Amsterdam is just 90 minutes from Brussels by train, but this week it feels even closer. Open now at the Rijksmuseum, Metamorphoses is one of the most ambitious exhibitions mounted anywhere in Europe this year – and it does so with a distinctly Belgian accent.

René Magritte, Paul Delvaux, Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob Jordaens all feature prominently in a sweeping show that traces 2,000 years of artistic obsession with transformation, desire and power, inspired by Ovid’s epic poem of the same name.

The exhibition, developed in close collaboration with Rome’s Galleria Borghese, brings together more than 80 works ranging from antiquity to contemporary video art. But for Belgian visitors, it is striking how naturally the country’s artists anchor the story – especially through surrealism.

A large 1937 canvas by René Magritte, Le Modèle Rouge III (The Red Model III), in which bare human feet morph disturbingly into leather boots, serves as a quiet, unsettling punctuation mark to the show.

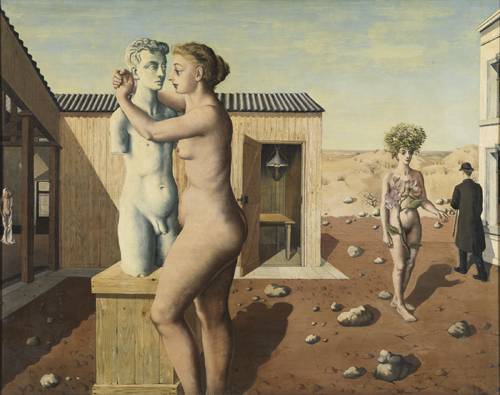

Nearby hangs Paul Delvaux’s 1939 Pygmalion, a dreamlike inversion of the classical myth in which a nude woman clings to a male statue – desire, agency and illusion gently scrambled.

Paul Delvaux, Pygmalion 1939

For Rijksmuseum director Taco Dibbits, the inclusion of Belgian surrealists was deliberate rather than decorative. “For the surrealists, everything is fluid,” he explains. “There’s always a sense of humour, of turning things around. And that idea – that the soul can take many forms and morph itself – is absolutely central to Metamorphoses.”

Surrealism, he argues, may not be the first movement associated with Ovid, but it embodies the ancient poet’s obsession with unstable bodies and shifting identities.

If the modern Belgians bring psychological unease, the old masters deliver muscular drama. Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob Jordaens (The Abduction of Europa) appear as part of a powerhouse group that includes Titian, Correggio and Caravaggio, artists for whom Ovid was once described as a Bible.

Rubens’ voluptuous mythologies, thick with flesh and movement, underline how central transformation – bodies in flux, passions boiling over – was to Baroque art in the Low Countries.

From there, the exhibition – which has an audio guide by Stephen Fry – expands outward and backward. Bernini’s Sleeping Hermaphroditus, on loan from the Louvre, remains one of the show’s great showstoppers: a figure whose apparent femininity dissolves into anatomical ambiguity as the viewer circles the marble bed.

Caravaggio’s Narcissus captures a youth frozen at the moment of fatal self-recognition, his reflection as seductive and treacherous as any god in disguise. Rodin’s Pygmalion and Galatea shows stone itself seeming to soften under human touch.

The curators do not shy away from the darker undercurrents of Ovid’s tales. Jupiter’s repeated transformations – into bull, swan, cloud or shower of gold – are presented alongside wall texts that acknowledge how coercion and violence thread through the myths.

Dibbits is careful to frame these episodes not as moral endorsements but as attempts to humanise overwhelming forces of nature. “When people are touched by this enormous godly power,” he says, “a total transformation takes place. It’s about fears and passions, joys and sorrows – things that are intensely human.”

Contemporary artists push that reckoning further. Louise Bourgeois’s giant spider, born of the Arachne myth, looms as both protector and threat. Video works by Juul Kraijer recast Medusa not as monster but as unsettling, silent presence, her snakes gliding calmly across a human face.

Metamorphoses argues that change itself is the only constant – in myth, in art, and perhaps in Europe.