include telekia from southeastern Europe, among some 120 herbaceous species. Huge rhubarb-like leaves around the banks of the pond are butterbur. And around, these you might spot red-legged frogs, tufted ducks, herons, amid other local personalities. The ponds teem with fish including perch, pike, and bream.

It’s a park for all seasons. In spring, the orchard explodes in blossoms; in summer, frogs leap among lilies and dragonflies patrol the air. Autumn sets the trees ablaze with reds and golds, while in winter the park retreats into a skeletal quiet, interrupted only by the flash of a bird or the crunch of frost underfoot.

The park also features a mix of pathways — some manicured and gravelled, others narrow and overgrown. The orchard has a charming forgotten feeling, with apple and cherry trees nodding to an agricultural past. The old greenhouse, too, stands as a relic, its iron framework suggesting utility overtaken by nature.

One of the park’s strangest features is the separate sunken path that runs straight through – or beneath – it. This isn’t the disruption it might seem. Far from spoiling the atmosphere, the path lends the park a strange pulse: the elegant iron footbridges and stone tunnels that top it are overgrown with ivy and moss.

Ville Blanche inside Tournay-Solvay Park

Other buildings than the château are exquisite examples of period architecture. To the right of the main entrance stands the castle’s former stables, built in 1920, restored in 1992, and now housing the Centre Regional de l’Initation à l’Ecologie, a local assocation that promotes responsible attitude towards the environment, notably through activities with schools. There is also the Villa Blanche, designed in the early 20th century to house visiting friends of the Tournay-Solvays, and now occupied by the European Foundation for Sculpture.

In the old gardener’s house, lives Sitki Akcelik with his family, an employee of Brussels Environment as concierge and guardian of the park. Since the park opens and closes at night, he sometimes needs to let trapped wanderers out.

He lives in the grand old house with bats in the attic, which he can’t access, since they are part of the park’s protected wildlife. But the sounds are just part of the nocturnal audio landscape he inhabits. Akcelik laments the loss of trees to climate change – too much rain followed by strong winds turns soil to clay and trees become “like glass” – liable to topple over.

The gardeners don’t curate the park for its visual aspects, preserving its wild status as a protected terrain. But they do plant trees with maximum respect for the topography of the site. Meanwhile, dead trees are mostly left as a haven for biodiversity – providing nesting material for the park’s smaller inhabitants.

Garden inside Tournay-Solvay Park

Walk the talk

Tournay-Solvay Park can be enjoyed through a walking loop. Enter via the main entrance near the station and the Chaussée de La Hulpe, and head up a tree-lined path, catching glimpses of the park’s mix of cultivated and wild spaces. Perch at the first wooden bench to take in a panoramic view of the park’s rolling landscape.

From there you arrive quickly at the Château Tournay-Solvay, the park’s historic heart. Interpretative panels are dotted around to explain a little context. Look up top and you’ll see how the modern physics research centre has been built into the roof of the castle. And don’t miss the ornamental details on the château’s surviving brickwork.

As you follow downhill, you’ll hit the large central pond. At the wooden observation deck, muse on the wetlands and assortment of aquatic wildlife. The spot is particularly striking with the coloured leaves of autumn but has something to offer the spirit in each season.

Trace the narrow path upward towards the old orchard, and you might come across blossoming fruit trees in spring or ripe hanging fruits in late summer or early autumn. The remnants of the greenhouse in wrought iron and brickwork, somewhat poetically overgrown, are here as a reminder of the estate’s agricultural past.

Continue along the wooded path to the right to enter a more secluded forest area, with a wild, untouched feel and a sense of how Brussels might have been when carpeted with woodland. Old bridges and stone walls blend into the forest with the sounds of birds and rustling leaves, giving the sense of a secret refuge.

'Olmec head 8' inside Tournay-Solvay Park

The path opens into a wide-open meadow. Drink it all in – ideally at golden hour – before heading back. The tree-lined promenade will take you back to the entrance on Chaussée de la Hulpe where a final turn back will reveal the château framed by its surrounding vegetation.

Away from the main paths and concealed by bracken and brambles between the pond and the wall, lies a lesser-known feature of Tournay-Solvay: a bat shelter in a repurposed icehouse. Amongst the bats welcomed are the whiskered bat, the common serotine, Bechstein's bat, Brandt's bat, Nathusius’s pipistrelle and the common noctule. An information board nearby says the icehouse, which looks like a sentry box built into a rising bank, keeps the temperature at a constant low, even in summer.

Bats spend the winter in hibernation, it notes, with three factors determining whether a space is a good wintering place: high relative humidity, constant temperature and quiet. “If they are disturbed while hibernating, they must draw on their precious fat reserves, which can be fatal,” it says. “Thanks to their cave-like climate, ice houses are perfectly suited for hibernation.

Locals whisper childhood stories about the “bat cave,” and conservationists have taken care to keep the site undisturbed. In spring, ferns spill across its entrance, giving it the look of a portal into older times. Though shallow, the cave’s cool air and dripping ceiling evoke an otherworldliness – a miniature underworld tucked inside an urban park.

Memory in stone

Amid the trees and paths are several sculptures, each telling its own quiet story. The most prominent is a replica of the Olmec Head no. 8 – a mysterious monolith with African features, modelled by artist Ignacio Pérez Solorzano on a 3,000-year-old pre-Columbian original discovered at the Mexican archaeological site of San Lorenzo – a surprising emissary from a history far further back than the Solvay heritage.

There is also the sculpture of a young girl who died at age 22, Kelda Spangenberg, commissioned by her bereaved parents, and resembling both a woodland fairy and benevolent ghost. An example of the quiet magic found in the corners of this strange, beautiful park.

Related News

- Belgium launches campaign to revive love for pears

- Why Belgium’s energy future is blowing in the wind

- Shrimp riders of the North Sea

- Belgium’s rich and often overlooked musical Golden Age

- 'The castle had burned twice, and all that remained were ruins'

- Hidden Belgium: Hot chocolate at one of the most intriguing castles in the country

- Toxic blue-green algae found in Brussels ponds

- Former PM De Croo lands a top job at UN