Marcel Broodthaers’s work extended far beyond the surrealist paintings and mussel-themed art installations that earned him an international reputation in the 1960s.

The influential poet, painter, photographer and filmmaker, who died in 1976 aged just 52, was disillusioned with Brusselization (or Bruxellisation), the ruthless modernisation of his native city, and advocated for more humanistic design.

He had witnessed first-hand the drastic urban transformations that reshaped Brussels. During his youth, the city underwent major reconstruction, including the North-South railway connection, the remodelling of the ring road, and the demolition of iconic Art Nouveau masterpieces like Victor Horta’s Maison du Peuple.

Most controversially, the so-called Manhattan Project in the city’s northern quarter displaced some 15,000 residents to make way for high-rise business developments. His responses to these sweeping changes positioned him as an uncompromising critic of modernist architecture and its detachment from human experience.

A recent exhibition at architecture museum CIVA, Marcel Broodthaers – The Architect is Absent, which closed in June, showed how these transformations influenced his artistic career.

The exhibition’s title referenced a phrase Broodthaers coined in 1967, questioning architecture’s functionalist principles and social role. It suggests that without control, a more humane and poetic living environment might emerge. This idea ties into his larger body of work, in which he repeatedly challenged the rigid definitions of artistic media, questioning the relationship between image and meaning, form and function, reality and representation.

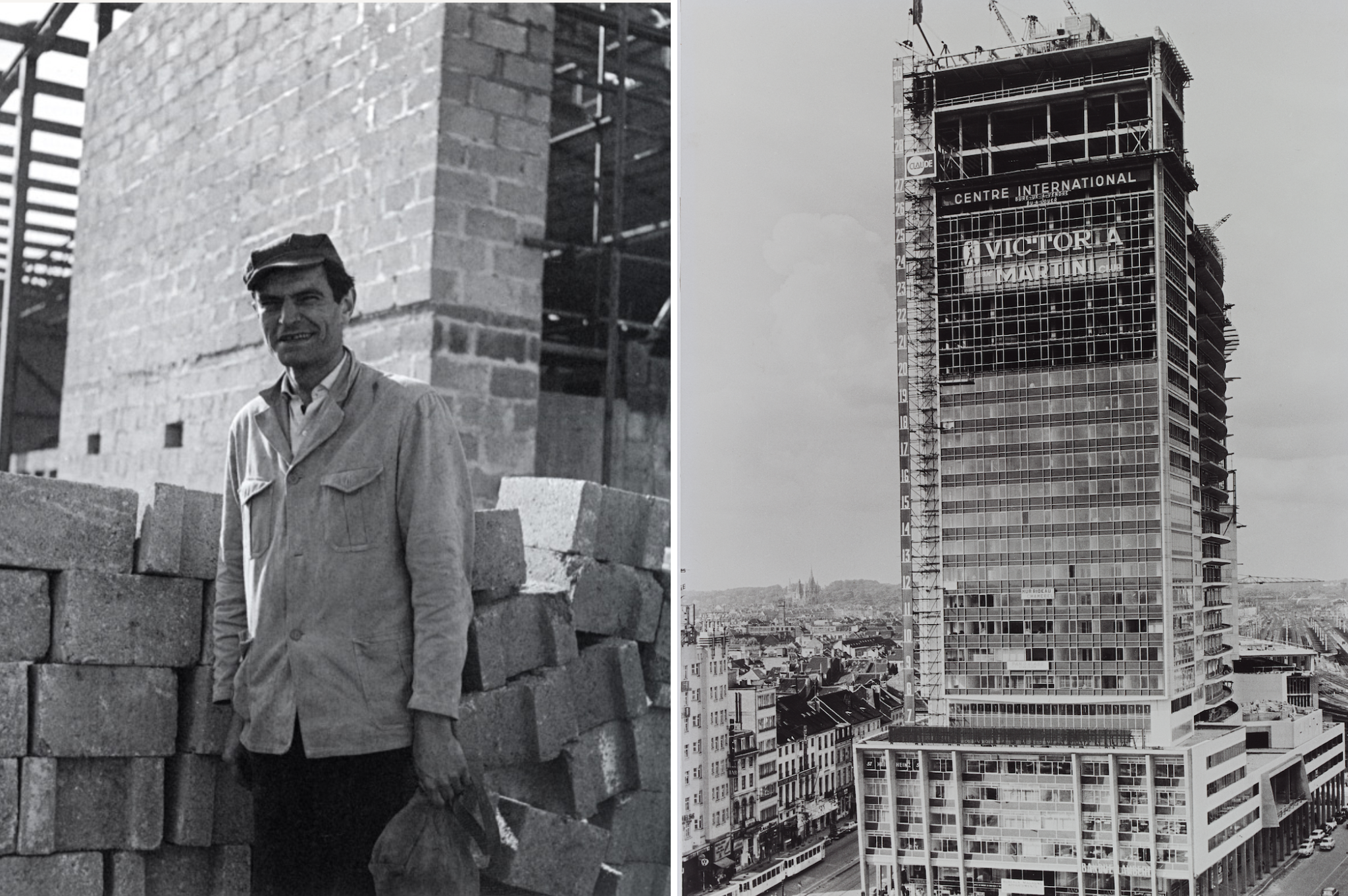

The key exhibit was Monument Public, a reference to the Martini Tower, built in 1957 and demolished in 2002. Other highlights include his magazine cover photo of the Maison du Peuple, protesting its demolition, poignant images of the Marolles district, and articles criticising dehumanising modernism. Broodthaers even rejected the optimism of Expo 1958, saying that its centrepiece, the Atomium, “speaks more to our imagination than to our sense of reason.”

Belgian poet and artist Marcel Broodthaers (1924-1976) as he performs in the movie "Interdiction de Fumer" of 1967, photographed as part of a previous exhibition in the Fine Arts Museum, in Brussels. Credit: Belga

Modern and commercial

Broodthaers led a tumultuous life. Struggling as a poet, he wrote at 40: “For some time, I had been no good at anything.” This sense of failure and disillusionment – shaped by writer Charles Baudelaire’s melancholic reflections on urban renewal in mid-19th century Paris – fuelled his transition into the visual arts, where he could explore the tensions between art and language, materiality and ephemerality

His artistic practice was often playful yet deeply subversive. One of his best-known works, Pense-Bête (1964), consisted of a stack of his unsold poetry books encased in plaster, rendering them unreadable. This act of self-erasure, both an elegy and an ironic statement on the commercial value of art, marked the beginning of his conceptual explorations. He went on to create fictional institutions, such as the Musée d’Art Moderne, Département des Aigles, a critique of museum culture that blurred the boundaries between real and imagined spaces.

Two people admiring a work of Belgian poet and artist Marcel Broodthaers (1924-1976) at the inauguration of his exhibition in June 2001 in the Fine Arts Museum, pictured on Friday 9 March 2001, in Brussels. Credit: Belga

The Centre International Rogier (Jacques Cuisinier, Serge Lebrun, 1957-1958), Brussels’ first true skyscraper, embodied the shift Broodthaers so often criticised. Known as the Martini Tower due to its rooftop bar and neon Martini sign, it represented both modern life with its shops, hotel and car parks, and privatisation. Broodthaers saw it as an “iconic, oft-reproduced building” but also a symbol of growing commercialism. His scepticism toward modernity extended beyond architecture, encompassing the entire economic and political framework that underpinned it.

Beyond Brussels, he criticised the rigid sterility of Le Corbusier’s housing blocks and wrote in 1963 that these complexes bred “deadly boredom” and social unrest. His concerns remain relevant today, as urban landscapes continue to grapple with issues of gentrification, alienation and the erasure of historical memory.

CBR building in Brussels

While he mistrusted technology, he collaborated with architect Constantin Brodzki on the futuristic CBR building in Watermael-Boitsfort, a striking tower featuring oval, tinted orange glass set into concrete. In a 1970 interview, Broodthaers poetically likened the building, now co-working space and café Fosbury & Sons, to “a fishbowl.”

For CIVA exhibition curator Stefaan Vervoort, Broodthaers’s humanism manifested itself in several ways: his emphasis on handcrafted artistic expression over mechanised industry, his use of familiar everyday materials and his focus on preserving history and memory. Broodthaers viewed traditional objects as carriers of cultural memory, in contrast to the disposable, 'amnesiac' nature of modern materials like plastic.

Although Broodthaers did not directly influence architects, his artistic approach allowed him more freedom to challenge architectural norms, Vervoort says. His photographs of Brussels – capturing the Palace of Justice, Marolles district and the doomed Maison du Peuple – reflect his desire to preserve history against unchecked modernisation.

Photograph of Brussels, c.1957 by Marcel Broodthaers

His Expo 58 images, including those of the Congo Pavilion, are paired with articles criticising the exploitation of workers and the empty promises of scientific progress. One of the exhibition’s most striking pieces was a 1957 photograph by photographer Julien Coulommier showing Broodthaers – for once, smiling – at a construction site in Heysel. This fleeting moment of apparent optimism contrasts sharply with the broader themes of his work, underscoring his complex relationship with progress and modernity.

Given his apparent enjoyment of building, could Broodthaers have become an architect if he had lived longer? “No, absolutely not,” says Vervoort.

Broodthaers never seemed interested in offering solutions; rather, he sought to expose contradictions, challenge conventions and provoke thought. “He would have continued critically mimicking the profession, creating architectural plans, models and projects within the sphere of visual arts, including plans, maquettes or projects,” Vervoort says.