Last weekend’s Black Lives Matter demonstrations were initially inspired by the death of a black man at the hands of police in Minneapolis in the US. But they soon turned attention on matters closer to home.

Not only does Belgium have its own problem of police and racial profiling, but the George Floyd demonstrations opened up once again the country’s own history of colonialism and racial conflict.

That resulted in the vandalism and destruction of the many statues to Leopold II, the country’s second monarch, and Belgium’s history of colonialism in the Congo.

Léopold Louis Philippe Marie Victor was born only four years into his father’s reign as the very first King of the Belgians. He was his father’s second son, but the eldest to survive.

He took the throne on the death of Leopold I’s death in 1865, and reigned until 1909, when the throne passed to his nephew Albert I. The royal line since then descends from Albert, and not from Leopold.

On his birth, his older brother having died, he was given the title of Duke of Brabant, which is a popular name for pubs in Belgium, though many may not realise the name refers to Leopold II.

Leopold’s reign was marked by a number of progressive developments, including the creation of a network of primary schools independent of the Catholic church, laws against child labour and the right to create free trade unions.

Nonetheless, Leopold II’s heritage will be hereafter linked to his desire, expressed in a letter to his younger brother Philippe in 1888, in which he states that “the country must be strong, prosperous, therefore have colonies of her own, beautiful and calm.”

The reality would turn out to be something quite different.

Leopold II would earn himself the name of King-Builder, based on the number of monumental construction projects he made happen, from the Africa Museum in Tervuren to the avenue leading to the Cinquantenaire Arch and park in Brussels, as well as the Royal Galleries in central Brussels, and the monumental central station in Antwerp.

But those monuments, fit for any Pharaoh, were built on the blood of the natives of the Congo.

Leopold had engaged the Africa explorer Henry Morton Stanley, to prepare his claim to the land now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo. However unlike most European monarchs, Leopold did not claim the land in the name of his country, but in his own personal name.

The Berlin Conference of 1884-85 approved this unusual approach, but insisted on a number of conditions.

Leopold, through his Force Publique, would go on to to ignore those conditions, and oversee the governance of the Congo as his personal fiefdom and his own source of personal riches.

Arguments against colonialism begin and end with Leopold II. White western nations have exploited other parts of the world to an undeniably horrific extent, of that there can be no doubt.

In only one instance was that sort of exploitation carried out for the personal enrichment of one man. And that man was Leopold II, King of the Belgians.

The atrocities have been well documented.

While Leopold harvested massive riches from the exploitation of the natural resources of Congo, his colonists brutally exploited the people of the area to an extent unseen elsewhere. Amputations were considered a daily occurrence, where other colonialist oppressors took whipping to be the punishment du jour.

African people – men, women and children alike – had their limbs chopped off by colonial overseers, for the slightest of offences.

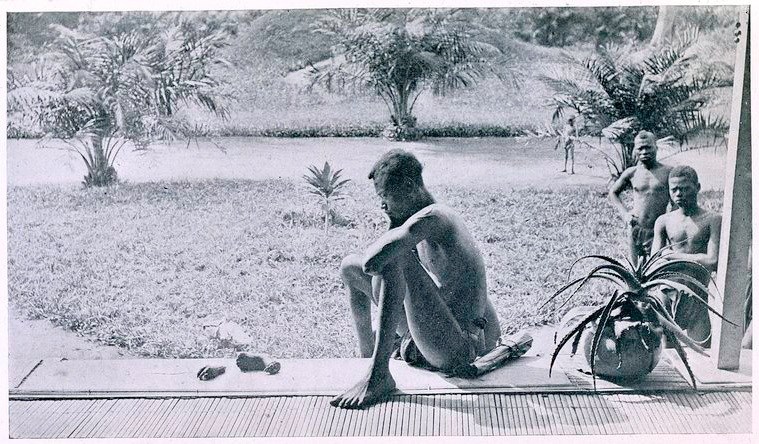

In the case of the photo accompanying this article, a father contemplates the hand and foot of his five-year-old daughter, who had been punished for failing to meet her quota of rubber collection under Leopold’s administration.

As far as the death toll attributable to the rule of Leopold II in Congo, any number is likely to be close. Deaths attributable to the colonial regime – which had after all ignored the conditions laid down by the Berlin Conference of colonialist nations – range from one to fifteen million. The most reliable, though nothing in this matter can be said to be truly reliable, put the figure at about ten million, or half the population of Congo at the height of the Leopold era.

The Belgian involvement in Congo did not, of course, end with the death of Leopold II. The government, now faced with a demand to open that particular Pandora’s Box, should now be prepared to face whatever else may be revealed, not least the Belgian government’s role in the assassination of Congo’s first elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, as well as the activities of some huge Belgian corporations in the colony.

Alan Hope

The Brussels Times