Walking down Chaussée de Mons in Anderlecht, you might not look twice at the Circularium. Housed in a relic of the past, forged from cold concrete and glass, you have to enter to realise this is something really quite exciting for the city.

Reinterpreting the building’s past, Brussels residents have started something beautiful inside of this brutalist beast.

It is hard to pin down what exactly Circularium is. Our best attempt would be to call it an ecosystem of businesses, community initiatives and local creatives that are coming together to rethink industry and urban economy in a sustainable and circular way.

Passing the grey facade and a charity shop popular among the locals, we venture into the inner courtyard, nicknamed Mons. There we meet Gerd De Wilde, whose organisation MAKETTT (Make it towards transition) runs the place. This man holds the figurative keys of what is arguably the most ambitious urban experiment in Brussels.

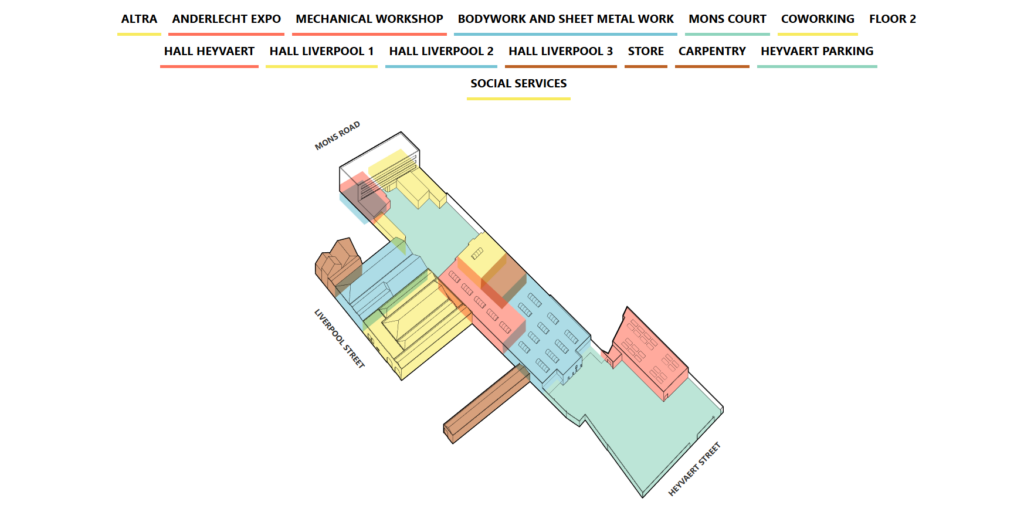

shows every building and businesses occupying them. Credit: Kosmos Khoroshavin / The Brussels Times

“This site has been in operation since the 1950s. It was owned by D’Ieteren, which is one of the oldest Belgian companies. It was a garage, car repair and manufacturing for most of its existence,” says De Wilde.

Once having industry so close to the city centre became a liability, most of D’Ieteren’s activities started gradually moving outside of Brussels and the massive 20,000 m² property became unused. Fast forward to 2020 and MAKETTT took over the place, being hired by D’Ieteren Immo to temporarily make use of the building, which was still in relatively good condition.

“Overall the project has been very well received in the neighbourhood and outside. Since we started around the pandemic it made things easier in a sense that everyone was online, so whatever we launched, it was seen. We had many prominent international guests, including King Phillipe.”

De Wilde's words are confirmed by the fact that the initial five year lifetime of the project was prolonged, giving hope that its scale will expand even further.

Behind closed doors

L'Ilot's furniture stockpile. Credit: Kosmos Khoroshavin / The Brussels Times

De Wilde opens garage doors in front of us, to what looks like a parking space at first glance. But the spaces inside are vast warehouse buildings standing on metallic yellow columns under tall rooves known as “Liverpool halls”. These spaces house facilities for around 10 different organisations.

Many of them are socially oriented, with a heavy emphasis on local community outreach. Gerd walks us through Resto Du Coeur, a collective supplying food boxes for Brussels' most vulnerable people. He points out Rolling Douche, which provides homeless people with hygiene facilities using a mobile camper van and mentions L’Ilot, a bigger organisation who use the space to store furniture given to newly acquired houses for ex-homeless people, free of charge.

Gilbard intern at work. Credit: Kosmos Khoroshavin / The Brussels Times

But the heart of the project is in promoting businesses tied to sustainability and innovation. Hall Liverpool 1 is mostly focused on woodworking. WOW Engineering reuses wooden waste materials, turning them into furniture or structural products, while Gilbard creates art and design projects from local recycled and upcycled materials.

This collective is much more than just a design studio. It's a real community space, which offers workshops to the locals, offering reclaimed wood, metal or paint for “volunteer points” instead of cash or by exchanging your own leftovers.

Their workspace is physically organised in a way to break down the barriers between the neighbourhood and the studio. As Gilbard’s representative explains, “You take off one wall, so that it really becomes an extension of the street.”

Another start-up and a fresh face among different businesses is Adrien Liénard and his Isofabric business. Inspired by examples from the Netherlands and Germany, Liénard produces thermal insulation for houses using textile waste collected by the social economy.

Adrien Liénard standing in one of the Liverpool halls. Credit: Kosmos Khoroshavin / The Brussels Times

Liénard says his goal is to find ways to make much-needed use of Brussels' waste. “Circularium is a great place not just for our stock, but also for the ecosystem," he says "For instance, I discussed the possibility of selling our product with other similar projects here.”

Anywhere you go throughout Circularium, you cannot help but feel raw creative energy and the spirit of entrepreneurship and innovation. Whether its unique foldable Belgian metal constructions from Konligo, furniture for offices and workspaces produced from upcycled wood by Regglo or sustainable metalworking by Fano, the work here never stops.

Microfactory worker. Credit: Kosmos Khoroshavin / The Brussels Times

Joining this circle of sustainable economy entrepreneurs is also quite straightforward. One of the facilities known as 'Microfactory' has around 120 members, who pay a monthly fee to use the space and specialised equipment, which attracts a lot of independent workers looking to save costs.

Walking through there feels almost like visiting a medieval guild. MAKETTT also make sure they use places originally used for metalworking or woodworking for the same purposes in order to capitalise on their original design elements like good ventilation.

Circularium has dozens of fascinating projects in itself, but three specific ventures capture the essence of its spirit. They represent the three pillars of the circular urban economy: manufacturing, sourcing and logistics. Each of these businesses removed the hidden cost of global trade from their projects to show what could be achieved with resources within our reach.

The modern alchemist

Matthieu Meaulle showing off his soaps in his little lab. Credit: Kosmos Khoroshavin / The Brussels Times

Frenchman Matthieu Meaulle is a former economist from the “EU bubble”, who exchanged his office job for one of the rooms of an old garage with his little soap factory inside. “Compared to all of the other soaps, I create mine without products from the other end of the world.”

He explains how he embraces the “cold method” of soap-making that requires more time but results in a product which is better for nature and for the skin. This Brussels soap chemist has even found a way to use rapeseed wax instead of saturated fat for vegan production techniques.

Lungs of the city in your living room

Hugh Roche Kelly at work in Sonian Wood Coop. Credit: Kosmos Khoroshavin / The Brussels Times

Charismatic Irishman Hugh Roche Kelly was inspired by his surroundings in Brussels. The Sonian Forest produces massive amounts of high-quality beech wood, but this local resource was long treated as a raw commodity for export.

"Up until we came along, the vast majority of that material was being sold in the open market and basically being shipped to low-cost sawmills in Asia... and then reimported back into Europe as European beech," Hugh says. "We wanted to intervene in that slightly nonsensical approach," he says.

Today his Sonian Wood Co-op turns trees felled by storms or cut by forest managers into high-end tables and cladding just a few kilometres from where they grew.

Brussels City Movers

Brussels team leader Baptistine and courier working for Cargo velo. Credit: Kosmos Khoroshavin / The Brussels Times

Connecting producers to the city is the job of Cargo Velo and their Brussels’ team leader Baptistine with theirfleet of heavy-duty cargo bikes capable of hauling up to 100 kilograms. They specialise in “last mile” transportion, replacing vans that clog the streets of Brussels.

The Bike messenger concept became popular in New York, specialising in mail, but Cargo Velo carries anything from medicine samples and coffee to furniture.

Perhaps the best part about this business is its rejection of the exploitative gig work that most bike delivery drivers face.

"We are following the rules of logistic transport, so we are considered like truck drivers," Baptistine explains. "That is what costs us the most, everyone has a real contract. If we decided to pay people by delivery it would be more sustainable financially, but it would not be ethical."