Since cities account for over 70% of global CO2 emissions but occupy around 3% of global land space, rethinking urban spaces is crucial to combatting climate change. Sustainable landscape architect Bas Smets knows this better than most people and is on a mission to transform cities and create micro-climates.

In conversation with The Brussels Times, Smets explained that he sees his role as an architect as more than just making things look nice: "It's beyond aesthetics; it's a need to keep cities liveable." The landscaper seeks to bring nature into the artificial environment of cities.

During last week's Tech for Climate conference, Smets stressed that his approach is modern and forward-facing, seeking to learn from nature and use it as a framework to improve city landscapes by creating micro-climates within them.

Self-sustaining solutions

Smets and his team work on self-sustaining developments that bring financial, as well as environmental, returns: "We think about how much rainfall a site gets and how we can keep that rainwater so that vegetation can use it later on. The idea is that every drop is collected and only leaves through roots or evaporation. This cools the immediate surroundings."

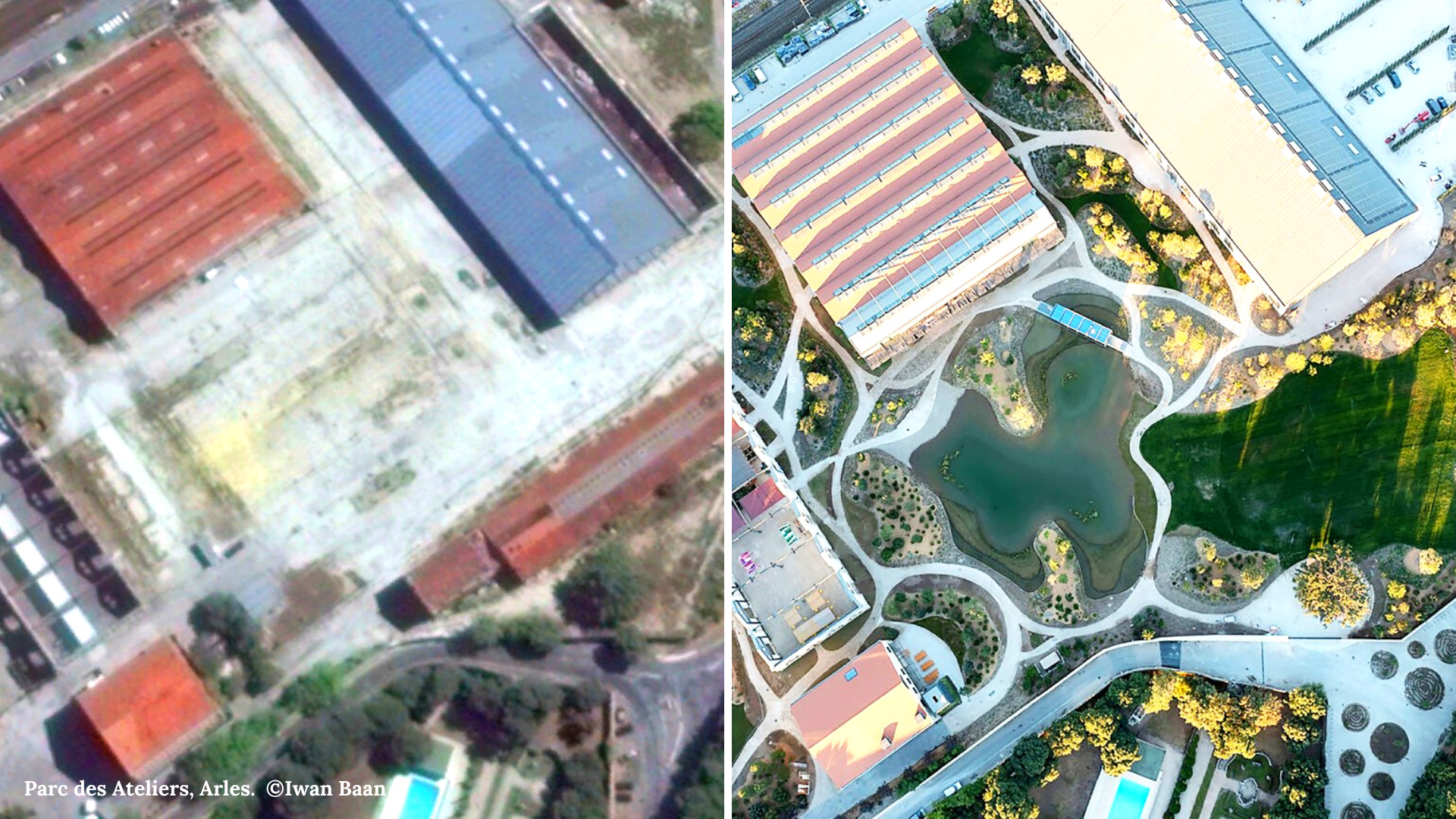

One example of such a micro-climate is in Arles, South of France, where Smets transformed a barren wasteland into a green park. From a comfort score of 13% in July (due to the heat rebounding from a flat, sandy surface with no shade), this rose to 65% or even 77% with a breeze.

Before and after photos of Parc des Ateliers in Arles. From a barren landscape to a lush green park abounding with biodiversity. Credit: Iwan Baan.

Smets and his team remarked on how quickly animal species returned to the site. Where previously there was no fauna in the area, 36 bird species had returned after the landscape received a makeover.

Thinking locally

Regarding materials, Smets favours rocks and trees. When selecting which materials to use in an urban setting, the landscaper uses local sources where possible. "In Belgium I use a lot of bricks because it’s a typical material we make here with the clay in our soil," he explained.

In Brussels, Smets and his team are currently planning a project on La Jonction, the railroad connecting Brussels Midi and Brussels North station. The tunnel links what is referred to as the high city and the low city and is prone to filling with water when it rains.

Related News

- How Brussels became a frontrunner in sustainable urbanism and architecture

- The Belgian architect combatting climate change

"I would like to use that concrete barrier as an underground dyke to store rainwater and can plant trees," Smets explained. This plays into his vision to demineralise Brussels and bring more greenery into the city.

Tour & Taxis Park, Brussels. Credit: Bureau Bas Smets.

"The historical centre of Brussels is very mineral, meaning it does not have a lot of trees." Smets would like to "take off hardscapes (concrete) to expose the soil which can then store rainwater. This in turn will allow plants to grow, which will cool the environs.

Every leaf counts

When asked if these projects could be realised in cities with smaller budgets than Brussels or Paris, Smets stresses that the size of the project is key: "Creating a green space with some plants is not very expensive, it's breaking existing hardscape that pushes the price up."

Ultimately, Smets believes that "every leaf counts" in the effort to cut CO2.