If stripping the flesh from a kangaroo carcass is the price of admission to Brussels’ labyrinthine Museum of Natural Sciences, then so be it. Science is not always for the squeamish.

That kangaroo, it turns out, once bounded around Antwerp Zoo, and its bones are now destined to live on, meticulously cleaned and catalogued, as part of one of Europe’s great collections of natural life. The stench is terrible – pungent enough that the taxidermy department has been banished to a separate building. But for Olivier Pauwels, the museum’s curator of recent vertebrates, this is all part of the daily rhythm of research. “Think you can cope with the smell?” he teases.

Pauwels is a man enjoys unsettling his visitors. Ask him about dogs, and he’ll claim to despise them. Then he’ll casually mention he’s eaten one, along with porcupine and other exotic meats encountered in the field. He delights in these small provocations, perhaps because he spends much of his working life with creatures that cannot answer back.

His office is high in one of the museum’s towers, overlooking Brussels, though he spends more time looking down the eyepiece of a microscope than out across the city.

Olivier Pauwels, the museum’s curator of recent vertebrates

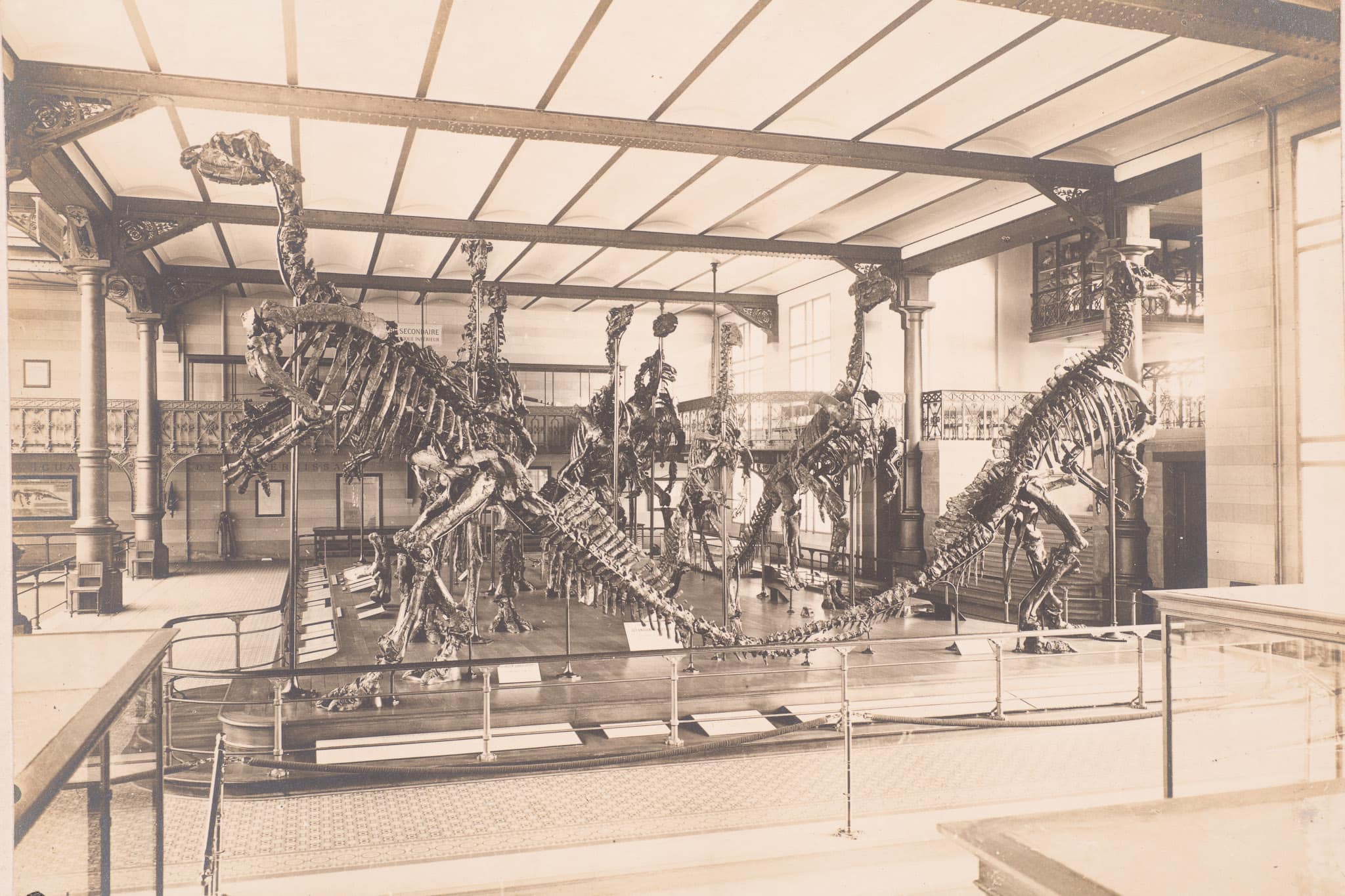

The museum is part of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (KBIN-IRSNB). It’s a scientific nerve centre. To the public, it’s perhaps best known for its dinosaur gallery – Europe’s largest – where 30 iguanodons discovered in a 19th century Belgian coal mine charge forever in the same direction, frozen mid-stride. But beyond the glass cases and reconstructed Neanderthals lies something more important: a working institution quietly cataloguing life on Earth.

“Why is it so important to classify all these animals?” I ask. It’s an obvious question, but one that Pauwels answers with patience.

“The real goal isn’t just to slap a name on something – it’s to accurately record and understand biodiversity,” he explains. Every organism pinned, bottled, or mounted in the Institute is a data point in an immense story: the planet’s living archive.

Here, time feels stretched. New species don’t evolve in a decade; they take hundreds of thousands, even millions, of years to appear. Yet extinction can happen overnight – and often does. “Many species go extinct before we ever even discover them,” Pauwels says. “Every species we describe is a small victory.”

The extinct thylacine, or Tasmanian wolf

There is, tucked away in the institute’s north-facing tower, a section of nameless beings – specimens preserved but not yet classified. They wait in their drawers, somewhere between discovery and oblivion, dependent on whether someone has the time and expertise to study them. The metaphor is irresistible: shelves of creatures hovering between existence and non-existence, their fate decided by the stroke of a pen.

When a species is on the brink, urgency sharpens the work. “If a limestone cave gecko is at risk from cement quarrying, we prioritise describing it,” says Pauwels. Only once a creature has a name can it truly enter the legal and conservationist machinery that might protect it.

Naming the world

Pauwels has classified hundreds of creatures. Identifying the genus (‘homo’ in homo sapiens, for example) is the easy part and doesn’t take long. “You can’t just write ‘fish’ in a register. Nobody would come see it. But if you specify a genus, it becomes relevant. That’s my speciality: genus-level morphological identification. I work with a microscope, then log them into the online register.”

But the fun starts when identifying species (‘sapiens’ in homo sapiens). It can take months, sometimes years. It may involve comparing specimens across the world – London, Stuttgart, Washington – and deciphering century-old descriptions that amount to little more than: it’s brown, 30cm long.

New image of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences' famous mammoth

Species naming comes with rules, rituals, and flashes of poetry. You can’t name a species after yourself, which has forced Pauwels into acts of generosity. He has named creatures after colleagues and conservationists: Gecko nutae, for instance, honours a pioneering Thai herpetologist, Professor Nuta Pandananda. Sometimes the names nod to mythology or metaphor. A black gecko speckled with white was christened Gecko pradapdao – Milky Way in Thai.

The labour is meticulous, yet it holds a peculiar thrill: the possibility of being the first human to recognise, truly, that this creature is new to science.

The thrill, too, comes with a certain melancholy. To name a species is to acknowledge it – but also to confront the fact that it might already be vanishing.

Eccentric history

The Institute’s grandeur hides a long, eccentric history. Its origins lie in the 19th century, in the private collection of Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine, who delighted in bones, minerals, and stuffed beasts. Housed first in the Palace of Nassau near the Mont des Arts, the growing collection soon spilled out. By the 1880s, it had moved into the Convent of the Redemptoristines in Ixelles, though the nuns never actually moved in. Perhaps they, too, were repelled by the taxidermy fumes.

Later, the modernist architect Lucien De Vestel – who would go on to design the European Commission’s Berlaymont headquarters – reshaped the institute between the wars. His two soaring towers, connected by a sweeping red marble staircase, are where today’s researchers scurry between labs and storage rooms. De Vestel even designed the drawers themselves: bespoke cabinetry for millions of specimens.

An old image of the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences

The institute’s royal patrons added glamour and, occasionally, eccentricity. Leopold III, Belgium’s controversial wartime king, was an enthusiastic amateur naturalist. “He made many field trips and discovered a lot of species,” Pauwels notes, with a touch of pride. For a monarch more often remembered for political scandal, it is a reminder that science and power have long intersected in unexpected ways.

During the Second World War, the Germans occupied the institute – it stood then as one of Brussels’ highest vantage points – but its collections survived intact. Today, the building is both fortress and ark, sheltering 38 million specimens. That makes it Europe’s third-largest collection, trailing only London’s Natural History Museum and Paris’s Institute of Ecology and Environmental Sciences.

Skeletons, dinosaurs, and Spy Man

Of course, the public comes for the dinosaurs. The Bernissart iguanodons, discovered in 1878 deep in a Walloon coal mine, remain the centrepiece. Unusually, the skeletons were found in lifelike positions, enabling scientists to mount them as if caught mid-charge. They stand today as a herd, their bones arranged with almost balletic drama.

But there are subtler treasures. The so-called Spy Man fossils – remains of Neanderthals excavated in the Spy cave near Namur in the 1880s – still anchor the museum’s exploration of human origins. For schoolchildren wandering the galleries, the leap from dinosaurs to Neanderthals to a hall of preserved aphids and zebras is dizzying. Yet it mirrors the strange continuity of natural history itself: everything, from insects to kangaroos, is part of the same ledger.

Squid jars at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. Credit: Danny Gys

Behind the glass, in those north-facing towers, the museum’s true wonder unfolds. There, millions of jars, skeletons, and skins rest in carefully controlled darkness. Each one is a story awaiting a reader. To walk the aisles is to step into the dream of an infinite library – only here the volumes are biological, the words written in bone and feather and fur.

Science after hours

The museum closes at dusk. The security guards usher out the last of the school groups and selfie-takers. Yet somewhere, in a side building, the kangaroo is still being stripped for bones. Pauwels jokes about being locked in, about my Night at the Museum fantasy of wandering among iguanodons and Neanderthals. But there is truth in the joke. To remain inside after dark would be to sense the weight of all that biodiversity – 38 million preserved lives – pressing in.

Stuffed birds at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences

When I leave, the stench of kangaroo clings faintly to my clothes. “Wait till you get home,” Pauwels had warned. “Anyone you meet this evening will smell it immediately.” But the odour seems fitting. Museums are not meant to be sterile, lifeless mausoleums. They are places where flesh becomes bone, bone becomes data, and data becomes knowledge – sometimes with a whiff of decay in the air.

And that is the paradox of Brussels’ great museum: it is both archive and laboratory, past and present, shrine and workshop. It preserves death so that life – in all its variety, fragility, and strangeness – can be better understood.

Latest edition of The Brussels Times Magazine is out now!